Remembering When Women Ruled a Wild West Town

In 1920 the “bad-man rendezvous” of Jackson, Wyoming, elected an all-female government. Will it be another hundred years till that happens again?

Picture, for a moment, Kamala Harris cleaning up a territory known for horse thieves and train bandits, Elizabeth Warren boosting the treasury tenfold, and Amy Klobuchar squaring off against her own husband in an election. Now imagine all these women running on a ticket together, throw in two more of your favorite female politicos, then pop the bubbly (or mountain moonshine) for their blowout victory.

That’s essentially what happened, on a much smaller scale, a century ago in Jackson, Wyoming. The 2020 presidential election may have given us an unprecedented number of female candidates—six in the Democratic primary—but 1920 yielded one of America’s earliest female-run governments.

This spring marks the 100th anniversary of the election of the “petticoat rulers,” the name given to the ladies who took over Jackson, the notoriously lawless town. On May 11, 1920, the all-female ticket—with Grace Miller as mayor and Rose Crabtree, Mae Deloney, Faustina Haight, and Genevieve Van Vleck as council members—claimed victory against an all-male roster. The election drew the most voters the town had seen at that point (Jackson was incorporated in 1914), and in many cases, the women bested their opposite-gender opponents by 2-to-1. Rose Crabtree even toppled her husband, Henry, to claim her spot on the council.

“Of course they knew the significance of the moment on some level,” says Jim Rooks, great-grandson of Genevieve Van Vleck and a high-school social-studies teacher in Jackson today. “But I don’t think they ever could’ve fathomed that 100 years later people would still be celebrating the event.”

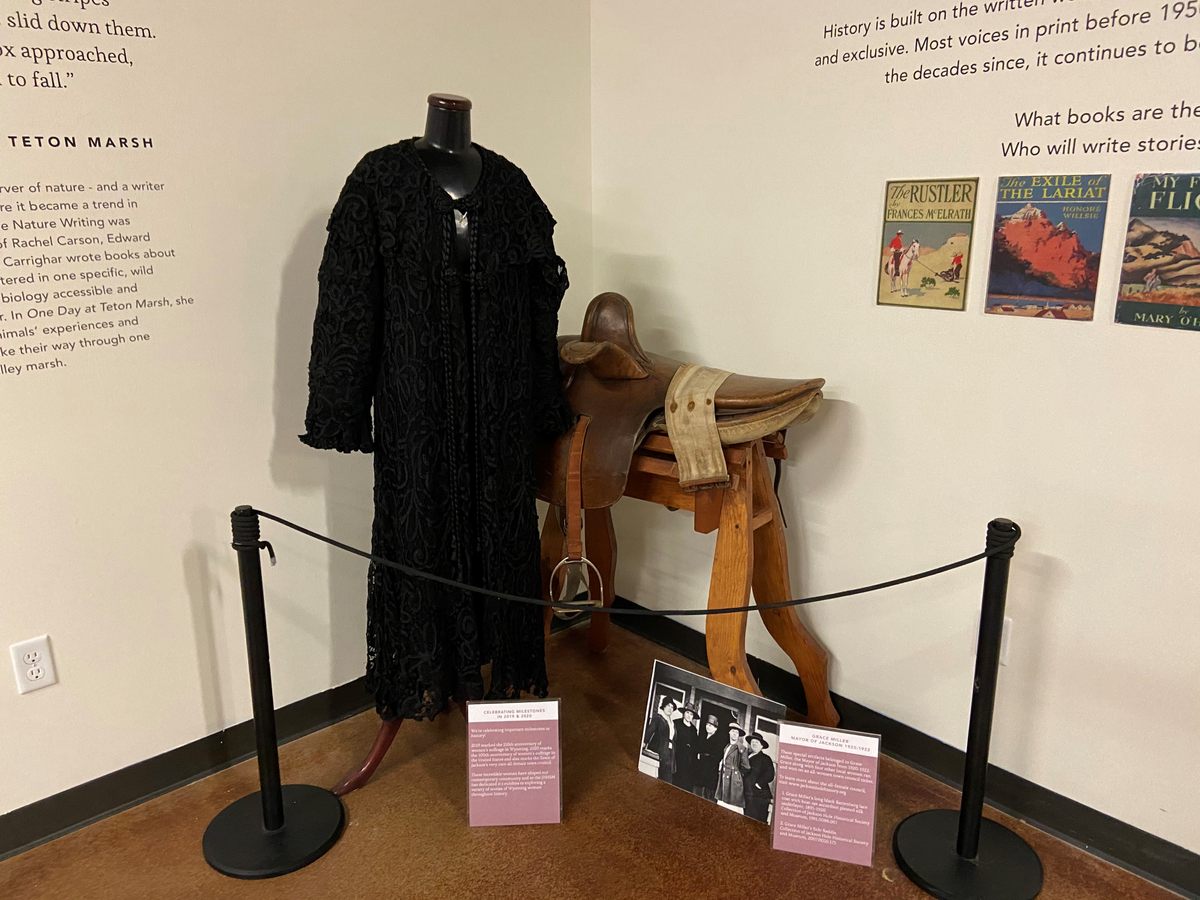

“It’s a story that Jackson is really proud of and has been telling since the women were elected,” says Morgan Jaouen, executive director of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Once the museum reopens this summer—it’s been closed since March 16 due to coronavirus—Miller’s jacket and side saddle will be on display as part of an exhibit called “Mountains to Manuscripts,” which highlights Wyoming’s rich history of female writers.

(Jaouen assembled a petticoat curatorial crew herself, enlisting only women to work on the project. It was set to close this spring but will likely remain in place through March 2021—something of a silver lining caused by coronavirus reshuffling).

The petticoat story still inspires local pride, but back in 1920, news of a lady-led government made waves from coast to coast. The New York Evening Herald ran the headline “Women Rule Western City; Gun Play Thru,” while the Los Angeles Times reported “Woman Mayor Running Former Bad-Man Rendezvous.” As far away as London, The Daily Chronicle trumpeted a “Town Ruled by Women. Would-Be Counciller [sic] Defeated by His Own Wife.” (For the record, Henry Crabtree is said to have taken his defeat in stride.)

The general consensus among newspapers at the time was that with women in power, Jackson would no longer enable a kind of Wild West criminality the area was known for: bands of horse thieves, fatal barroom brawls, gold miner murders. Though most of its citizens were law abiding, the town of Jackson, which is the center of Jackson Hole valley, had a reputation for being an outlaw refuge, thanks to its isolated mountain setting.

Jackson’s Hole Courier put it this way in 1920: “Whenever a serious crime was committed between the Mississippi River and the Pacific coast, it was pretty safe to guess that the man responsible for it was either headed for Jackson’s Hole or already had reached it.”

Even if purported gun play was “thru,” at least one bandit from the crime-riddled region didn’t seem to mind. When the women went on to win a second term a year later—this time by a 3-to-1 margin—Ed Trafton, a convicted stagecoach robber fresh from prison, sent a congratulatory letter to Miller. “I believe your little city has the distinction of being the first in the U.S. to elect its city government of women,” he wrote. “It not only shows the confidence placed in its intelligent women, but the progressive intelligence of its citizens. Hurrah for Jackson, WY.”

Actually, Grace Miller’s group wasn’t the country’s first all-female town council; Oskaloosa, Kansas, elected one in 1888, and Kanab, Utah, welcomed its own in 1912. But Jackson’s was perhaps the most famous.

That’s in large part due to timing: Ladies in politics was big news in 1920, the year the 19th Amendment was ratified and women across the country finally won the right to vote. (Wyoming had actually granted suffrage over 50 years earlier, in 1869—the first state to do so, thereby earning the nickname the Equality State.)

Jackson’s all-female town council was also exemplary in appointing only women to fill remaining government roles. Marta Winger became the town clerk, Edna Huff the health officer, and Viola Lunbeck the treasurer, while Pearl Williams—a five-foot-tall, 22-year-old dynamo—nabbed the position of marshal.

“She says that a while ago, she killed three men and buried them herself and that she hasn’t had no trouble with anybody since,” reported Jackson’s Hole Courier in May 1921 of Williams’ time as marshal.

In reality, Williams, whose pre-marshal résumé included only one job (soda squirt), spent most of her time keeping swine and cattle out of the town square. “I had a horse, so [the all-women council] thought I could keep the cows out of town,” Williams (who became Hupp by marriage) told her nephew in a 1983 interview. The rest she played up for the papers, though she did occasionally have a prisoner in her one-room jail.

What wasn’t exaggerated was the effectiveness of Mayor Miller’s government over the course of its three-year tenure. Within a fortnight, the women raised the town coffers from $200 to $2,000 by rounding up money due (the previous male leaders hadn’t bothered to actually collect taxes). They created a more concrete town square by grading the surrounding streets and installing electric lights. Mindful that Jackson needed a proper place to mourn, the ladies (all described as “councilmen” in the official minutes) bought the title to a 40-acre plot that became Aspen Hill Cemetery and built a road leading to the graveyard. They also instituted a bit of civility by prohibiting cattle grazing in public areas (thanks, of course, to the help of Williams), as well as the launching of firecrackers and other explosives.

“I remember my grandma describing her mother’s, Genevieve’s, expression that they needed to ‘settle up this place,’” says Rooks, explaining that the phrase comes from homesteading. “If you got a homestead, you had to settle it up; you had to improve it.”

This pragmatism may help explain how the women took over Jackson in the first place. “There was a practical approach to it: We need this, and we’ll do it ourselves,” says Michelle Rooks, another Van Vleck descendant (and Jim’s sister).

And yet, despite proof of petticoat success, Grace Miller’s government didn’t exactly set a precedent. Jaouen points out that Jackson didn’t have another female council member until the 1980s. Nor did the town elect another female mayor until 2001, when Jeanne Jackson became the executive. Sara Flitner, elected for a two-year term in 2014, was Jackson’s only other woman mayor.

“I do think [the petticoat rulers are] an inspirational story for young girls and for women,” says Jaouen. “But it did not set a standard or a path forward to where this became normal and accepted. I think women still have to work really hard to be in positions of leadership and power.”

Wyoming as a whole has had a tough time with gender representation in recent years. According to the Center for American Women and Politics, when it comes to women serving in the state legislature, the Equality State ranks 48th.

As for why the political gains of the 1920s didn’t continue to build, Jaouen says you have to do a deeper dive into why the petticoat rulers were elected in the first place. The answer, she says, is quite nuanced. Rather than a sweeping call to feminism, the all-women government was born of circumstance. Even though they ran against men, the women were elected to do a job that wasn’t particularly popular at the time.

“People were focused on other things, like farming and just trying to make a living,” says Jaouen. “They didn’t necessarily have time for civic duty.”

Statewide, experts theorize that women’s diminished role in politics over the last century is due in part to Wyoming’s shift from pioneering territory to settled state. When Grace Miller’s group took office, homesteading, which would last until 1927, was still a viable way to earn land. During that period, male attention was focused elsewhere, away from government roles. That’s, of course, in addition to blatant sexism and a belief that women shouldn’t lead.

Like Jaouen, Michelle Rooks struggles to reconcile what happened in 1920 with the century that followed. “Sometimes I discount what this meant,” Michelle says of the petticoat government. “And you know, maybe they weren’t politically motivated, but think about what it means.” But she quickly follows up her marveling with a question: “That happened 100 years ago, and we still have only had two female mayors following that … what’s that all about?”

While petticoat rule feels like a flash in the pan, ghosts of the all-woman government remain in Jackson today. Grace Miller’s ranch still stands and is part of the National Elk Refuge. Genevieve Van Vleck’s former home has become a restaurant, Café Genevieve. And a replica of the hotel that Rose and Henry Crabtree owned is now a retail space called Crabtree Corner (look for the Häagen-Dazs).

Additionally, a locally iconic photo of the 1920 town council, snapped on Van Vleck’s front porch, hangs in bars, restaurants, and grocery stores around town.

In the grand scheme of American politics, the 100th anniversary of the petticoat rulers is a reminder that momentum is never guaranteed—a lesson to keep in mind as we come off our most diverse presidential primary in history. And on a smaller scale, the story of Grace Miller and her lady gang illustrates how female-pioneered pragmatism helped tame a disorderly mountain town. It’s a legend in how the West was won—by women.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook