How to Write an Opera About Locusts

In Wyoming, a buzzworthy bug mystery hits the stage.

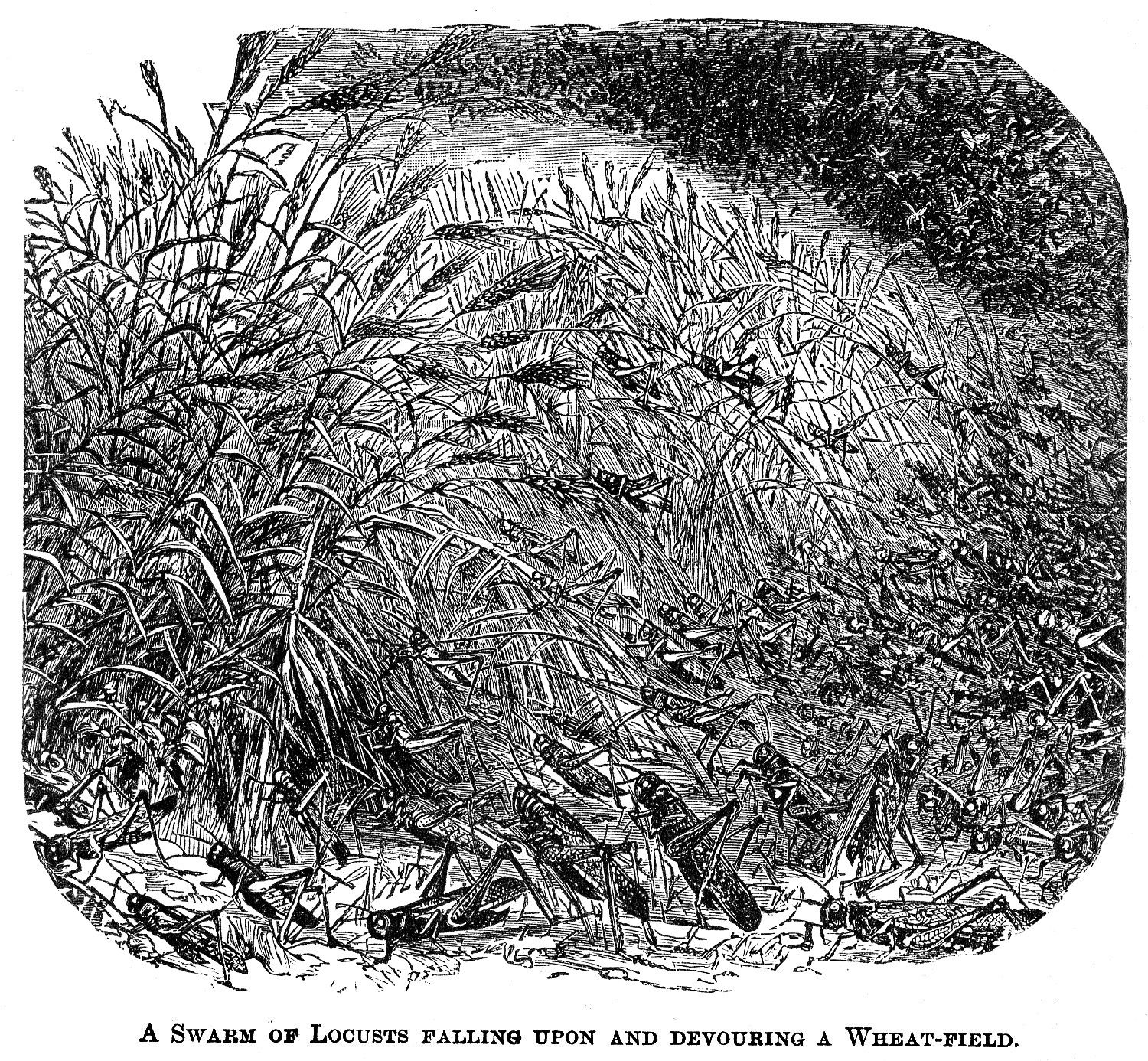

The Rocky Mountain locust once ran the American West. For decades, it swarmed the United States from Minnesota to the coast, eating pioneers out of house and home. One legendary gathering, of perhaps 3.5 trillion insects, is thought to be the largest concentration of animals in recorded history. It was “an earnest and overwhelming visitation,” one spectator wrote at the time. “[They] demonstrated with an amazing rapidity that their appetite was voracious, and that everything green belonged to them for their sustenance.”

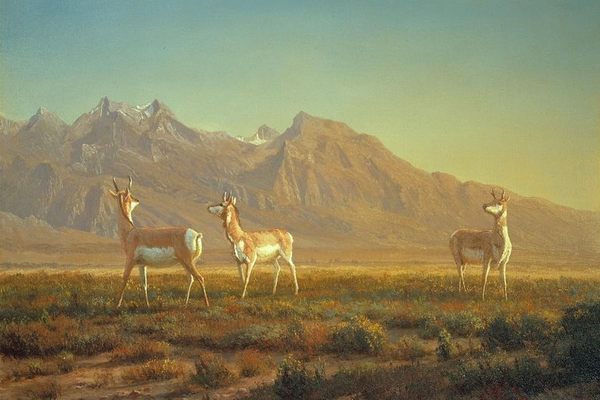

Then, around the turn of the century, the species vanished. The last one was seen alive in 1902. “The locust caused terrible human suffering, but then we lost this iconic creature,” says Jeffrey Lockwood, an entomologist at the University of Wyoming. “It was a species that defined the Western landscape.”

This past weekend, the long-lost bug briefly showed up somewhere unexpected: onstage, singing, and wearing a sparkling dress. Locust: The Opera premiered on September 28, 2018, at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. Through arias and recitatives, it tells the tale of the Rocky Mountain locust—what it was, why it disappeared, and what we can still learn from its story.

Lockwood began studying the Rocky Mountain locust about 30 years ago, when he first moved to Wyoming. While people had proposed various reasons for the creature’s downfall, he says, none of them quite added up, and solving the mystery “became a fascination.” He trawled through old accounts of locusts blotting out the skies. He traveled to some of the various glaciers where the bugs are preserved, exhuming frozen individuals to test out different hypotheses.

In 2000, he published a book laying out his own theory. Like many insects, locusts have uneven population cycles. During boom times, they ranged all over the West. But in leaner years, the swarms “collapsed back into the well-drained, fertile, sandy river valleys of the Rockies,” Lockwood says. “That was sort of its sanctuary.” Pioneers, of course, were drawn to the exact same places. They plowed fields, chopped down trees, and rerouted rivers. “There was wholesale habitat destruction,” he says. “The entire system collapsed.”

Lockwood was happy to have arrived at a more robust theory. But the insect wasn’t done with him yet. “I’ve come over the years to enjoy opera,” he says. “The story of the Rocky Mountain locust had this epic scale, of time and place and drama, that lent itself to an operatic treatment.” So he decided to write a libretto.

As he had never done this before, he approached the task scientifically, calculating the average number of words per minute for several of his favorite operas, and using that as a guide. He ended up with three characters: a scientist, a rancher, and the ghost of the Rocky Mountain locust. “She is haunting the scientist until he can come up with an explanation for how her [species] was killed,” he says.

When he was done, he took it to another University of Wyoming professor, the composer Anne Guzzo. “If you think about a giant swarm of locusts, a bunch of bugs, it’s kind of icky,” she says. “They eat everything. It could be this gross thing, or terrifying.” Instead, she decided to think of the locust’s story as a tragedy. “I took her music, and I tried to make it the most beautiful, sparkling, gorgeous thing I could do,” she says. (The locust was played by the soprano Cristin Colvin, who told the University of Wyoming press office that she was “thrilled to perform a role in which I am not purely human, but a dream figure.”)

For the scientist’s parts, Guzzo skewed more modern, getting across his mindset with “interrupted phrases, and jumpy music.” The rancher, she says, is “not as convoluted and as stuck in his head as the scientist. He gets a more earthy sound.” The audience was tasked with playing the swarm, by rustling pieces of tissue paper from their seats.

The premiere was well-received. (It “made perfect sense,” wrote the critic Richard Anderson, who also pointed out that the story involved “more death than all the rest of the operatic repertoire put together.”) This particular run was short—it only lasted the weekend—but Locust: The Opera will be performed at least one more time, in March 2019, at the 13th International Congress of Orthopterology in Morocco. Its creators are also seeking funding to bring it elsewhere.

Even after all of this, the story of the Rocky Mountain locust hasn’t quite let go of Lockwood. It might be because this bug resembles another animal, equally voracious and equally fragile. “Our species is highly mobile, profligate, and abundant,” he points out. “So is the locust. One of the lessons is, being abundant doesn’t ensure survival.” We can only hope that someday, the cockroaches write an opera about us.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook