Where Damaged Art Goes When It’s Deemed a ‘Total Loss’

A second life for wrecked artworks that once languished in insurance warehouses.

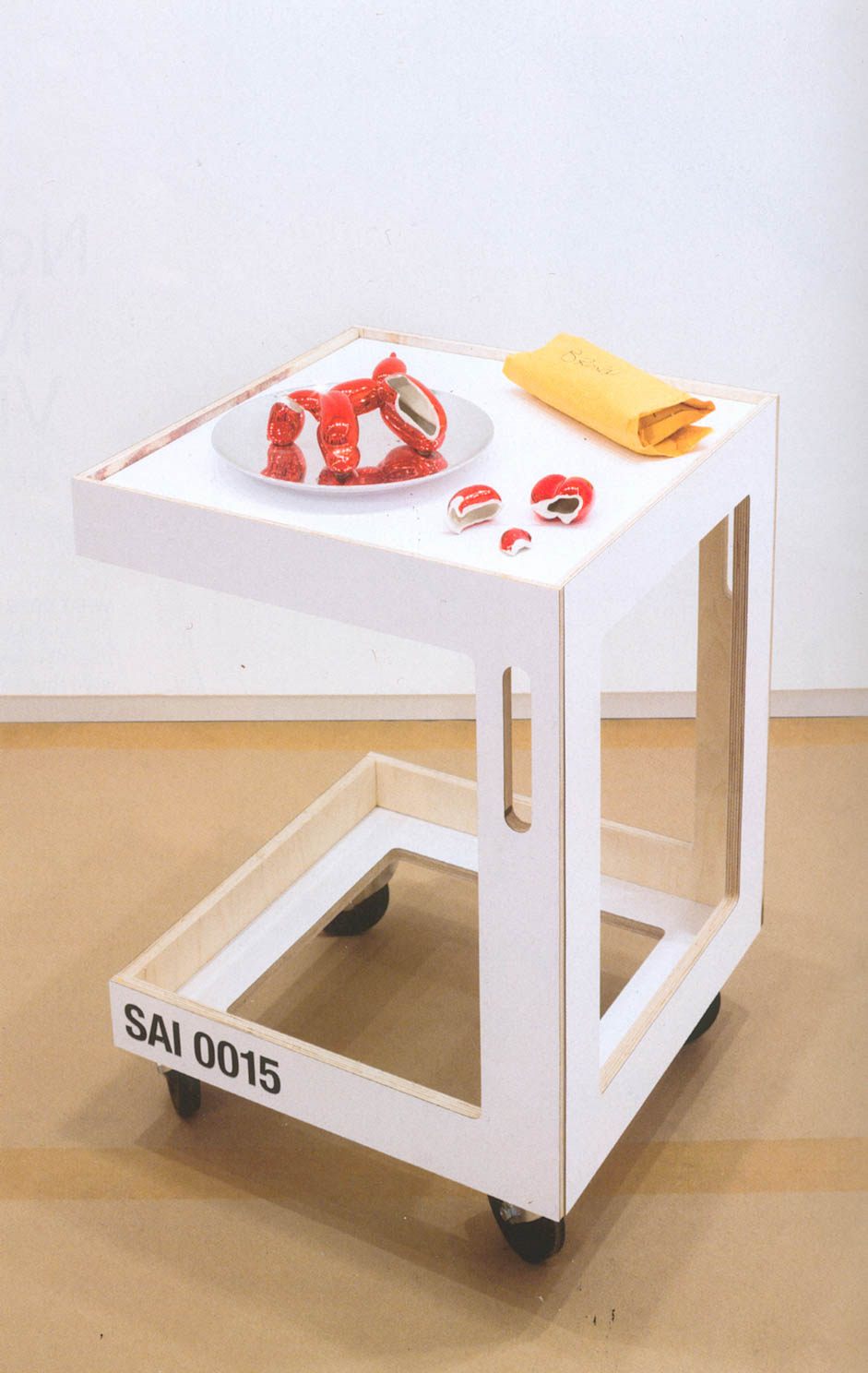

After someone accidentally dropped Jeff Koons’s Red Balloon Dog in 2008, the fractured porcelain sculpture was considered damaged beyond repair. Similar works by Koons have been valued at tens of thousands of dollars, but after an art insurer ran a total-loss claim on the piece, Red Balloon Dog was, legally, worth nothing at all.

Koons’s broken sculpture is, however, worth something to Polish artist Elka Krajewska, founder of the Salvage Art Institute, which actively collects pieces that have been declared a total loss, and promotes conversations around them. Red Balloon Dog is now part of a rotating inventory of damaged artwork given new life in Krajewska’s traveling exhibition.

In many ways, art insurance is a lot like car insurance. When the cost to fix a damaged piece (or car) exceeds its perceived worth, or the damage is considered too extensive, the work goes through a total-loss claim. The value of the piece officially becomes zero, and it’s declared “salvage art” by insurers. Some of these salvage works end up on the walls of art insurance offices the world over, but more often they’re stored in warehouses, in a kind of limbo while the insurer figures out if they can be auctioned to make up for some of the paid-out claim.

Hearing about these mausoleum-like warehouses for art was a revelation for Krajewska. During a conversation with her neighbor, who at the time did public relations for the art insurance company AXA Art, Krajewska came up with the idea of creating an institute that would give new life to the forgotten salvage art inventory. When she brought her idea to AXA Art, CEO Christiane Fischer told her she’d been thinking about what to do with total-loss works all her professional life.

The Salvage Art Institute (SAI) was founded in 2009 in New York City, and a few years later AXA Art donated the first 40 pieces to the institute, along with—just as importantly—the corresponding paperwork documenting the art’s journey from market to being declared a loss. Since then, the collection has existed as a traveling exhibit with a rotating display of around 50 works. It was last exhibited in Warsaw in 2016, and preparations are underway for a show in Munich.

Each exhibit includes SAI’s policies in a large block of text on the wall. “SAI is a haven for all art officially declared as total loss, removed from art market circulation,” it reads. SAI dubs these objects, freed from the constraints of the art market, “No Longer Art.” But for Krajewska, it’s not the destruction of a piece that’s important, but the evolving narrative that goes along with suddenly becoming valueless. The legal designation becomes a new chapter in an artwork’s story, and informs how we experience it. Krawjeska feels that a new kind of value—free from markets—emerges from legal worthlessness.

Each object’s narrative begins in more or less the same way. A work is created and declared art by way of the artist’s signature. It is exhibited in a museum or displayed in a private collection. But it’s here where each story spins out in a different direction. Some pieces are damaged during shipping, or by leaking water, or mold. Krajewska says a new signature, this time the insurance adjuster’s, “marks the severance of the work from the artist.”

Documents with notes such as “suffered a long L-shaped tear on the proper left side,” “mold grew all along the bottom edge,” and “the head had become detached from the base” are displayed alongside the objects at SAI exhibits. The tone remains as neutral as possible, and maintains the legal frame to the art’s demise.

SAI comments on the storytelling power of this documentation in its book about the project, No Longer Art: A Narrative. It reads, “at times bursts of feeling and character broke through … scribbles and cross-outs, exclamation points, celebratory language, personal addresses.… There was not just legal formality here, but narrative structure.”

One object among SAI’s rotating inventory is a massive two-panel drawing, Untitled (Prayer), made with graphite and gunpowder by American artist Linda Bond. The black-and-white imagery was damaged by a water leak in 2007. And one of the panels suffered additional, rather poetic, harm: “An unsupervised child entered the unattended gallery and drew his hand across the entire length of the ten foot drawing.”

After settling with the insurance company, Bond, like many artists dealing with damaged works, just wanted to move on. But, she says, she “was delighted that the work—although damaged—had a second life.”

SAI’s mission is to not just give these works a second life, but to promote a dialogue about the way we ascribe value in the art world. Preserving salvage art effectively inverts the typical aim of the art market, which only deems works with financial value worth protecting. Krajewska believes young people are “hungry for reassessments of their belief systems, and deprived of dreaming because of economics and extreme competition in the art world.” A conversation about “No Longer Art” is one way to break through stale old conventions.

Now, along with the rest of the damaged works at SAI, people are welcome to touch Bond’s drawing. Most find it a thrilling experience, to engage with objects once entirely off-limits to any kind of tactile interaction. Often, after handling Bond’s drawing, visitors touch other objects, and leave gunpowder fingerprints all over the place. Where, it all suggests, does art begin and end?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook