The Quest to Find the Lost Column of Venice

Led by a pipe-smoking Venetian diver, an eclectic team is searching for a legendary monument.

When the captain came home to the waters of Venice, he returned to a republic on the rise. Independent and ruled by the doge, this city-state of islands dominated Europe’s trade with the Levant* and throughout the Byzantine Empire. Its ships sailed off to the Crusades and came home laden with art and other riches. Venice was only beginning to imagine the place it could hold in the world.

This was sometime in the 12th or 13th century, and the captain was returning from the east: Constantinople, perhaps, or Tyre in Lebanon. He had a gift for the doge. On his ship were three granite columns, it is said, each two stories tall—marvels of conquest, a new glory for Venice.

The captain sailed into the main harbor and, anchored in front of the doge’s palace, ordered the columns moved ashore. But the weather turned, and one of them slipped from the sailors’ control. It sank and was never seen again.

Hundreds of years later, two of those great columns stand in the Piazza San Marco, the central and most visited square in Venice. Sometimes called the Columns of Justice, they flank the piazza’s entrance from the harbor. Topped with statues representing San Todaro and San Marco, the city’s patron saints, the columns are solid and real, each an enduring symbol of Venetian might and wealth. The third, lost column is a legend that has been repeated for hundreds of years, and has worked its way into histories and guidebooks—with no proof of that it had ever been there.

But another Venetian captain believes the third column could be real. For the past three years, Roberto Padoan—Capitan Pipa, he likes to be called, for his Popeye-esque pipe habit—has been planning a new search for the long-lost treasure, a quest he has named the Aurora Project. He has assembled a crew of archaeologists, geophysicists, artists, filmmakers, and engineers, and soon they are going to look deep under the most famous place in Venice for a pillar of granite that may or may not exist.

“Of course mediocre people will tell you that it’s just a legend without even trying to find it,” Padoan says. “But we don’t have any written evidence of the other two columns, either. Yet they have been standing there for centuries.”

Padoan was 10 years old when he discovered his hero, legendary French documentarian Jacques Cousteau. Every Wednesday he stayed up late to watch Cousteau on television, he told a crowd gathered at Ateneo Veneto, one of Venice’s most prominent cultural institutions, in January. That night, the bearded Padoan wore his usual outfit—a navy turtleneck and a basque hat. “I am a man of the sea,” he says proudly. “Even when everyone is wearing a tie, I would wear my turtleneck because that’s who I am.”

Just like his childhood hero, Padoan spent most of his life in the ocean, working as a superyacht captain in the Mediterranean and an underwater surveyor in Venice’s murky lagoon. “I know the Mediterranean sea well above the water,” he says. “But I know Venice mostly underwater.”

It was during these hour-long dives in the muddy waters of La Serenissima, where it can be impossible to see an inch ahead, that he grew impatient with the lagoon’s condition. “I wanted to find a way to make water clearer,” he says. In 2001, he invented a technology, which he calls ACLA or Acqua Chiara Laguna Azzurra, which he says can filter particles and microorganisms from a section of water about 11 feet wide—without chemicals. He tried it under the Bridge of Freedom, which connects Venice to the mainland, and says that he found visibility greatly improved. Two other local underwater conservation projects, at Dona Bridge and San Pietro di Castello, a basilica that stands on underwater stilts, have also used the technology.

Since then, Padoan has tinkered with other underwater inventions, as he likes to call them, including a waterproof resin that can be applied to strengthen the wooden piles under most of Venice’s buildings. But it was not until three years ago that he started to wonder if his visibility technology could be used for another purpose.

“They say the third column of Venice is a legend, but legends are half true,” the captain says. “So I started to wonder what’s real and what’s not about this.”

Padoan, who was born and raised in the center of Venice, feels a strong sense of belonging there, and for him the lost column symbolizes the city’s beauty and strength. He’s not bothered by the lack of any textual evidence. “Ever since I was a kid I wanted to do something like Cousteau,” he says. “He trusted his intuition to look for what’s hidden. I want to do the same for Venice.”

From the beginning of its rise, Venice was built on imports. The city’s original patron saint was San Todaro, until the 820s, when two Venetian merchants brought the relics of San Marco home with them from Alexandria—after which it had two patron saints, one imported. (In some versions of the story, the merchants stole the saint’s bones. In others, they rescue the relics from the threat of plunder by enemies of Christianity.)

As Venice’s wealth increased, the church that still houses the relics, and the piazza in front of it, grew in splendor. “There’s nothing comparable in Venice,” says art historian Robert Nelson, co-editor of the book San Marco, Byzantium, and the Myths of Venice. The piazza, he notes, is a “very large public space in a city where the space is at an extreme premium.”

Venice, from the sea, does not look impressive. Built on a collection of small, low-lying islands spread across a mudflat at the northernmost point of the Mediterranean, the city was, however, ideally located to move goods from the sea to Germany and Central Europe. It had little going for it besides its location, and no Roman or Etruscan past to build on. “Everything had to be brought in,” says Nelson. “Venice had nothing, yet it tried to compete with the other empires of the Mediterranean. It needed history in order to make itself great. It invented traditions all over the place.”

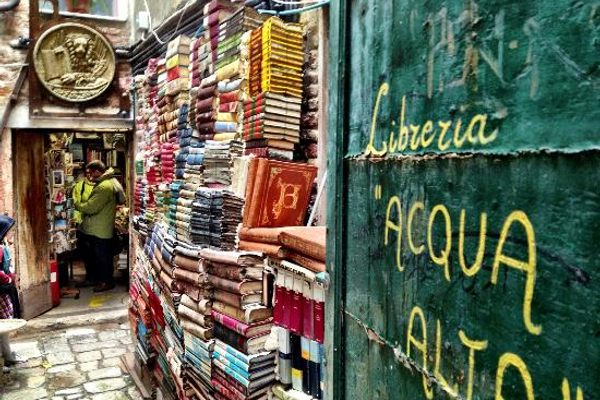

Decorated with the lifted riches of other places, the Piazza San Marco is representative of this rise. The facade of the church of San Marco is a collection of Byzantine art. At one point, Venetian ships were under orders from the government to bring marble columns back from their voyages. The Columns of Justice greeted foreign dignitaries and framed their first view of the city. Their foundations are made of Croatian stone, their capitals of Veronese marble. “Everything is a collage,” says Nicola Baratto, an independent researcher and artist who has been working with Padoan on the Aurora Project.

Baratto joined Padoan’s team because he was intrigued by the lost column’s myth, and he has been trying to understand how the legend fits into Venice’s history. “The whole story is covered by a veil of uncertainty,” he says. The columns might have come to Venice as early as 1122, though many experts now put their arrival at 1268. By 1487, the date of the earliest written reference Baratto has found to the third column, the story was already ensconced in Venetian lore, and historians were debating where the columns had originally come from. While one of the existing columns is made from Turkish stone and the other of red Egyptian stone, the similar craftsmanship suggests they came from the same place, with Constantinople as a leading contender.

“There is no real historical nor scientific proof or evidence for the existence of the third column,” Baratto says. “But seeing the two gives legitimacy to the dream of the third.” The third gives the story an archetypal quality: a captain returns from the East with a monumental trinity.

All over the Mediterranean, stories accrue around antiquities. But Venice, unanchored in the classical world, has a penchant for reshaping its own mythos. “Reading the present into the past or the past into the present is a well-established practice in Venice, especially for artifacts in prominent locations,” Nelson, the art historian, writes. The Venice of today—sinking into the mud, threatened by rising seas, overrun by tourists—can seem like a simulacrum of what it once was. A lost column is reminder of the city’s mystery and power, from the beginning of its rise to prominence. “Speaking about a fundamental quest, searching for something that is invisible and unknown—it is a strategy or a way to face the future,” say Baratto.

Or, as Capitan Pipa says, “The column is much more than an object. It’s a symbol of the beauty and strength of Venice.”

To begin the search for the lost column, Padoan and his team must first navigate a labyrinthine bureaucracy to allow them to essentially take over part of one of the most touristed sites in the world. The plan is to examine parts of the foundations of the piazza and waters just beyond, using both tomographic analysis, which will scan the ground down to a depth of around 35 feet, and Padoan’s water-clearing technology. Baratto and his colleagues on the communications side of the project are planning a pavillion that will create a private space for the geophysicists, engineers, and archaeologists to do their work, as well as communicate the story of the lost column to the public.

To some extent, discovering the column itself is not critical to the success of the larger project. “If we do end up finding something that’s good, but even if we don’t find anything, that works as well,” says Marco Bortoletto, one of the archaeologists on the team. Previous excavations have examined the world under the piazza, Bortoletto says, but some of the most interesting areas have gone unexplored. Using the geophysical technology, they’ll be able to see further into the history of this iconic place.

Padoan believes that a trove of archaeological treasures currently lie in the muddy waters under and around the piazza, and is hoping to livestream the exploration in real time. “Imagine what must be down there,” he says. “The column is just the tip of the iceberg.”

This story was inspired by Atlas Obscura’s 2017 trip to Venice. Travel with us to discover more untold stories about the world’s most fascinating places.

*Correction: This article was updated to change the “Levantine Peninsula” to the “Levant.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook