How Sears and Montgomery Ward Changed American Shipping

In the 19th century, if you wanted a package delivered and you didn’t live in a big city, you were pretty much out of luck.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Package delivery is a well-tread art at this point, and one that didn’t come to life on its own.

But decades ago, long before Amazon Prime and same-day fish delivery services, when the American shipping industry was still in its infancy, it was similar, if wholly different kinds of companies that helped shepherd home delivery into adolescence: mail-order catalogs, from Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, namely, two shops you might have heard of.

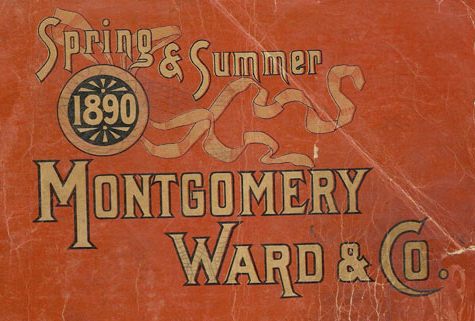

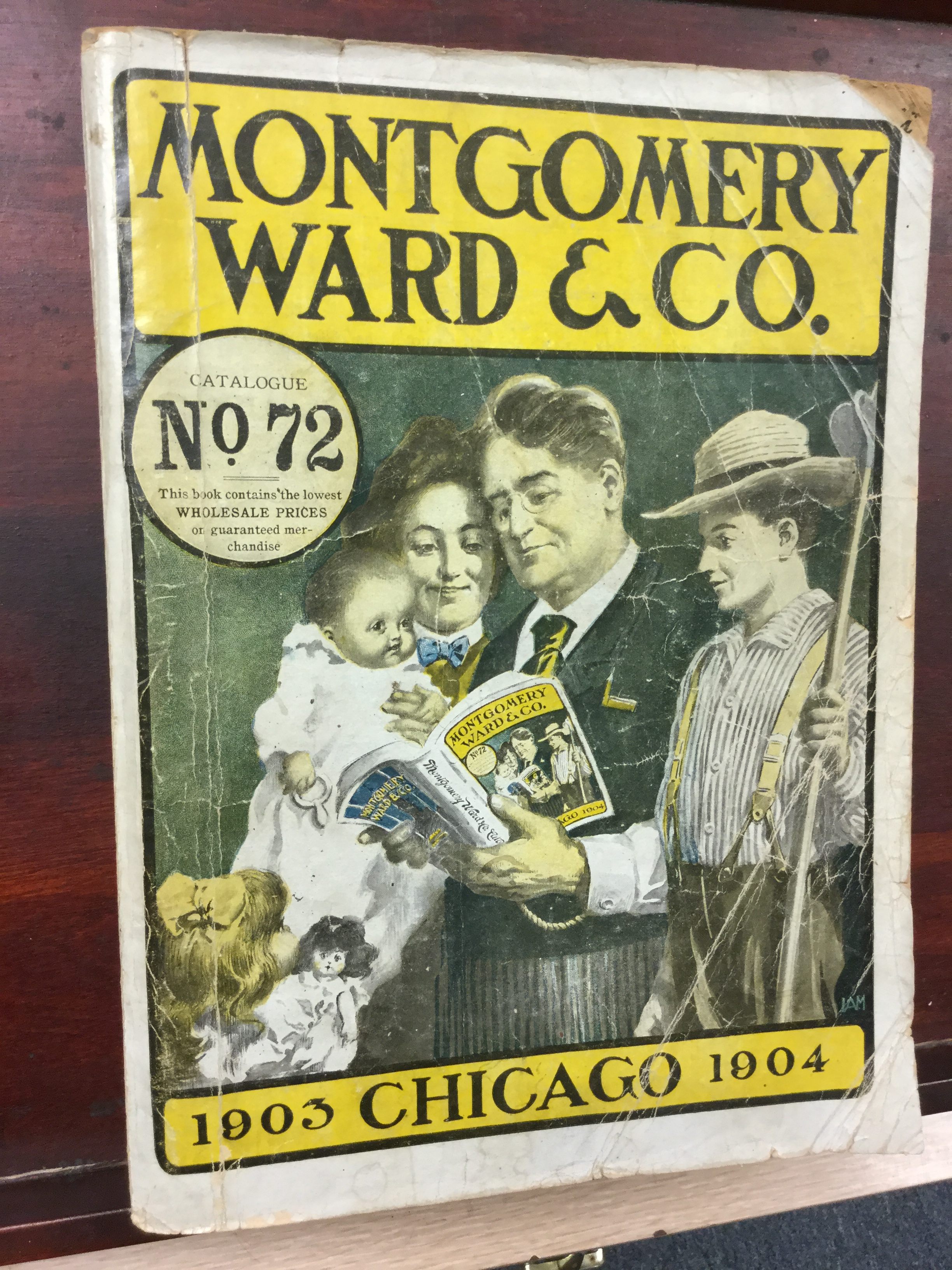

Both companies’ catalogs, each debuting in the late 19th century, successfully capitalized on the expansion of the country’s mail and package delivery systems, in particular the novel service of postal delivery to rural addresses. They also coincided with the rise of the American shipping industry, beginning a symbiotic relationship that persists with giants like Amazon today.

Aaron Montgomery Ward, who founded his namesake company in 1872, was the first out of the gate, setting the stage for the mail-order business by delivering products through the budding rail system. As long as you could get to the closest rail station to pick it up, the idea went, Montgomery Ward could help you save a few bucks and get a better selection than the nearby general store—though that move wasn’t obvious right off the bat.

“The original plan of conducting our business, suggested by the growing combination of farmers to deal directly with a house near the base of supplies, was to ship goods by Express, collect on delivery (i.e. C.O.D.) only,” the company explained in a 1875 catalog, “But as time passed and strangers became friends, the necessity of reducing the expenses of transportation became apparent, and we allowed goods to go by Freight to Granges, when the Grange seal was affixed to the order.”

(“Grange,” by the way, refers to the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, a major fraternal organization representing farmers. Its influence, highlighted by its mark on the shipments sent via the rail system, was key to both the success of mail-order houses like Montgomery Ward and the later success of the rural mail system.)

Ward’s business succeeded, despite the fact that he had an early setback after his inventory was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

While Montgomery Ward was growing, a rail employee elsewhere was learning the system from the inside. From his early vantage point at a rail station in North Redwood, Minnesota, Richard W. Sears noticed that wholesalers sometimes had more supply than demand for their products, and took advantage of this at one point by buying a number of watches from a wholesaler below cost, then selling them at a tidy profit. It would soon become an important way for Sears to fill its eventual catalogs.

Sears and his colleague, watchmaker Alvah C. Roebuck, eventually moved far beyond watches, and, by the 1890s, Sears was beginning to outpace Montgomery Ward. Still, both were sizable at this point—and were about to become even bigger, thanks to the federal government at the time.

The biggest problem that mail-order catalogs faced at the turn of the 20th century was the fact that their intended audience—often rural, as that was 65 percent of the U.S. population at the time—didn’t have easy access to mail delivery. Outside of cities, the infrastructure just wasn’t there, and often people had to pay just to get someone to simply deliver their mail to them—let alone parcels, which the U.S. Postal Service didn’t handle at the time.

The solution to this problem was something called rural free delivery, which was heavily pushed by farmers’ advocacy groups. Despite the growing desire to create mail delivery in rural areas, there was much pushback on the issue within Congress due to the high cost, and as a result, the idea only came about in baby steps before finally rolling out wide in 1902.

And with that, mail-order businesses like Sears and Montgomery Ward could now get their catalogs to people around the country.

But it wasn’t an automatic change, of course. This need to get mail to rural areas was a major driver behind infrastructure building, leading to the creation of roads, eventually allowing cars to drive on those roads to deliver mail. Things improved enough that, by 1913, the U.S. Post Office itself was delivering domestic post packages.

Parcel post, which both Sears and Montgomery Ward lobbied heavily for, didn’t come overnight, however. Traditional retailers fought the catalog giants on the issue in the political realm, which was part of the reason why domestic parcels came about 26 full years after foreign ones did. But once they did get off the ground, they helped redefine the companies’ respective businesses. In the first year the service was available, Sears’ sales increased fivefold, and its revenues soon surged.

The commercial machine of home delivery continues to alter the way shipping services and the U.S. Postal Service do business, of course.

More than a century after Sears made his discovery about wholesalers, for example, a businessman who had spent time on Wall Street and dabbled in internet-based technology traveled across the country, inspired by a Supreme Court ruling that changed the parameters of interstate commerce. Simply, the 1992 case Quill Corp. v. North Dakota set the rules so that businesses with no physical presence in a state were not required to collect taxes on sales they made.

That man was Jeff Bezos, and his business, Amazon, grew quickly thanks to that loophole. Now, Amazon is so big that it gets the U.S. Postal Service to deliver on Sundays.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook