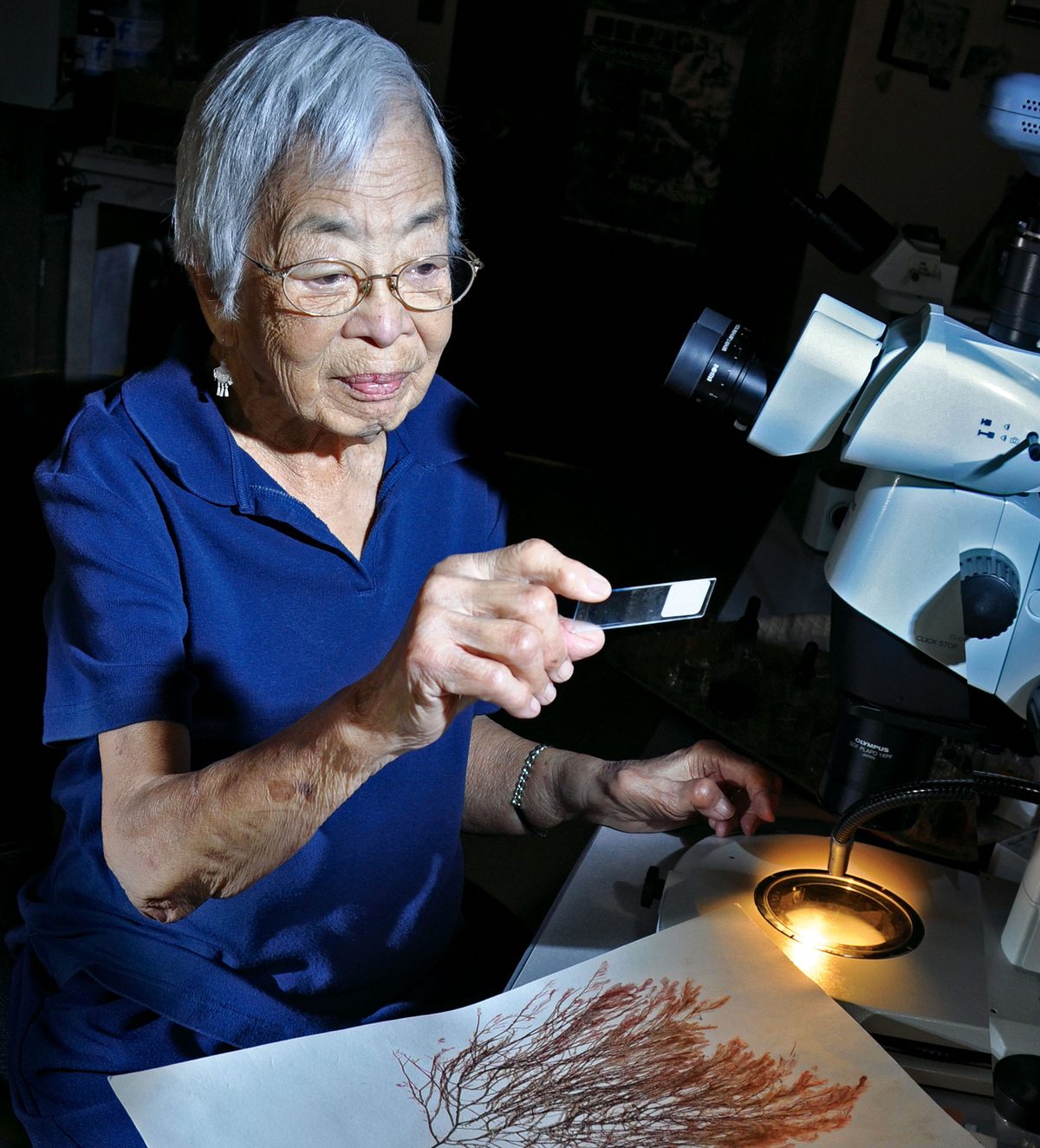

How the ‘First Lady of Seaweed’ Changed Science

Isabella Abbott, the first native Hawaiian woman to earn a doctorate in science, rewrote the book on her beloved limu.

Isabella Kauakea Aiona Abbott’s education in seaweed began early. Through her childhood, she and her siblings combed the shores of Honolulu and Lahaina for edible varieties; Abbott’s Native Hawaiian mother could recognize and name nearly every one of the five dozen or so varieties of limu at their fingertips. At home, they pounded and added salt to seaweeds like the fuzzy, coppery limu kohu (Asparagopsis taxiformis) and the soft, tangled limu wawae’iole (Codium edule). They dipped the branchy, centipede-like limu huluhuluwaena (Grateloupia filicina) in tempura batter and deep-fried it.

As she grew into adulthood, so too did Abbott’s interest in seaweed. By her passing at age 90 in 2010, she had single-handedly discovered more than 200 species and helped to turn the scientific community’s attention to the essential role the plants play in healthy marine ecosystems. Abbott’s work was so prolific that other researchers called her the First Lady of Limu.

There is no doubt, says Stephen Palumbi, colleague, friend, and professor of marine sciences at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, that Abbott’s work was foundational for current research into seaweed, a broad category of algae. Today, scientists are exploring seaweed’s role in marine food webs and human nutrition, as well as its potential for sequestering carbon, mitigating ocean acidification, and even curbing the methane in cow burps.

Isabella Abbott, Izzie to her friends, was born in Hana, Maui, in 1919. She graduated from the University of Hawai’i with a degree in botany in 1941 and earned a Ph.D. at the University of California-Berkeley in 1950, becoming the first Native Hawaiian woman to hold a doctorate in science. That same year, Izzie’s biologist husband Don Abbott joined the faculty at the Hopkins Research Center in Pacific Grove, California, as a professor. Like many scholar-wives at the time, although she held a doctorate in marine botany, Isabella Abbott was eventually hired not on a tenure track but as an underpaid, under-resourced lecturer.

Despite the slight, over the following decade Izzie “became one of the premier experts in the world on algae,” says Palumbi. And finally, Stanford righted its original wrong. When the university started to reevaluate the absence of women in its professional roles in 1972, they began at Izzie’s office door. In a single day, she was promoted to full professor of biology, making her the first woman and the first person of color to hold the title there. The speed of the promotion “was unheard of and it hasn’t happened since,” says Palumbi.

For Abbott, seaweed was more than just a professional interest. She regularly showed up to work events with creations such as zucchini bread, made with bull kelp instead of squash, and led an annual seaweed pickling get-together. Her culinary prowess with kelp was even featured in Gourmet in 1987.

As a researcher, Abbott was prolific. She authored more than 150 journal articles and eight books, including the definitive 1976 study on Pacific Coast seaweed, Marine Algae of California. In it, she illustrates the rainbow of limu beneath the sea: ethereal giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) with its flowing mermaid locks; the mulberry-hued, coral-shaped grapestone or Turkish washcloth (Mastocarpus papillatus); leggy alaria (Alaria fistulosa) whose chartreuse blades can grow up to 99 feet in length.

Abbott was among the first scientists to recognize how marine environments rely on healthy seaweed forests: When kelp habitats begin dying off due to warming temperatures, ocean acidification and other human-induced factors, the entire ecosystem is in trouble. Abbott also laid much of the groundwork for understanding the other half of the story: While failing kelp forests are a sign of a larger problem, flourishing ones are powerful defenses against those self-same threats. The undersea plants don’t just sequester and store carbon, they restore natural upwelling and fill the ocean’s nutrient value chain, says Brian von Herzen, founder and executive director of the Climate Foundation. Rebuilding seaweed habitats can help to rebalance the ecosystem.

Increasingly, groups such as Washington State’s Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF), in addition to analyzing the losses, are looking to the future. PSRF is currently collaborating with the Suquamish Nation to restore a bull kelp forest in an area where seaweed habitats have shrunk by more than 80 percent.

“We’ve been successful thus far in being able to grow seeded kelp lines with nylon thread or twine,” says PSRF deputy director Jodie Toft. When ready, the tiny baby bull kelp are positioned by dive teams, though the group hopes that one day the forests regenerate on their own, without human intervention.

This type of research has roots in the work of early pioneers like Abbott, says von Herzen: “Today we stand on the shoulders of these giants in the seaweed worlds.”

Kelp also increasingly shows promise for fighting ecological degradation out of the water. In 2018, researchers at the University of California-Davis reported that incorporating red algae from the genus Asparagopsis into the feed of dairy and beef cattle reduces the methane emissions they exhale by more than 80 percent. Abbott knew red algae well: In 1967, she identified an entirely new genus of the family which today bears the name Abbotella in her honor.

In their later years, the Abbotts returned to Hawai’i and Izzie joined the faculty at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, where she taught until her passing. While there, she was awarded the Gilbert Morgan Smith medal, marine botany’s most prestigious award, and named a Living Treasure of Hawaii. The title was fitting for a woman who proudly displayed a Hawaiian flag quilt on her dining room wall. The heirloom was made by her grandmother, defiantly, at a time when the flag’s display was banned following the overthrow of the Native Hawaiian government in 1893.

“That was very close to her heart, that quilt,” says Palumbi. “And the history of it tells you a little bit about that time, and growing up that way in the Hawaiian culture.” The First Lady of Limu wasn’t just a marine botanist. She embraced seaweed in all the traditional forms that had sustained the island and its people for generations. After all, wrote Abbott, the human relationship with seaweed began not with scientists, but “with a housewife in search of a pudding.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook