It’s Soul-Crushing, But Don’t Take the DMV for Granted

When rich, reckless drivers started tearing up streets, authorities needed a way to keep people safe.

In May 1913, New Jersey drivers had to take a road test for the first time. For the previous six years, under the state’s first Commissioner of Motor Vehicles, the licensing exam had been designed to be “as easy as possible for automobilists.” Drivers simply had to attest they had read the state’s automobile law and could competently operate a car. Now, they would need to get in their car and “perform the ordinary acts” of driving in order to get a license.

It did not go well. One test-taker hit another car. Another mowed into a barber’s pole, and one backed into a fence. During the first week, 30 percent of the people who took the test failed.

Today, more than six million people are licensed to drive by New Jersey, and passing a driving test is a hallowed rite of passage in America. But navigating the ritual space where this test is offered—the Department of Motor Vehicles—is considered an ordeal to be survived. Drab, confusing, glacial, detested, DMV offices are places we try not to think about unless we’re forced to.

But, hated though they are, writes Ellen Hostetter, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Central Arkansas, DMV offices are critical. They represent a decades-long struggle to answer one of the major questions of American life, starting in the early 20th century: How can people live safely with cars?

“The vast automobile infrastructure we take for granted, that comprises so much of our built environment, had to be invented,” she says.

When cars started appearing on American roads, the hazards they posed were not something people merely accepted. The earliest drivers tended to be wealthy enough to afford these new machines. As Hostetter notes in a new paper in the Journal of Urban History, as early as 1902, newspaper columnists were warning of “automobile scorchers”—”reckless and short-sighted motor vehicle owners who drive their machines at racing speed along suburban and country highways.” Activists and politicians fought for a system to monitor and control these menaces, and soon state laws started to regulate car owners and their behavior. In 1903, Missouri and Massachusetts became the first states to pass laws requiring drivers to have licenses. New Jersey, in 1906, was another early adopter.

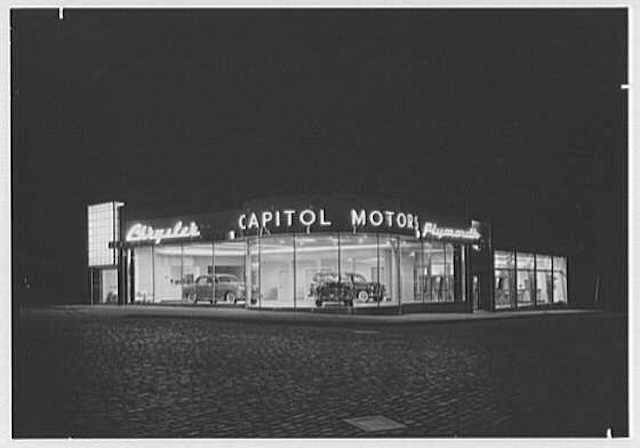

In the early days of the New Jersey DMV, offices were located wherever the agents were—in a machine shop, automobile showroom, or office building. In 1913, when Commissioner Job H. Lippincott took over the department, he negotiated with city halls across the state to take up quarters in those buildings a few days each month to administer written exams. Road tests were conducted on the public streets nearby, with all the hazards that entailed. “One lingering physical mark of the DMV licensing exam landscape was damage done by road tests gone awry—the bent barber’s pole, the scraped arm, and broken bicycle,” writes Hostetter.

This arrangement worked, for a time. In 1914, the state’s DMV issued 70,313 driver licenses—2 to 3 percent of the state’s population was allowed to drive a car. By the 1940s, though, about a third of New Jerseyans, more than 1.3 million people, applied for licenses, which expired en masse at the end of the year. Drivers had to flock to DMV offices for renewals in such crowds that applicants were turned away, even as the state kept increasing the length of the renewal period. The cities and towns that hosted DMVs grew impatient with the traffic and road tests, and as early as the 1920s the department was having trouble keeping its testing sites.

The solution to this jam? The stand-alone, dedicated DMV office and test course, the bane of would-be drivers and renewal seekers across America.

But in the 1950s, when New Jersey opened its first “motor center” at Baker’s Basin, not far from Trenton, the building was heralded as a “Boon to Drivers”—modern, streamlined, and designed to serve drivers. “When it opened in 1957, Baker’s Basin—its size, location, and scope—was certainly a direct reflection of frustration with a system of regulation developed in the early 1900s,” Hostetter says. It was an adaptation to a new reality, where driving was not the domain of a few wealthy “scorchers” but a necessity for growing suburban neighborhoods.

Today, perhaps no space seems more unremarkable than a DMV. I took my driving test at Baker’s Basin and would never have guessed it had once been a pioneering, celebrated space. We accept DMV offices in the same way we accept traffic deaths—as the inevitable cost of convenience and mobility. These mundane spaces, in some ways, help mask the danger of the deal we’ve made as a society.

But part of this culture is changing quickly. States have tried to streamline and automate the functions of the DMV to make it a less dreaded experience. And if the makers of autonomous vehicles are as successful as they dream, drivers’ licenses could become rare or obsolete, along with the public establishments needed to administer them. If DMVs were invented to help curtail the new dangers posed by automobiles, their demise might signal another shift in the transportation landscape of the country—something that will seem remarkable at first, and then eventually fade into the background.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook