Sharks Have a Sixth Sense and It is Terrifying

A Great White Shark at the surface in New Zealand. (Photo: Lwp Kommunikáció/flickr)

A Great White Shark at the surface in New Zealand. (Photo: Lwp Kommunikáció/flickr)

Each summer, sharks get a bad rap, with the mere sight of a dorsal fin clearing entire beaches. Indeed, as the unprecedented seven shark attacks in the span of a few weeks off the coast of North Carolina have shown, sharks are ace killers, apex predators perfected for the hunt. They pick up on the scent of blood from miles away, their sleek, torpedo-like bodies and powerful jaws no match for the unsuspecting fish or seal.

And if that’s not frightening enough, it turns out that these killing machines also have a secret weapon—a sixth sense—that allows them to prey in murky waters or even complete darkness.

Sharks can sense electricity. All animals produce weak electric fields because ion concentrations inside their bodies differ from ion concentrations in the surrounding seawater. This difference produces a slight voltage, which sharks detect at close range—from about half a meter away—when going in for the kill.

“You’re like a battery,” says Stephen Kajiura, a Professor of Biological Sciences at Florida Atlantic University. “The best I can say is it’s like there’s an electric aura around any organism,” says Kajiura, “We don’t have an analogous sense.”

Sharks, always the superlative, are about 10,000 times more sensitive than any other animal with an electric sense, and much more sensitive than even our best measuring equipment. They can detect electric field gradients as small as a billionth of a volt across a distance of a centimeter, making them the best electrical sensors on the planet.

Close up of a tiger shark’s snout, showing the ampullae of Lorenzini pores. (Photo: Lwp Kommunikáció/flickr)

Close up of a tiger shark’s snout, showing the ampullae of Lorenzini pores. (Photo: Lwp Kommunikáció/flickr)

Such stealthy skills are why movies like Jaws, celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, are so terrifying–because they appear to show sharks that can track and outwit humans. But the more that scientists learn about the shark’s remarkable electrical sensitivity, the more it appears we may be able to harness this alien sense not only to protect ourselves from sharks, but also to protect sharks from ourselves.

In 1678, the Italian anatomist Stefano Lorenzini described a mysterious set of pores concentrated on a shark’s head. But it wasn’t until the late 1960s when a Dutch scientist, Adrianus Kalmijn, discovered that these pores sensed electricity. He connected two separate aquarium tanks with metal wires. In one tank was a fish, and in the other, a shark.

Kalmijn noticed that the shark began biting at the wires, which means the shark was responding to the fish’s electric field transmitted by the wires. This observation led him to conduct a series of experiments in 1971 in which he definitively demonstrated that sharks use the electrical sense, rather than odor or vision, to close in for the kill. Kalmijn’s experiments astonished the scientific community—the discovery of an entirely new sense isn’t common. “That’s like discovering vision for the first time,” Kajiura says.

Over the next few decades, scientists realized that the electric sense is common throughout the animal kingdom, at least in aquatic animals (air is a poor conductor of electricity, so the sense is less useful for terrestrial animals). Not only sharks but also stingrays and many other kinds of fish were shown to be electrosensitive. Just a few years ago, scientists learned that river dolphins could sense electricity, the first instance in placental mammals. Even the platypus, that evolutionary grab bag, has electroreceptors studding its bill.

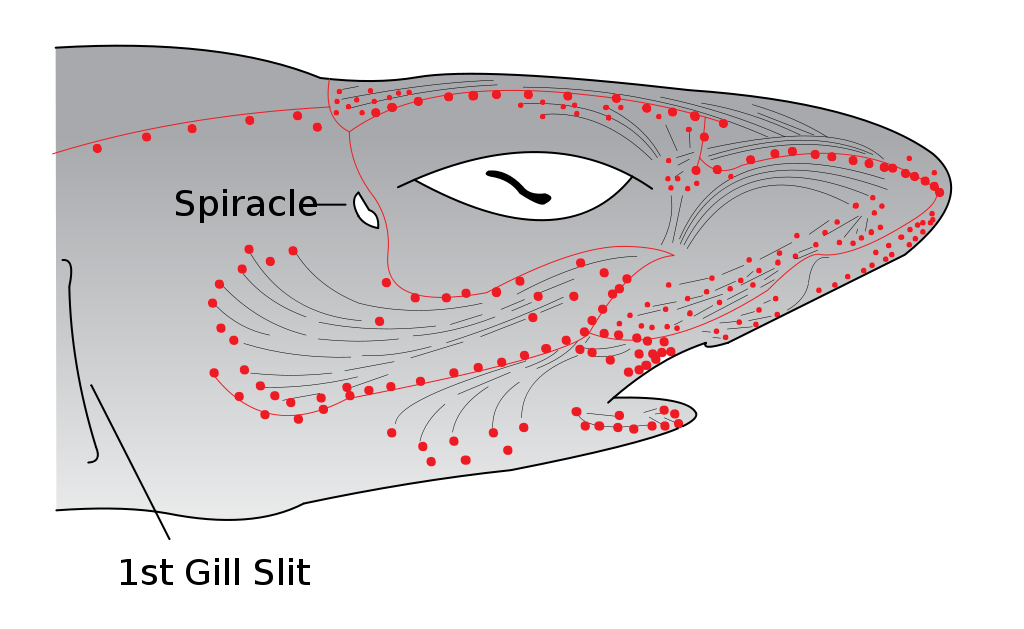

Electroreceptors in a sharks head. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Some scientists believe that in the past electrosensitivity may have been even more widespread. “Most basal groups [of animals] have at least one electrosensitive member,” says Christine Bedore, a professor of biology at Georgia Southern University. “Evolutionarily, electrosensitivity is the primitive condition. Animals may have started out this way and then lost it.”

Humans produce electric fields too, but unlike fish, we are almost completely covered by very insulating skin. This means that our electric fields are mostly contained in our bodies. That said, if we open our mouths underwater, we would suddenly produce a detectable electric field because ions can leak across the mucous membranes lining our mouth and tongue.

“If a shark bites you,” Kajiura advises, “Don’t scream.” Of course, if a shark is already biting you, it’s a bit too late.

Now that we know about the shark’s electric sense, could we design an electrical repellant to protect divers? This idea has been toyed with since the sense was discovered several decades ago, but now there is a diving suit on the market, called SharkShield, supposedly with electrical properties that repel sharks. But shark attacks are so rare that such as suit wouldn’t be necessary unless you were diving in shark-infested waters. Then, Kajiura notes, “You’d have to wonder why you’re doing that in the first place.”

A great white feeds on a whale carcass in South Africa, with the ampullae visible. (Photo: Fallows, Gallagher, Hammerschlag/Wiki Commons/CC BY 2.5)

A great white feeds on a whale carcass in South Africa, with the ampullae visible. (Photo: Fallows, Gallagher, Hammerschlag/Wiki Commons/CC BY 2.5)

But electric repellants could work in the other direction, too—to protect sharks. Sharks are common by-catches of fishing equipment, so scientists are working on systems of magnets and metals that will repel sharks from nets and lines. This will deter sharks from eating the fisherman’s catch, and prevent sharks from getting caught in the equipment.

“This obscure sensory system might actually be used to simultaneously help fisherman and conserve shark populations,” says Kajiura. “That’s one reason why I study this esoteric topic.”

As one of the ocean’s top predators, sharks play a key role in marine ecosystems, yet their numbers in the wild are dwindling. Perhaps with a better understanding of their secret electric life, we can help save them rather than simply fear them.

Hammerhead sharks, whose electroreceptor pores are spread over a larger area. (Photo: Ryan Espanto/flickr)

Hammerhead sharks, whose electroreceptor pores are spread over a larger area. (Photo: Ryan Espanto/flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook