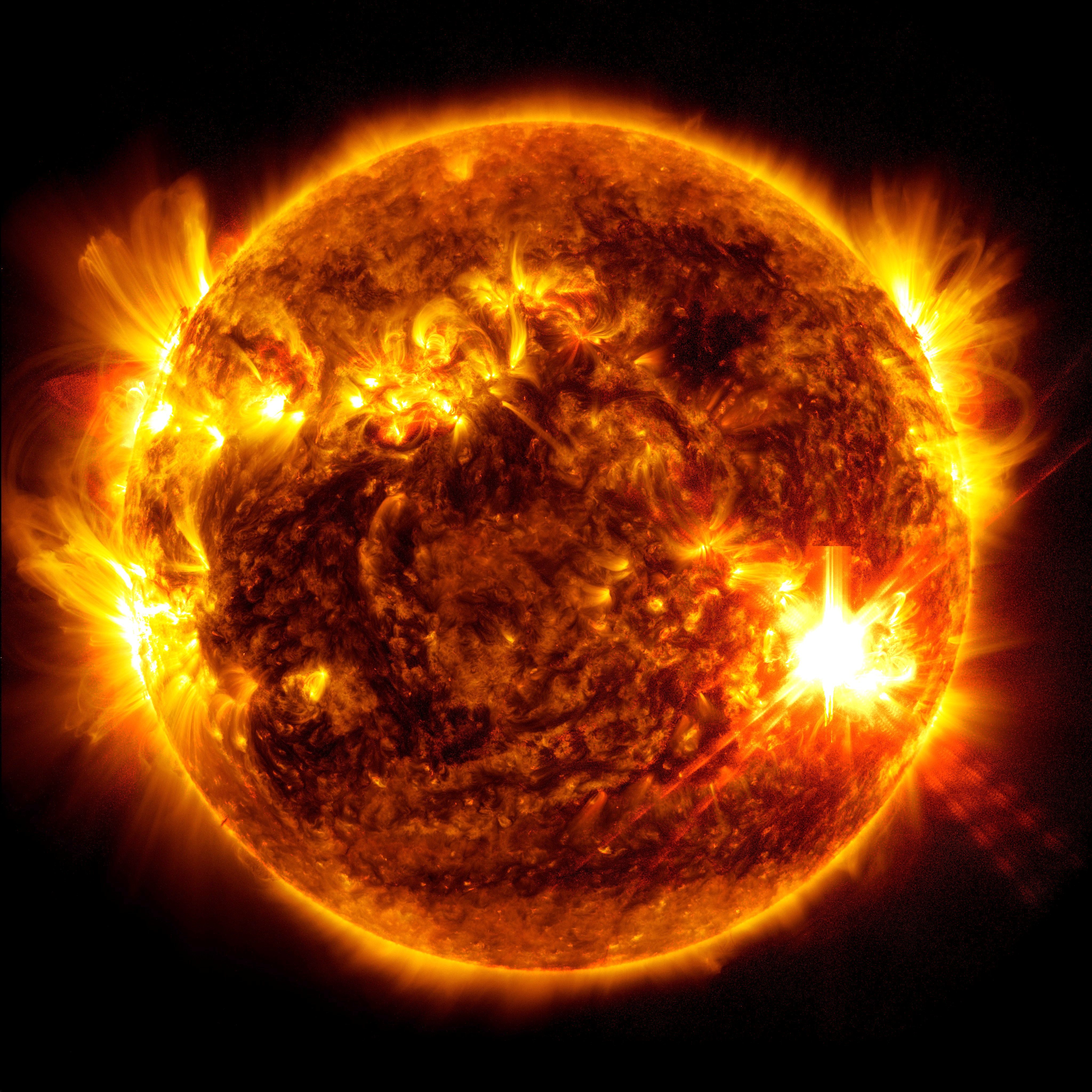

Solar Storms Create Wondrous Auroras—But Dangerous Power Surges

The next potential space voltage could be on the horizon very soon.

While many in the United States marveled at the powerful aurora borealis in mid-May, scientists were watching the event anxiously and trying to work fast. They needed to notify a lot of people to hunker down and prepare for potential damage, even danger, that was coming.

They had to ensure power grids wouldn’t surge. They needed to protect satellites. They even needed to tell astronauts on the International Space Station to climb back down into ships. “You don’t want to be doing a space walk outside of the ISS when there’s a radiation event going on,” says Mike Bettwy, Operations Chief for the Space Weather Prediction Center at NOAA.

Even though a sunspot 17 times the size of Earth was raging millions of miles away, these powerful electromagnetic storms have the ability to disrupt many things on our planet. “We coordinate with the North American Electric Reliability Corporation to take the appropriate precautions needed to prevent widespread issues with the power grid,” says Bettwy. A surge of space voltage in the wrong part of our grid could short it out, but with a bit of warning, technicians can send that voltage into an underutilized area that can handle it.

Some operators must put their satellites into safe mode to prevent damage from solar winds, otherwise we would lose a lot of communication on the ground. And aviation communication can be easily disrupted.

The combined teams at NOAA and NASA do their best to give critical systems some warning time to prepare for solar storms, by studying chronographs of the Sun and comparing those with data from satellites and earthside instruments. “As soon as the solar activity increases, the alerts to grids/comms/satellites are sent,” wrote Teresa Nieves-Chinchilla, Acting Director of NASA’s Moon to Mars Space Weather Analysis Office, in an email. Depending on the level of activity, warning times can vary between a few days and a few minutes.

Solar events in and of themselves are not unique; and frequent, smaller solar storms are not something the average citizen needs to worry about. But the storm in early May was one for the history books.

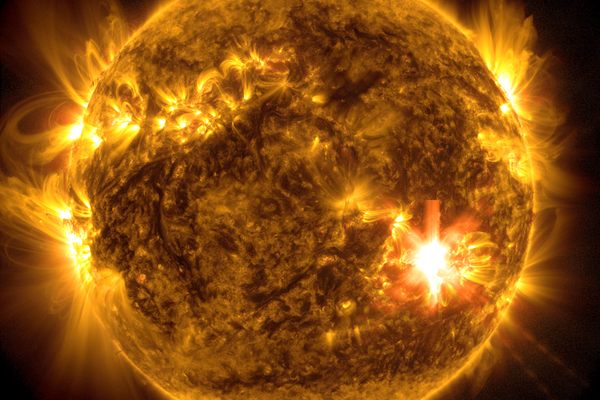

Watching the skies through a series of powerful telescopes, magnetometers, and satellites, the team at NOAA realized the powerful solar storm would rival those seen in 1958 and 2003. It ended up exceeding expectations. Scientists believe it was one of the most intense displays of the aurora borealis in 500 years. The flares released by this storm were X-class, which is the strongest type of flare. Waves of energy from these solar machinations traveled at the speed of light towards Earth—registering a G5 on the geomagnetic storm scale, the strongest rating.

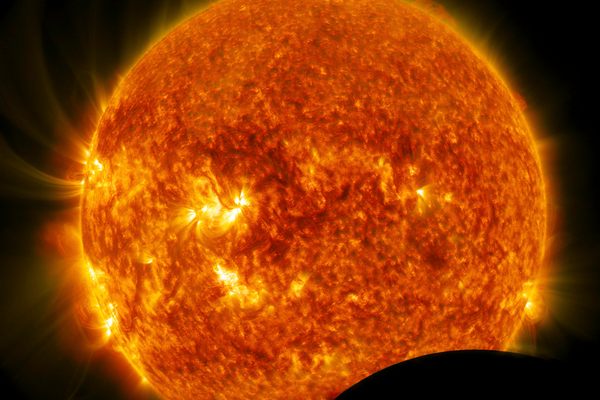

This storm was so strong that it was falsely registered as an earthquake by one team out of the University of Victoria, with forces penetrating deep into the ocean and disrupting the Earth’s magnetic field over 1.5 miles below the surface of the waves. The aurora borealis, typically contained to the most northern regions of the hemisphere, was suddenly visible across much of the United States.

Eventually, the Sun rotated and the damaging solar winds were no longer directed our way—but now scientists are waiting to see how intense that same storm will be once the Sun rotates again. It takes about 27 days for the Sun to rotate once, so Bettwy and Nieves-Chinchilla’s teams remain on alert. Typically, solar storms do lose intensity as coronal mass ejections (eruptions, in Earth terms) burn up the gasses fueling their activity.

The problem is that while technology has greatly improved, humans still can’t see the back side of the Sun. “When [the storm] comes back on the visible side of the Sun, it will be interesting to see how it’s changed,” says Bettwy. Will critical infrastructure systems need to work quickly to protect themselves again?

We are far from a time where we can predict solar weather with the accuracy of terrestrial weather, says Bettwy, but it’s improving every day. “That’s why it’s really, really critical to have constant monitoring and imaging,” he says. “Now, if we see in a satellite image of a solar flare, we can actually run a model to try to predict how it is going to interact with the Earth’s atmosphere.” That wasn’t possible in the past, which meant solar storms were potentially much more dangerous before.

Nieves-Chinchilla says she’s proud of how they handled this massive event; she’s not nervous for whatever is happening on the back side of the Sun at the moment. “We have been working together for the past 10 years to prepare our society for adverse space weather events,” she says. The minimal impact of this record breaking storm is a testament to those efforts, but scientists can’t relax yet. “There are still things to improve. There is work now to evaluate the actions taken and the impacts.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook