San Francisco’s Famous Sourdough Was Once Really Gross

Gold miners made themselves sick on smelly, hard loaves.

Long before it became a viral food trend or social-media sensation, American sourdough was surprisingly gross.

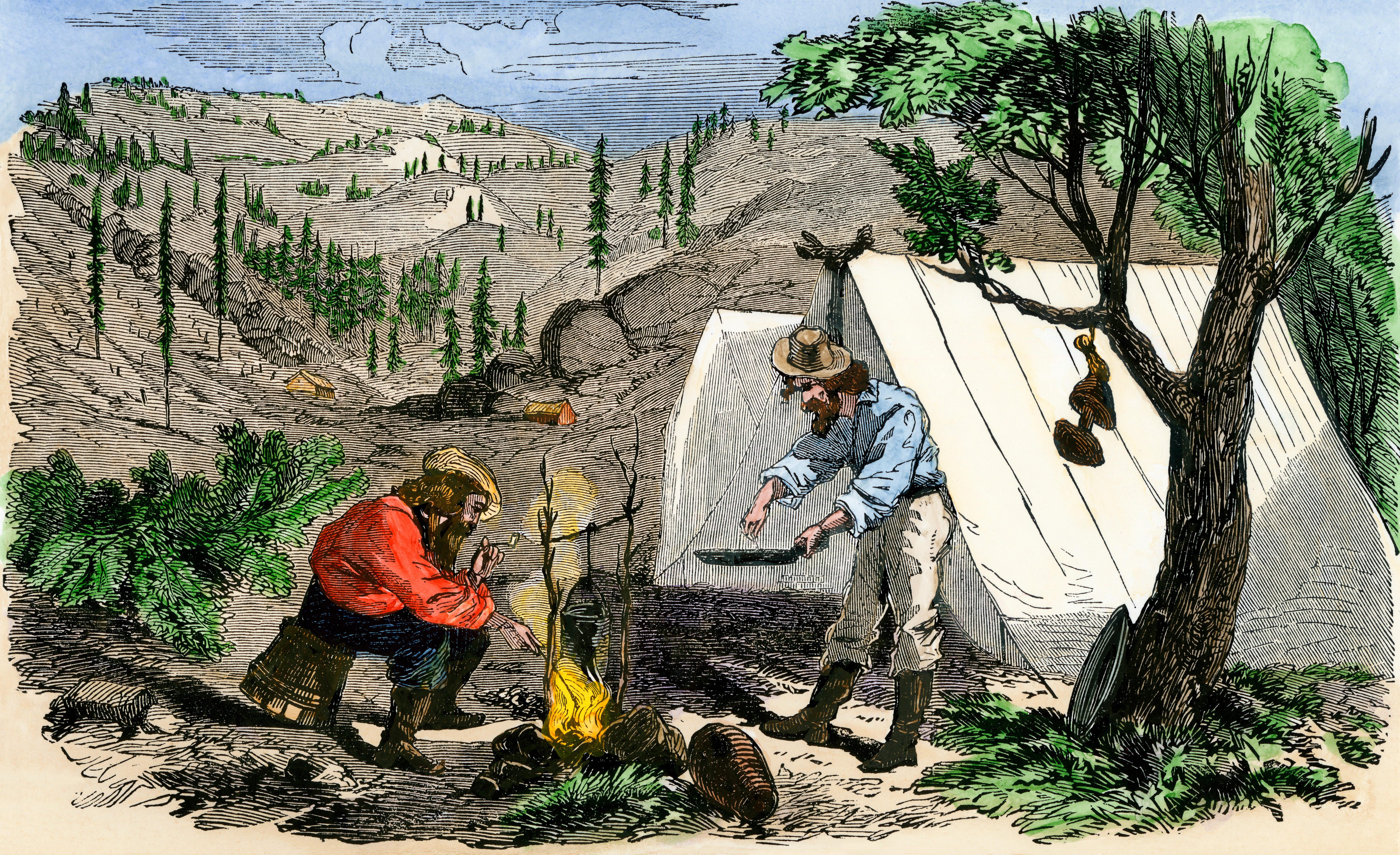

San Franciscans proudly trace their city’s iconic bread back to the Gold Rush of 1849. The men who flocked to Northern California in search of gold made bread in their wilderness camps not with store-bought yeast, but with their own supply of sour, fermented dough.

Their tangy, funky bread became so closely associated with frontier life that veteran miners were called “sourdoughs.” And supposedly, when the 49ers shared their culinary creation with newly-emigrated European bakers in the city, the famous San Francisco sourdough loaf was born.

But to food historians, this story smells a bit sour. Letters, diaries, and newspaper articles written by and about the 49ers, lumberjacks, and pioneers of the American West are full of complaints about horrible and inedible sourdough. Could bad bread really have inspired San Francisco’s most beloved loaf?

In 1849, when gold miners began arriving in San Francisco, most Americans didn’t bake or eat sourdough bread. American bakers typically leavened their bread with “barm” (a yeast derived from beer brewing) or one of several relatively new commercial yeast products. These commercial yeasts were easy to work with, didn’t require constant maintenance, and produced reliable results. They also produced bread that appealed to American taste buds.

Most 19th-century Americans preferred bread that was sweet rather than sour. According to one 1882 advice book for housekeepers, the “ideal loaf” was “light, spongy, with a crispness and sweet pleasant taste.” Sour bread was a sign of failure. As a result, bread recipes from the period used commercial yeasts along with considerable amounts of sugar or other sweeteners to speed up fermentation and avoid an overly sour flavor.

The 49ers didn’t bake sourdough bread because they liked it, but because they lacked better alternatives. While some miners brought commercial yeasts, baking powders, and self-raising flour with them to California, their supplies eventually ran out. Food was expensive in frontier boomtowns, and store-bought yeasts and self-raising flour were luxuries. Sourdough required only flour, water, and fresh air. A sourdough “start” needed care, attention, and regular feedings but offered an inexhaustible, self-perpetuating supply of leavening agent, even in the wilderness.

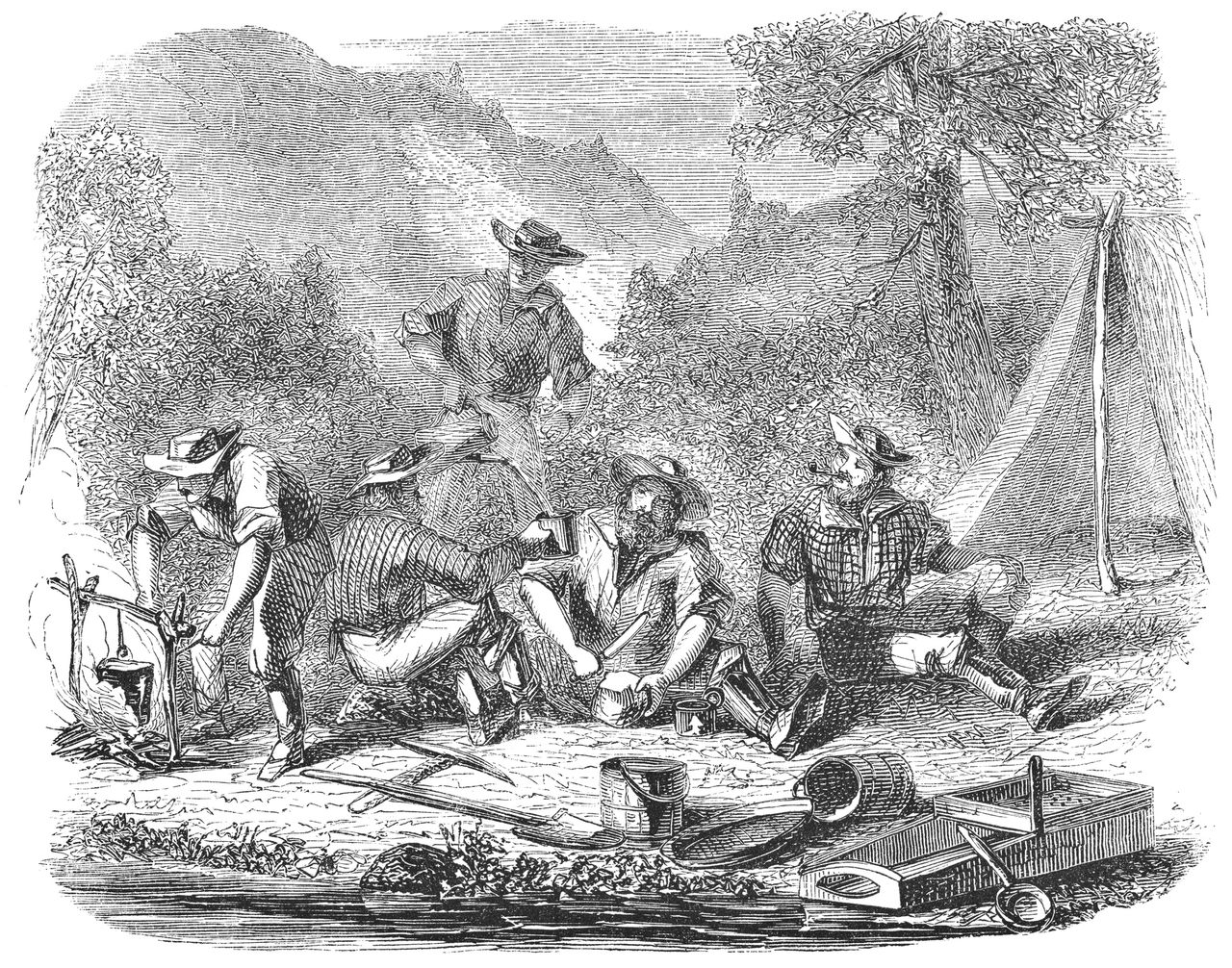

But, as many modern bakers know, making good sourdough bread is tricky, and most miners were not experienced bakers—a combination that often produced disastrous results. Miners’ accounts from the period feature many complaints about bread. In the early days of the gold rush, their camp baking efforts were frequently described as overly sour and poorly risen. According to one description written by a former 49er, “as a general thing miners’ bread was but sorry, sad stuff.”

Bread was baked under difficult circumstances—outdoors, over a campfire or hot coals, and sometimes in the same flat pan used for panning for gold—leading to inconsistent and unsanitary results. Miners frequently experimented with their dough to try to reduce its sourness. Some even tried mixing in copious amounts of baking soda, but this left the bread with yellow streaks and an unpleasant flavor.

One account, written by a veteran miner in Idaho, joked that a newcomer to camp might mistake a loaf of sourdough for a rock, because the bread had been streaked yellow by the addition of too much baking soda and then left out overnight on the ground to collect dirt and green mildew.

Sourdough starter itself could also be revolting. A family visiting Yosemite in the late 1860s asked a local miner if they could borrow some starter, as they’d run out of yeast. The miner was happy to oblige but couldn’t find his starter anywhere in his untidy frontier cabin. According to the story, he eventually “got a great big stick and swung it back and forth under the bed and out came old shoes, socks, dirt, and a saddle. Away in the back near the corner he scraped out a great big ball of sour dough.” The storytellers’ mother was forced to cut away layers of dirt and mold from the outside of the ball in order to find clean, uncontaminated dough that could be used for baking.

Sourdough baked by pioneers wasn’t just gross and unappetizing; it could also make you sick. The diary entry of a Montana lumberjack new to camp included this typical report:

“Made sour dough bread today, just about as heavy as green lumber. I think the recipe I got from Poker Bill is at fault. My partner had the stomach ache. Did not tell him it was the bread.”

Complaints of indigestion were common, although the other camp foods—beans, bacon, and black coffee—may have been equally responsible. Press reports from the period even blamed contaminated sourdough starter for the deaths of bakers.

Across the American West, sourdough was considered a food for unmarried men who didn’t know how to cook. These men were like their bread: rough, tough, and they smelled a little bit funny. But the ultra-masculine frontier lifestyle was supposed to be temporary. These men were expected one day to return to civilization and enjoy the “sweet” and “light” bread baked by their mothers or wives.

So it’s worth asking: If sourdough bread baked by miners was so terrible, how did it become one of San Francisco’s most beloved foods?

It all came down to the success of the city’s French and Italian bakeries. The earliest of these, Boudin, was founded in 1849 by French immigrants. These professional bakers didn’t need to borrow starter or baking techniques from miners, because they were already experts in the use of levain. This sourdough technique was widely practiced by bakers in France and Italy. Other famous bakeries that popularized sourdough in the region around the turn of the century—Parisian, Larraburu, Toscana, and Colombo—were all founded by French and Italian professionals, not former miners.

These bakeries described their bread as “French bread” or “Sour French bread,” linking it to European culinary traditions, not the trial-and-error baking of the American West.

But it was nostalgia for the American West which ultimately rehabilitated sourdough. The first efforts to rescue the bread’s reputation came at the start of the 20th century, when social clubs for aging miners, sometimes known as “Sourdough Clubs,” encouraged members to romanticize their past struggles with biting insects, sleeping outdoors, and even sourdough.

By the second half of the 20th century, tourism boards in San Francisco were placing the 49ers at the center of the city’s history, idealizing life on the frontier and playing up links between the Gold Rush and the City by the Bay. San Francisco bakeries joined in, crafting stories about partnerships between bakers and miners and attempting to market the bread nationwide.

This paid off. Sourdough became so trendy that one 1986 newspaper even called it “he-man bread,” that had “carried cowboy, trapper, prospector and pioneer across the western frontier.” For sourdough’s new fans, the bread offered “a harkening back to the wholesomeness of the old ways of living,” and promoted values like authenticity, hard work, and the value of handcraft. Sourdough, once a rank, rock-hard survival food, had become the bread that fed the West.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook