The World’s Largest Speedo Collection Almost Oozed Away

In 2012, Australia’s Powerhouse Museum discovered that something strange was happening with some of their swimsuits.

The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, Australia, had a problem: Their Speedos were oozing.

Since 1991, the institution has been home to the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of Speedo swimwear. The earliest suits in the archive date back to the 1930s and are made from navy blue cotton knitwear; more recent designs, such as the LZR Racer full-body suit, are so technologically advanced that they’ve been banned from the Olympics for making swimmers too fast. But the oozing, which conservators discovered in 2012 during a routine check of the collection, was limited to Speedos produced in the 1980s and early ’90s.

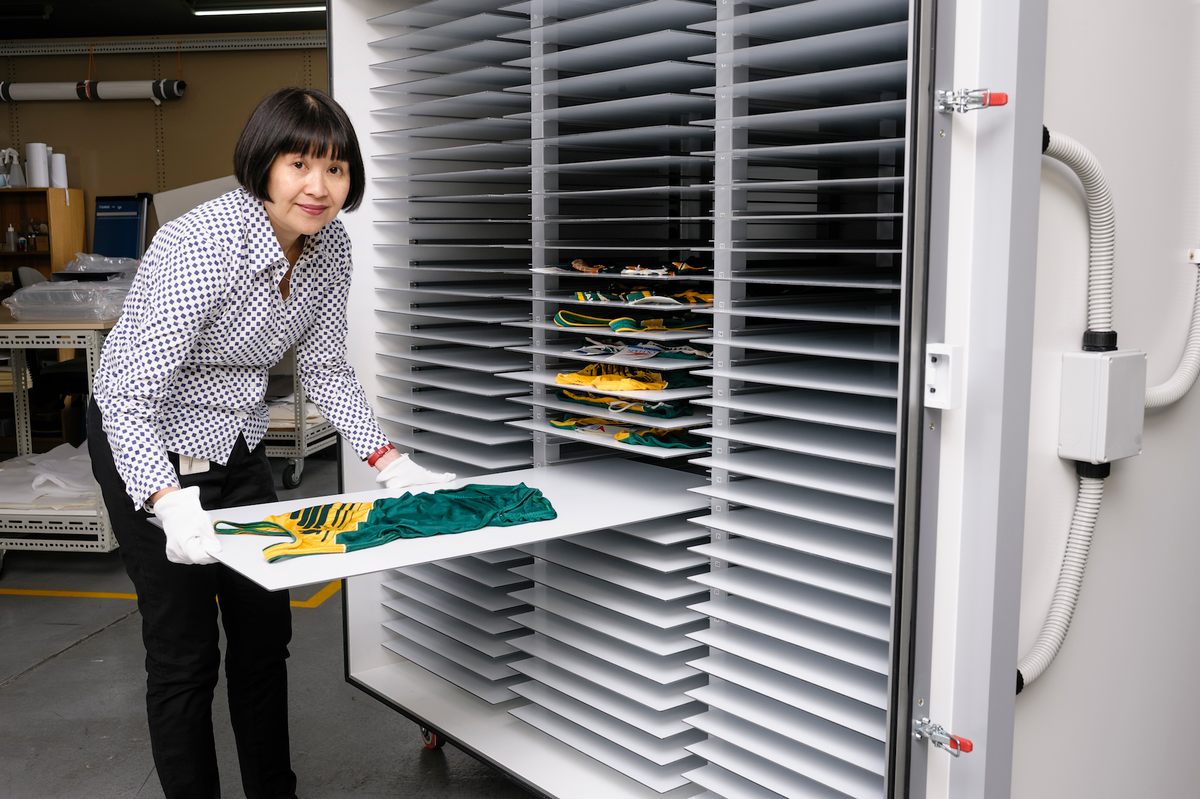

“It was a bit of a shock, in fact, to find this group of swimwear deteriorating in storage where it’s kept in the dark,” said Suzanne Chee, a textile conservator at the museum. “We keep our relative humidity constant and the temperature down in our storage facility, so something strange was happening in the drawers.”

To diagnose the affected swimsuits, Chee and her fellow conservators had to first determine their chemical composition. So, they selected a suit from the 1986 Commonwealth Games and subjected it to a series of in-house tests. (They also sent some fibers to the University of New South Wales for additional analysis.)

Eventually, they fingered the culprit: The Lycra in the suits contained ester-based polyurethane, a plastic that deteriorates when it comes in contact with water. Even in the Powerhouse Museum’s climate-controlled storage area, there was enough moisture in the air to cause a gradual breakdown in the chemical bonds that resulted in stickiness and oozing.

These Speedos fell victim to what conservators call “inherent vice”—when the materials that make up an object cause it to deteriorate, even self-destruct. Despite its flashy name, inherent vice is “no joke,” notes Sarah Scaturro, head conservator for the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “It’s a really distressing characteristic of an object for a conservator.” Certain methods of storing or displaying can help stabilize the item temporarily, she says. “But in the long term, we know that there’s nothing that can really be done to stop it” from falling apart.

The issue isn’t limited to swimsuits, or even clothing. The hand-drawn animation cels from classic Disney films such as Snow White, for instance, were manufactured with unstable plastics that have since caused extensive wrinkling and yellowing. But inherent vice has resulted in a strange quirk of textile conservation: A cellulose acetate dress from the 1960s, for example, could be in far worse condition today than Coptic linen dating back to the 4th century. It all depends on the composition of the textile—natural fibers like linen, cotton, and wool are relatively stable. But add in metallic dyes or a plastic like polyurethane, and there will be a problem somewhere down the line.

Yet for swimwear, in particular, the risk is worth it. Newly-developed materials like spandex and nylon (or the more recent “Fastskin,” modeled after the skin of a shark) can determine an Olympic champion.

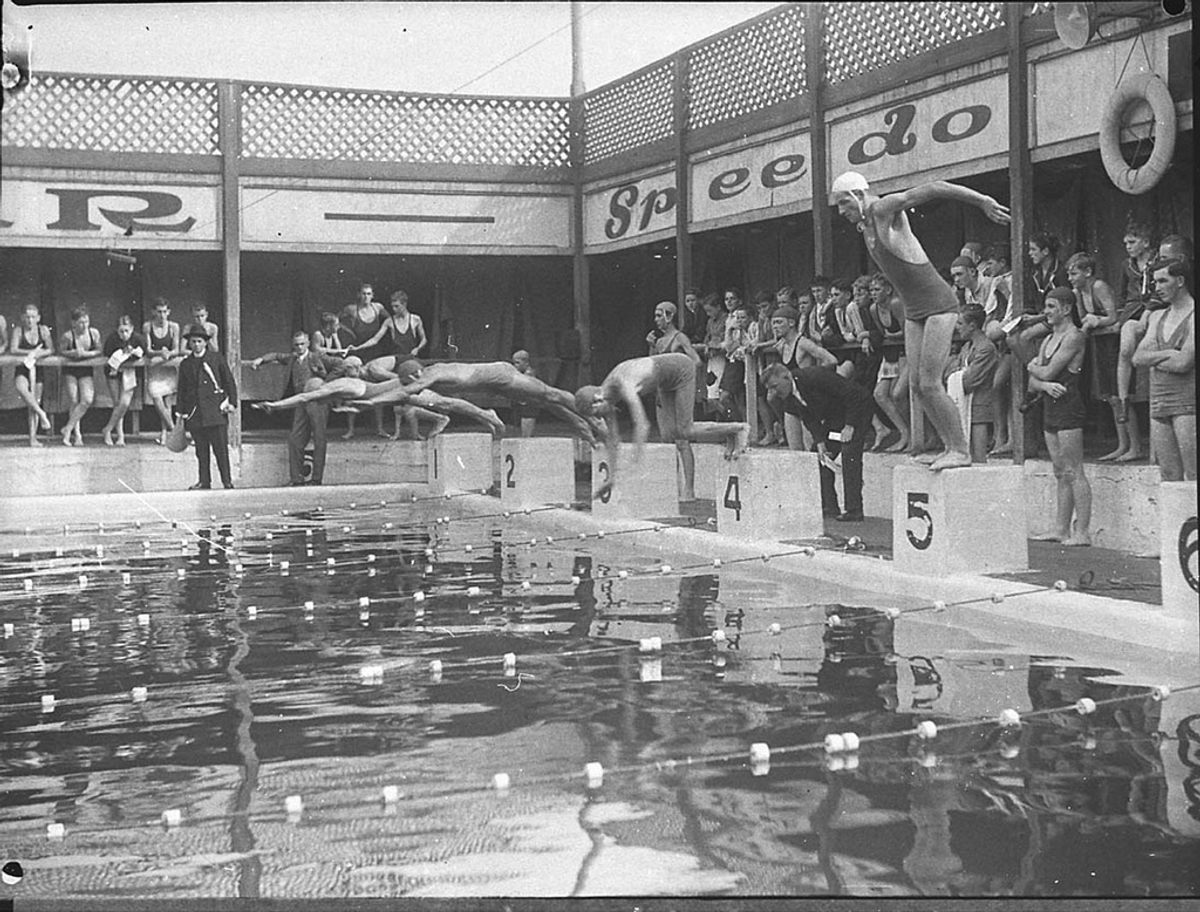

Speedo didn’t start out making swimsuits. In 1910, a young Scot named Alexander MacRae moved to Australia; four years later, he founded MacRae and Company Hosiery to manufacture underwear and knitwear. But as beach culture began to flourish in Sydney in the 1920s, the company diverted much of its energies into making early bathing suits. (The name “Speedo” emerged from a 1928 staff competition to brand these new garments, in which the winning slogan was “Speed on in your Speedo.”)

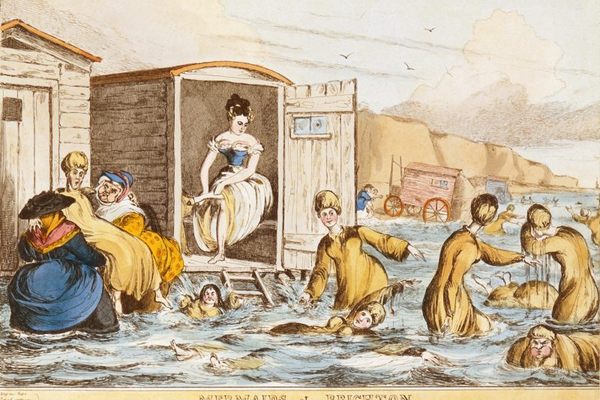

Made of cotton and wool, these suits weren’t necessarily uncomfortable, “just heavy,” says Powerhouse’s curator of fashion and dress Glynis Jones. “Once you get a lot of water into wool and cotton, you get a lot of drag from them.” A better option was silk, which is lighter—but also more expensive and much more revealing when wet. “Concerns around modesty were really significant in the ’20s and ’30s,” Jones noted, “so to have this really clinging swimsuit was not seen as desirable.”

Speedo experimented with silhouette as well as material, revolutionizing competitive swimwear in the late 1920s with the introduction of the racerback, which kept straps from slipping off mid-swim. “That was them starting to think about streamlining, thinking about speed through the water with those innovations in the design,” Jones notes.

Then came World War II, which was followed by the widespread introduction of brand-new, synthetic materials. “There was this moment of technological optimism, where technology was seen as the solution to everything,” Scaturro says. “In fact, there was a moment where, if you look through the manufacturing and industry literature, they were worried that they were going to run out of natural fibers to make clothes. It was seen as a necessity to have fibers that were manmade, it was seen as actually helping humanity to make these fibers.”

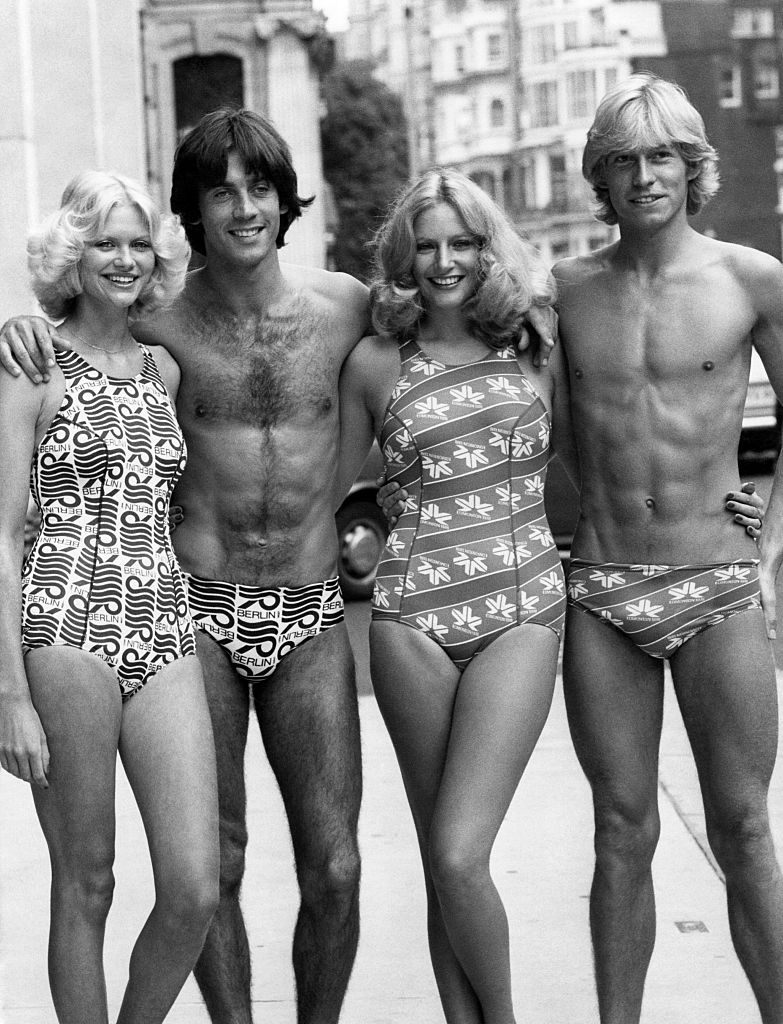

Even without this context, swimwear would have embraced synthetics. Nylon, unlike cotton or wool, is light, dries quickly, and has good stretch—ideal qualities for a bathing suit. Soon, Speedo was hammering out deals with manufacturers like British Nylon Spinners. “They were very keen to promote this new wonder fiber,” notes Jones.

In 1969, American chemical company DuPont opened an Australian branch and began to tinker with with nylon/Lycra mixes specifically for racing swimwear, which had “more stretch and were lighter than fashion fabrics,” Jones adds. They granted the now-dominant swimwear company exclusive rights to use their textiles, making Speedo the first swimwear company to design with a nylon/Lycra blend.

Of course, it’s also the Lycra that caused the oozing in the 1980s suits. There are actually four kinds of plastics that will undoubtedly show inherent vice, says Scaturro, but the one she’s most worried about—polyurethane—is the one that may have doomed a decade of Speedos.

“The beauty of polyurethane, the reason why it’s used so much in the industry, is that it’s infinitely customizable,” she explains. “You can totally do a boutique style polyurethane for anything you need.” This helps to explain why only a decade of Speedos were affected in the Powerhouse collection. Invista USA, who supplied the Lycra for these suits, briefly changed their recipe to include ester-based polyurethane during that period.

But identifying the precise chemical composition of polyurethane requires time-consuming scientific testing. (After six years on the job, Scaturro is still working her way through analyzing the Met Costume Institute’s collection of more than 35,000 items.) “I feel like it is the sleeping time bomb in a lot of fashion collections,” she warns.

At the Powerhouse Museum, they’d identified the bomb—now they needed to figure out how to defuse it. Since the issue was moisture, they hypothesized that a low-humidity chamber might do the trick. So they built a tank and tested a few suits in there. When the outcome was encouraging, the museum secured a grant to build a bigger storage chamber where they could store the approximately 80 affected swimsuits indefinitely.

This issue has actually changed the ways in which the museum collects, says Jones. The institution has an ongoing relationship with Speedo Australia, and these days, she requests two examples of every competition swimsuit rather than just one. That way one can stay in storage and never get displayed, hopefully to increase its lifespan.

As both Chee and Jones are acutely aware, the 1980s swimsuits will not be the last with conservation issues. “In the 21st century, where there’s lots of plastics coming in and different compositions of the plastics, it’s going to be an uphill battle,” Chee notes. New materials continue to be a linchpin of Speedo’s business. Although the full-body LZR suit may be banned, they continue to use “Fastskin” in their most recent designs for Olympic athletes. And as each one of these high-tech suits eventually enters the Powerhouse’s collection, it’s overshadowed by a looming question: How long before things start going wrong? Because in the end, the designers aren’t thinking about longevity—they’re thinking about speed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook