The Resilience of Sri Lanka’s Musical, Mobile Bakeries

Faced with stiff competition and a strained economy, these Beethoven-blasting bread trucks fight to stay afloat.

When Ludwig van Beethoven composed “Für Elise” in 1810, he may have hoped for its success in theaters or in Austrian music halls. He could never have guessed that “Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor” would one day become ubiquitous on an island more than 4,700 miles away.

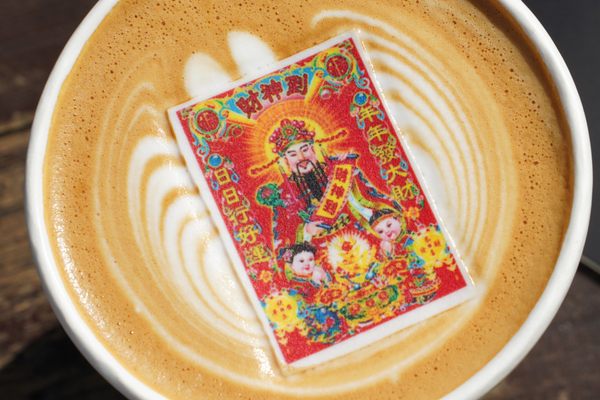

And yet, every morning in Sri Lanka, Beethoven’s classic can be heard floating over paddy fields in the countryside, or competing with the sound of the traffic in the cities. The music blares—noisily, tinnily, and out of tune—from three-wheeled tuk-tuks, each fitted with glass cabinets and a rooftop speaker system. It’s the soundtrack to choon paan: Sri Lanka’s musical, mobile bakeries.

Over the past 20 years, choon paan (loosely translated as “music bread”) have become woven into the fabric of this small island nation. Twice a day, in the early morning and at evening teatime, they trundle through villages and urban residential areas, selling freshly-baked goods, each bun still deliciously rich with smoke from the wood-fired oven. Stacked neatly inside the glass cabinets are fluffy white loaves for mopping up dhal, sticky sugar-coated buns filled with jam, submarine rolls packed with chicken and cheese, and (if you’re lucky) parippu vada, or crispy lentil fritters. Buying from the choon paan tuk-tuk is a social event, the music a cue to run out and join your neighbors in line.

Choon paan have been around for nearly as long as tuk-tuks have been in Sri Lanka. Three-wheelers only became widespread in the late ’90s, and it wasn’t long before bakers started using tuks to sell bread to far-away neighborhoods. These were the early days of mobile phones, and first-generation choon paan drivers held up their devices to makeshift speaker systems, and blasted pre-downloaded ringtones to attract hungry customers. “Für Elise” was the one that stuck, but it could just have easily been “Ode to Joy” or “Greensleeves.”

“I remember first seeing a choon paan, and getting so excited by these bakeries on wheels,” says Pushpa Jayanthi, who with her husband has owned a village bakery for well over four decades, and a choon paan operation for two. “We used to bake buns and supply them to other shops, but every evening they’d return the items that didn’t sell. With choon paan, we can keep driving until everything’s sold.”

Most Sri Lankans recall fond memories of the choon paan, of waking up to fresh bread in the morning or chasing the tuks down their street as children (in many towns, the three-wheelers are known for their “blink-and-you-miss it” approach to trade). “The music has always been there,” says Mohamed Safras, a chef who grew up in a small village in Sri Lanka’s Southern Province. “When we were children, we would lie in bed and the music would play round and round and round in our heads.”

The mobile bakeries are undeniably charming, but the vehicles take on different significance for different communities. For the urban middle classes, the choon paan tuk-tuk is a nostalgic reminder of simpler times. A reverence for teatime is one of Sri Lanka’s most prevalent colonial hangovers, and the tuks provide the perfect after-school treat for small children. But for those in rural communities—especially working-class families without their own means of transport—a visit from the choon paan man is a necessity. In some cases, no choon paan means no lunch.

In their relatively short life, choon paan haven’t had an easy ride. After booming in the 2000s, the next decade brought heavy competition from chain bakeries, pressure from app delivery services, and a government-imposed ban on playing music above a certain decibel level.

But just as the bakery tuks began disappearing off the roads, the global COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a choon paan revival. When the rest of the island was ordered to stay at home, choon paan trucks sprung into action.

“Customers had no other way of buying bread, so we made a lot of money,” says Jayanthi. In the cities, choon paan drivers were quick to mobilize: “Overnight, choon paan returned to the streets,” says Iman Saleem, a journalist and culture expert from Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital. “They were much more agile than, say, UberEats, who had more hoops to jump through to expand to meet demand.” Like Zoom meetings and living-room yoga, buying from the choon paan quickly became part of the lockdown routine.

Fast-forward to today, and—once again—the future feels uncertain. Sri Lanka is slowly recovering from a crippling post-COVID economic crisis, which has sent the cost of basic necessities such as food, fuel, and electricity soaring.

In rural areas, many choon paan owners have been forced out of business by the vastly inflated price of imported flour and restrictions on petrol consumption. Piyadasa Kumara, a self-employed village baker on Sri Lanka’s south coast, stopped his choon paan operation seven months ago. Today, his tuk sits unused in a corner of his bakery, but the air is still thick and sweet with smoke and the smell of baked bread. Just three days a week, Kumara bakes a batch of simple round, white buns, which he supplies to local vendors. Three days’ worth of bread is all he can afford to bake, and all that there’s demand for.

Elsewhere, in the small town of Habaraduwa, Mohamad Cassim works in a bakery that was previously known for its thriving choon paan business. “It is just not worth it anymore,” he says. “So many people can’t afford to eat in-between meals. And the government quota of four liters of fuel per week won’t get us anywhere when we’re stopping and starting throughout the villages.”

While the fuel and flour squeeze can be felt island-wide, it is particularly pronounced in rural areas. Compared to city bakers, village choon paan drivers have more ground to cover between sales, and serve an increasingly poverty-stricken customer base. The number of Sri Lankans living below the poverty line nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022, and 80 percent of this group live in rural communities. For village traders, it’s a catch-22: “We used to do ten-rupee items, but we can’t offer anything for that amount now,” says Jayanthi, who sold two of her three tuk-tuks last year. “Now, the lowest price we can do is sixty rupees, which is more than some families can afford.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the story of choon paan in Sri Lanka is a story of wealth disparity. While rural bakery owners are struggling to stay afloat, the choon paan trade in Colombo is thriving. After pausing operations during the worst of the crisis, today drivers in the capital city have returned to the streets—in even greater numbers than pre-Covid—and are back to their usual tricks. “The biggest problem now is that you can’t really catch them,” says Nazly Ahmed, a Colombo-based photographer. “You hear the music, but by the time you’re out on the street they’re long gone, off to find their regulars.” There’s also a new breed of musical tuk appearing: choon paan vehicles selling soft drinks, snacks, and household essentials to boost their income streams and compete with the chain bakeries.

Choon paan tuks make up just one small part of Sri Lanka’s ever-evolving street-food culture. But there is something uniquely compelling about the vehicles, and something deeply comforting about their familiar jingle. Today, the fate of the choon paan is tied to the country’s economic recovery, but most people are confident that there’s a place for these mobile bakeries in Sri Lanka’s future. With any luck, choon paan tuk-tuks will return to their former glory, and Beethoven’s classic will be heard at teatime for many years to come.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook