During the Space Race, Gas Stations Gave Away Free Maps to the Moon

Standard Oil was not about to be left earthbound.

Humans attempted to map the lunar surface long before Galileo famously trained his “spyglass” on the moon in 1609. At Knowth, a Neolithic site in County Meath, Ireland, for example, a 5,000-year-old rock carving depicts what appears to be Mare Imbrium, Mare Frigoris, and Mare Serenitatis. William Gilbert sketched lunar maps in the early 1600s, around the time he became Queen Elizabeth I’s private physician. And the English mathematician Thomas Harriot recorded the moon’s features with the help of a telescope four months before the better-known Italian astronomer did.

Lunar maps became increasingly sophisticated as telescopes became more powerful and printing techniques more advanced. Johann Baptist Homann, the Imperial Geographer of the Holy Roman Empire, included one with his colorful 1716 world atlas. Tabula Selenographica features two views of the visible hemisphere alongside three insets that illustrate the Moon’s phases—all floating in a bubble-gum pink sky. In 1834, Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich von Mädler, of Germany, produced the most detailed lunar map of its day, using a 9.5-centimeter refractor at Beer’s Berlin observatory. At more than 10 square feet, Mappa Selenographica prefigured the detail of Rand McNally’s large Official Map of the Moon, from 1958, based on photographs provided by the U.S. Air Force.

Popular selenography, or the study of the moon’s surface, went into hyperdrive 50 years ago, as the United States and the world prepared for the Apollo 11 landing on July 20, 1969. And Standard Oil—the behemoth behind countless 20th-century road maps—was not about to be left earthbound. It commissioned two distinctive maps that would go where none of its free road maps had gone before—the Moon.

Companies like Standard Oil got into the mapping game in the early 1910s, as Americans began logging more and more miles in their new automobiles. Gas station giveaways functioned as indispensable Garmins and Tom Toms: Updated annually, they were how motorists navigated the nation’s quickly developing highway network. Maps were particularly attractive “aides to product sales,” explained the General Drafting Company of New Jersey, which designed many of them for Standard Oil’s Esso and Humble Oil brands, because they were such durable vehicles for 20th-century brand promotion. “People just don’t throw away maps,” General Drafting assured its commercial clients. “Not even free maps.”

Despite the lack of roads and gas stations on the moon, Standard Oil recognized the marketing potential of the Apollo program, and it hired General Drafting’s competitor Hammond Incorporated of Maplewood, New Jersey, to produce two offset lithographic maps. Printed sometime after November 9, 1967, when NASA launched Apollo 4, they combine lunar geography, photography, and spacecraft illustrations, along with celestial facts and purple prose: “The pale moon hangs like a distant target against the jet-black background of outer space,” Map of the Moon explains.

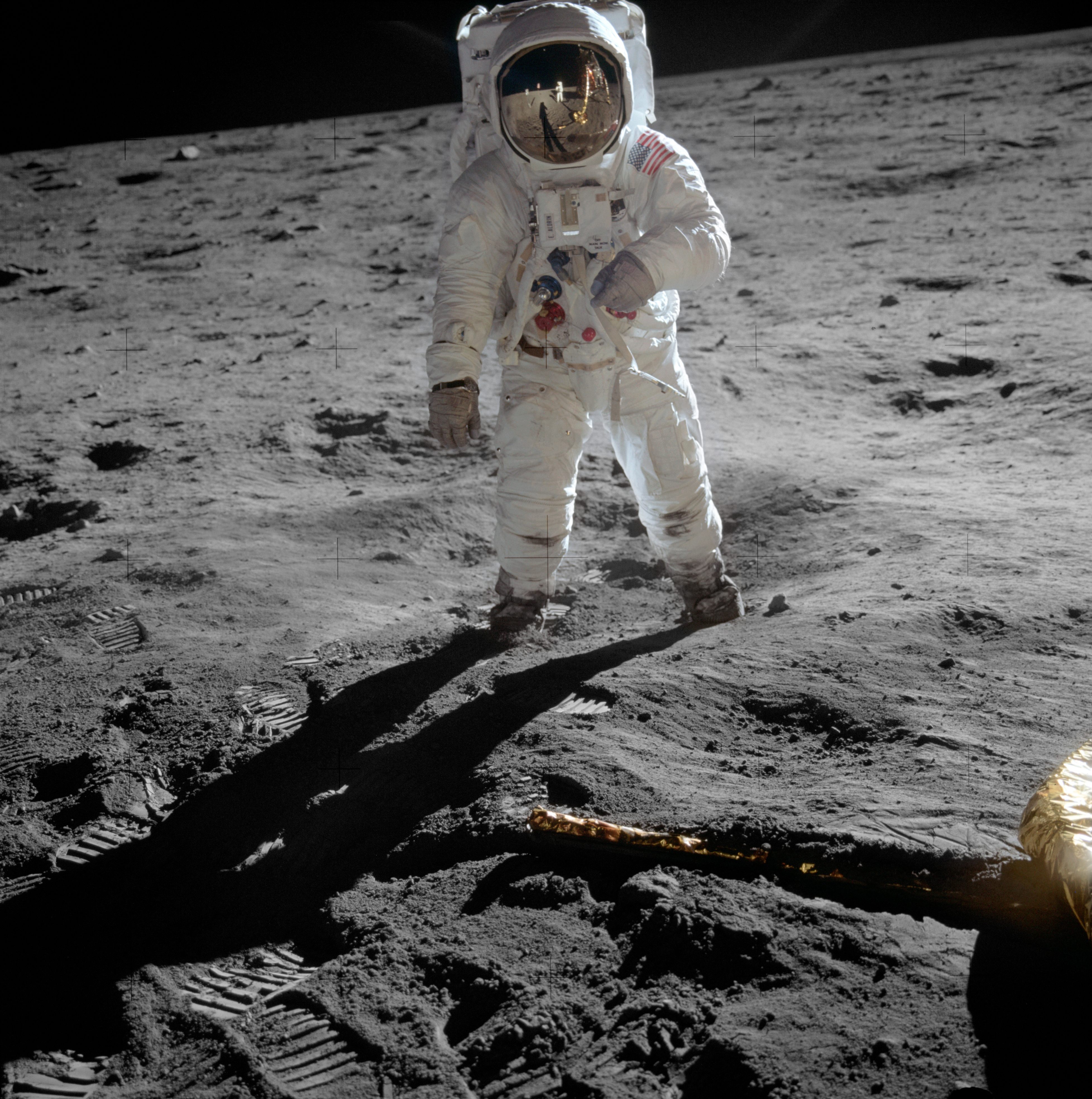

Its companion, Trip to the Moon, charts a potential route for the astronauts Michael Collins, Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin, with the “bug-like” lunar lander touching down close to the Ocean of Storms, one of five potential landing sites identified by the Apollo 11 press kit that NASA released on July 6.

Unlike the typical Esso road map, or the pictorial maps Standard Oil also distributed for kids in the backseat, Map of the Moon and Trip to the Moon are printed single sided. Instead of the much more economical recto-verso combination, each has a completely blank back. Their physicality anticipates collection and display, rather than use in the car, and their visual style appeals to either a child’s bedroom or a parent’s den. (Today, collectors might pay hundreds for the former freebies.)

While the red, white, and blue of Esso’s (or Humble’s) logo is prominent on the maps, American patriotism is virtually non-existent. An inset photograph on Trip to the Moon shows “USA” stamped on a Saturn V rocket, and includes a small NASA credit, but nowhere else does it mention the United States or the space agency by name, although the word “astronaut” subtly reminds viewers this will not be a Russian cosmonaut mission.*

Similarly, Map of the Moon eschews the nationalistic rhetoric of the Space Race and instead notes the Soviet Union’s “historic feat” of photographing the far side of the moon, in October 1959. The place names Moscow Sea and Tsiolkovsky reinforce Russia’s role in lunar exploration. Though it does credit the U.S. Air Force for providing the map’s base photo mosaic, it makes no reference to NASA. Instead, it encourages users to “use this chart to follow the news of future moon missions as the second phase unfolds and actual landings and exploration are made by man”—implicitly landings and exploration made by men of any nation.

With unexpected patriotic restraint, Map of the Moon and Trip to the Moon speak to the universal appeal of the lunar landing—a watershed event that would attract a global television audience of 600 million. (Capitalizing on that appeal, after the Apollo 11 astronauts splashed down in the North Pacific Ocean, Hammond Incorporated published a “talking” version of Trip to the Moon, complete with photographs from the mission and a 14-minute record custom-pressed by MGM.)

If Map of the Moon and Trip to the Moon downplay America’s lead in the Space Race, two other handouts would have left no doubt among gas station regulars of America’s winning space program. Also designed by Hammond and distributed by Esso and Humble, The Solar System and America’s Space Flight Program chronicle by name the “elaborate” accomplishments of NASA’s Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, while anticipating “the Mars Excursion Module” that will take both astronauts and, no doubt, American flags into the great beyond.

*Correction: Previously, this article stated that no American flag was present in Trip to the Moon. However, there is one visible in the panel labeled 9.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook