For Centuries, People Took Chunks of Stonehenge Home as Souvenirs

During the Victorian era, such behavior was not only common but expected.

In 1860, a concerned tourist wrote to the London Times decrying the “foolish, vulgar and ruthless practice of the majority of visitors” to Stonehenge “of breaking off portions of it as keepsakes.” Today, taking a hammer and chisel to a Neolithic monument seems like obvious vandalism, but during the Victorian era, such behavior was not only common but expected.

English antiquarian tourists, who were mostly upper class, had developed the habit of taking makeshift relics from the historical sites they visited during the 18th century. By 1830, the practice was so widespread that the English painter Benjamin Robert Haydon dubbed it “the English disease,” writing, “On every English chimney piece, you will see a bit of the real Pyramids, a bit of Stonehenge! […] You can’t admit the English into your gardens but they will strip your trees, cut their names on your statues, eat your fruit, & stuff their pockets with bits for their musaeums.”

For centuries, both locals and visitors had taken pieces of Stonehenge for use in folk remedies. As early as the 12th century, rumors of the stones’ healing properties appear in the writing of Geoffrey of Monmouth, and in 1707, Reverend James Brome wrote that their scrapings were still thought to “heal any green Wound, or old Sore.” In the 1660s, the English antiquarian John Aubrey reported a local superstition that “pieces or powder of these stones, putt into their wells, doe drive away the Toades.”

Eventually, tourists were not just taking from Stonehenge, but also leaving their mark, too. By the middle of the 17th century, tourist graffiti was appearing on the stones. The name of Johannes Ludovicus de Ferre—abbreviated “IOH : LVD : DEFERRE”—is etched, and so is the engraving “I WREN,” which may refer to Christopher Wren, the famed architect who designed St. Paul’s Cathedral.

As early as 1740, the archaeologist William Stukeley was decrying “the unaccountable folly of mankind in breaking pieces off [the stones] with great hammers,” and by the end of the 19th century, according an 1886 commenter, “Almost every day takes some fragment from the ruins, or adds something to the network of scrawling with which the surface of the stone is defaced.”

In his book Stranded in the Present, the historian Peter Fritzsche has argued that, in the wake of the French Revolution and in the face of increasing industrialization, Europeans stopped seeing the past as a reliable guide to the future. As the world became more and more unrecognizable, they felt disconnected from what had gone before. Fritzche writes, “The past was conceived more and more as something bygone and lost, and also strange and mysterious, and although partially accessible, always remote.”

For English tourists traveling to historical sites, taking a piece of the place as a souvenir offered a tangible link to this disappearing past. Also, breaking off a piece of prehistoric stone, or carving one’s name into it, altered the historical landmark, physically leaving one’s imprint on history.

In her book The Discovery of Britain: The English Tourists, 1540–1840, the historian Esther Moir writes that “all” 18th-century English upper-class tourists “recounted the triumphs they enjoyed in securing trophies on their travels, whether they came by them by honest means, by craft, or by outright theft.” The building of railroads in the early 19th century made domestic travel more accessible to the middle and working classes, and as more Britons began to travel, greater numbers of tourists plundered historical sites.

Stonehenge became easier to visit in 1847, when the railroad was extended to nearby Salisbury, and even easier when a direct line from London opened ten years later. The increased vandalism that went hand-in-hand with increased tourism became a topic of public discussion beginning in 1860, thanks the aforementioned letter printed in the London Times. The anonymous writer reported that, during a visit to Stonehenge some years prior, he had seen “an old lame man” from the nearby town of Amesbury, who would sell tourists pieces of the stones “which he had barbarously knocked off.” But another letter, printed three days later, defended the man, arguing that he was the monument’s caretaker, and that he actually deterred vandals, in part by selling alternate souvenirs.

Stonehenge had long had a caretaker, but this was a self-appointed, unpaid role, according to the archaeologist Christopher Chippindale. In 1822, an itinerant lecturer named Henry Browne arrived in Amesbury to give a series of talks on ancient history. He became so fascinated by the stone circle—he believed it pre-dated Noah’s flood—that he installed himself as the self-identified “first custodian of Stonehenge.” After his death in 1839, his son, Joseph, took up the role. But since the custodial position offered no salary, each man had to hustle to make the job worth his while. Henry Browne wrote and sold guidebooks, while his son hawked paintings and plaster miniatures of Stonehenge out of a wheeled contraption one visitor described as “half-wheelbarrow half-peepshow.” Joseph Browne’s successor, a photographer named William Judd, did a brisk trade taking photographs of tourists, then developing them in his mobile darkroom, which was stationed near the stones and pulled by a white horse.

Naturally, these self-appointed guardians were more concerned with earning tips by holding visitors’ horses or lecturing to them on Stonehenge’s history than they were with protecting the stones. Moreover, at the end of the 19th century, the custodian’s day off was Sunday, perhaps the busiest day of the week for visitors. According to an 1886 report on the state of the monument by the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, “There was a caretaker, but there was very little evidence of any care being taken.”

Stonehenge was, at this point, privately owned. Aside from one reference to “the way leading to Stonehenge” in a 1379 claim for access rights, medieval records don’t mention the stone circle at all, but we know that from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066, when it seems to have belonged to William the Conqueror, Stonehenge passed through the hands of various noble families, until the land was sold around 1628 to Sir Lawrence Washington of Garsdon, an ancestor of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Over the next 200 years, several other aristocratic families had possession of the site, until it was purchased by Sir Edmund Antrobus, 1st Baronet, in 1824.

In 1871, The Times published another series of letters regarding the state of Stonehenge, initiated by a writer who signed off as “A Vacation Rambler.” “There were many visitors,” the Rambler wrote of a recent visit to the site, “and a constant chipping of stone broke the solitude of the place.” The monument’s owner, Edmund Antrobus, 3rd Baronet, retorted in a published response a week later that “considering the thousands who annually visit it, I think the public deserve much credit for the very little damage done.” Antrobus did report several disturbing tales of vandalism, however, including an exchange with a “respectable paterfamilias,” who, upon being asked by Antrobus not to use his hammer and chisel, shot back, “And who the deuce are you, sir?” Told that Antrobus was the owner, the man responded that he believed the stones to be “public property.”

Though privately owned, Stonehenge was, at this point, part of a national conversation regarding the government’s role in sites of historical import. The 1882 Ancient Monuments Act offered government support to protect and restore designated sites—Stonehenge among them—but made it voluntary for owners to submit their property to government guardianship. Sir Edmund Antrobus, 3rd Baronet, lobbied against the act in Parliament, and refused to cede control over Stonehenge to the Commissioners of Works, who would oversee the site as designated under the act.

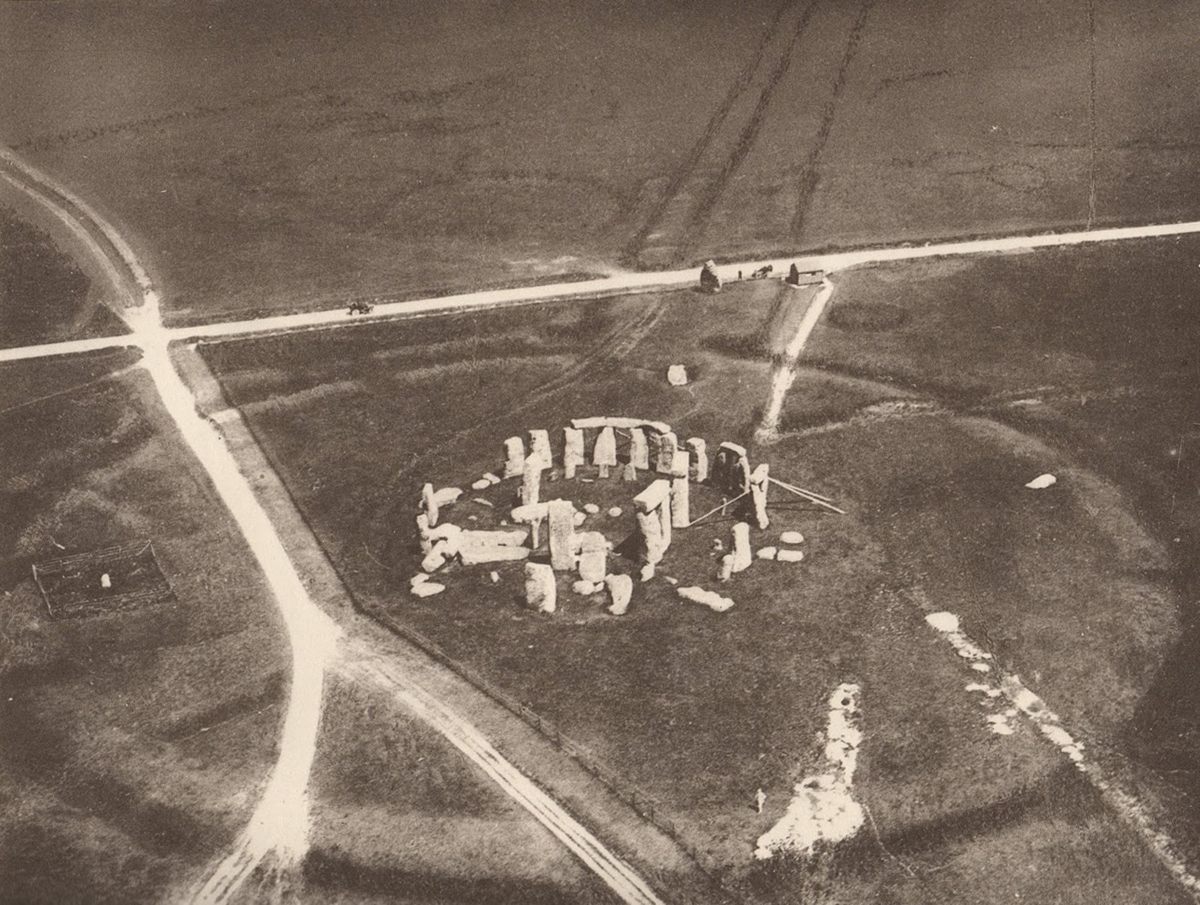

The 3rd Baronet died in 1899, and his son, Edmund Antrobus, 4th Baronet, assumed control of Stonehenge. The next year, two of Stonehenge’s sarsen stones collapsed, causing much concern in the newspapers that the monument was in a dire condition. In 1901, the 4th Baronet constructed a barbed-wire fence around the stone circle and began charging a shilling per person for admission.

This fence proved hugely controversial. Photography magazines debated the extent to which the barbed wire obstructed the photographic view of the stones, while a group of archaeologists protested the “artistic” destruction it had wrought. Members of a group advocating for public access to land even sued Antrobus, but the court dismissed the suit.

Antrobus argued that the fence was necessary to protect the stones, and the entrance fee justified by the cost of paying two new custodians to watch over the site. He had another reason for putting up barbed wire, though: He wanted to sell Stonehenge to the government. Antrobus offered the monument for the princely sum of £125,000, threatening that if the government declined to purchase it, he would be forced to “sell the stones to some American millionaire, who would ship them across the Atlantic.” Still, the Chancellor of the Exchequer rejected his offer. Antrobus lowered the price to £50,000, but the government refused to spend more than £10,000, so the monument remained in the baronet’s hands.

In 1915, the 4th Baronet died and the estate containing Stonehenge passed to his younger brother, Cosmo, who divided it up and sold it at auction. A local barrister named Cecil Chubb purchased the triangular section containing the stone circle for £6,600 “on a whim,” he said, as a present for his wife. (She was reportedly less than pleased, as he was supposed to be buying a set of curtains.) Three years later, the Chubbs gave the monument to the nation, stipulating in their deed of gift that the public retain “free access” and that visitors not be charged more than a shilling for admission.

The entrance fee has increased significantly over the ensuing century (currently, it’s £17.50 for an adult, if you book in advance), and while the public can still visit the stones, defacing them in any way is now a criminal act, rather than a routine and accepted occurrence.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook