In 1893, a Swedish Playwright Thought He’d Captured the Stars

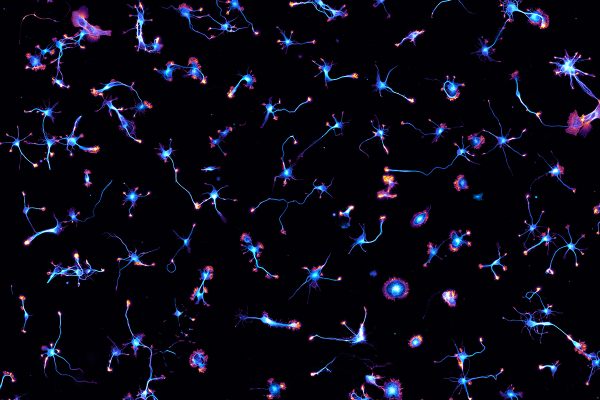

August Strindberg’s failed photography experiment continued to evolve, chemically and beautifully, long after his death.

August Strindberg wanted to get closer to reality. The storied 19th-century Swedish playwright, essayist, poet, and painter was also an avid photographer, but he refused to use lenses. He even dismissed the ones in human eyes, on the grounds that they distort the “real” world. So in the interest of taking lens-free photos, he began fiddling with photograms and pinhole cameras. But even that wasn’t enough. He needed something more immediate.

On a crisp winter day in 1893, Strindberg took a number of photographic plates into the Austrian night, outside the village of Dornach, and laid them under the stars in a tub filled with developer, so that he could capture the heavens. To everyone but Strindberg, it went terribly.

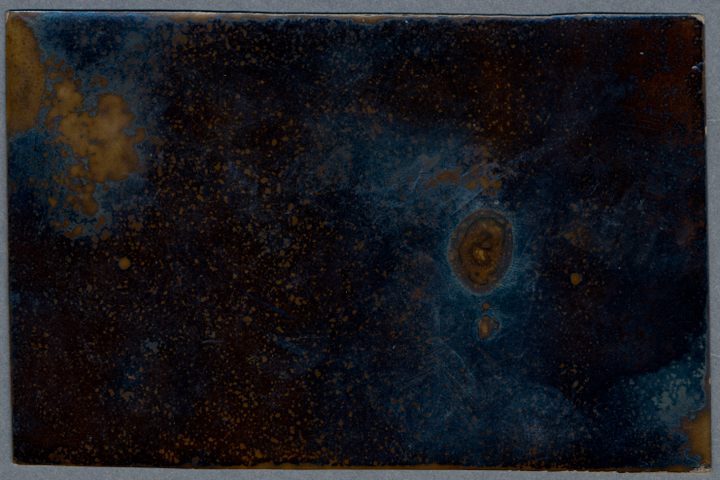

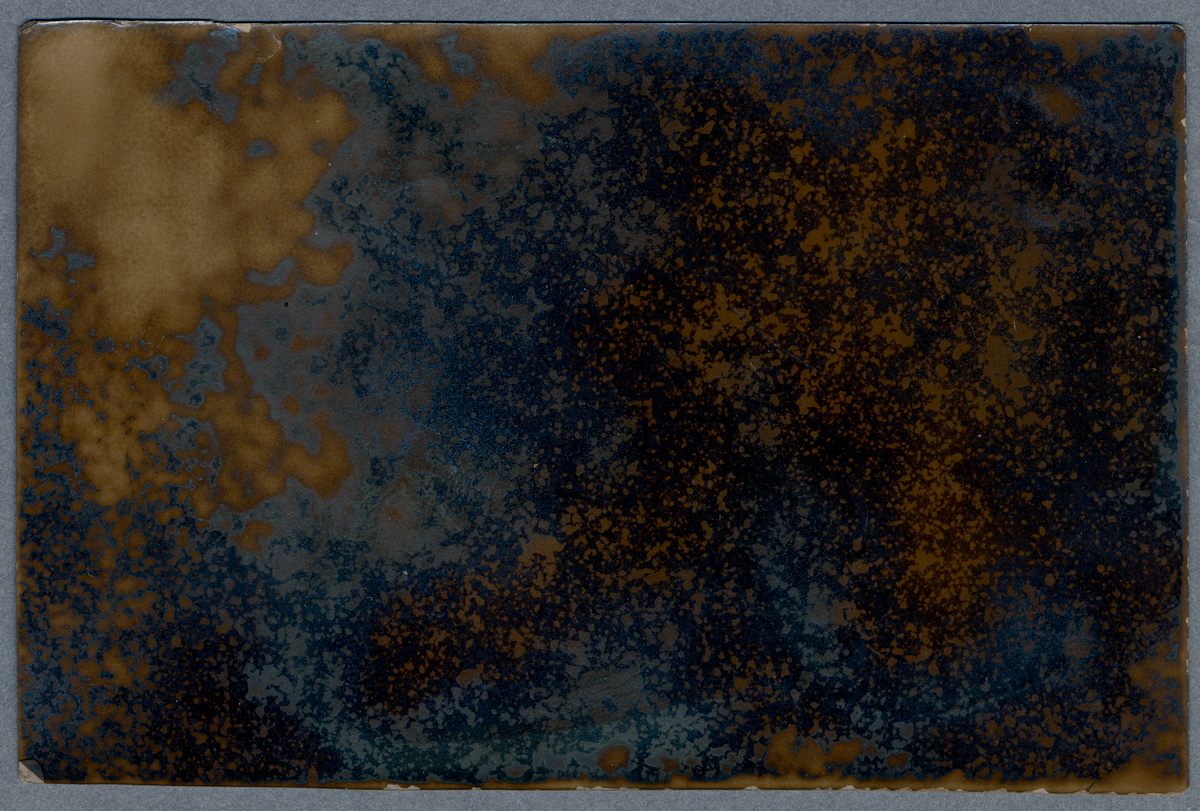

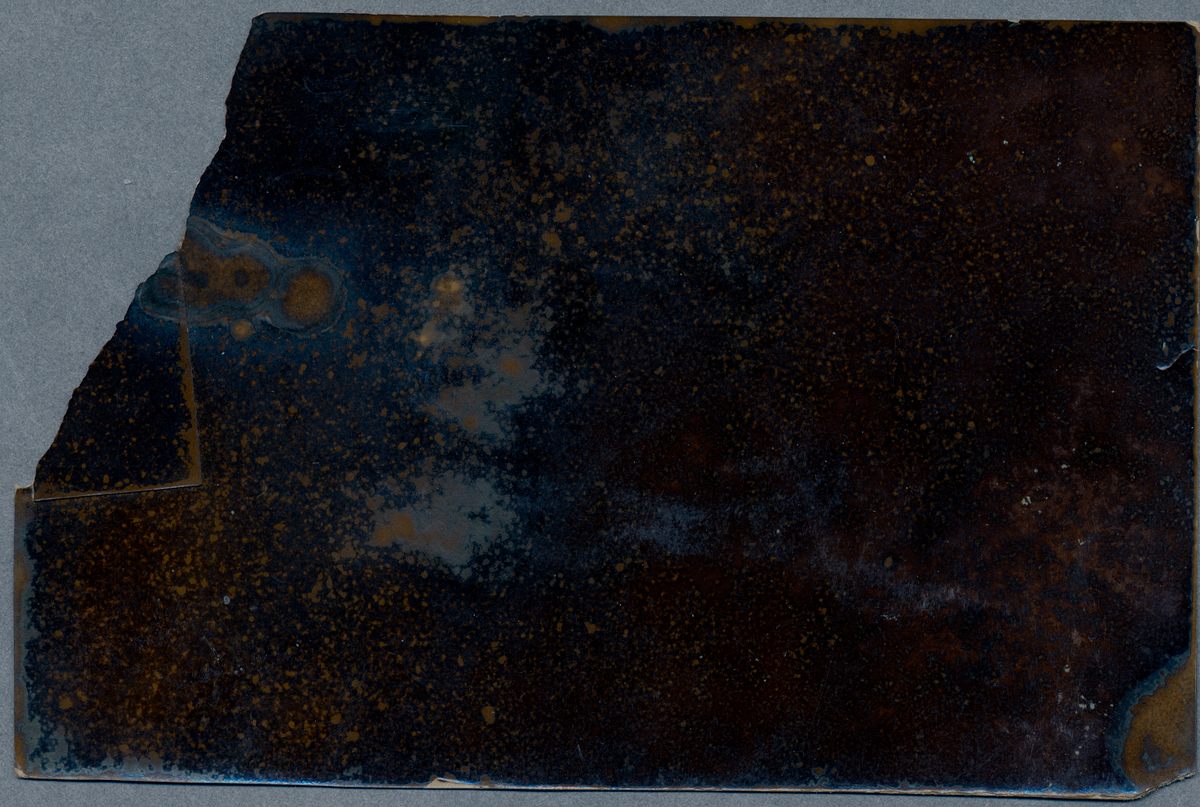

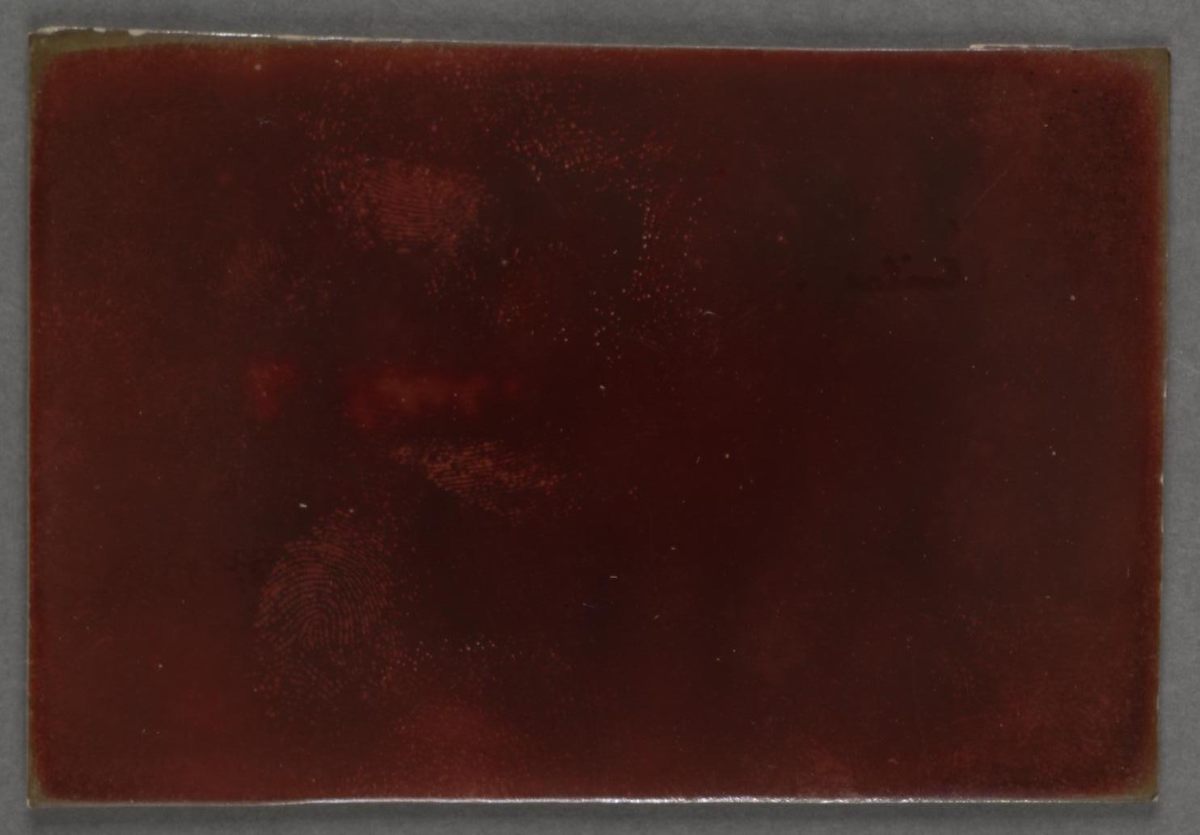

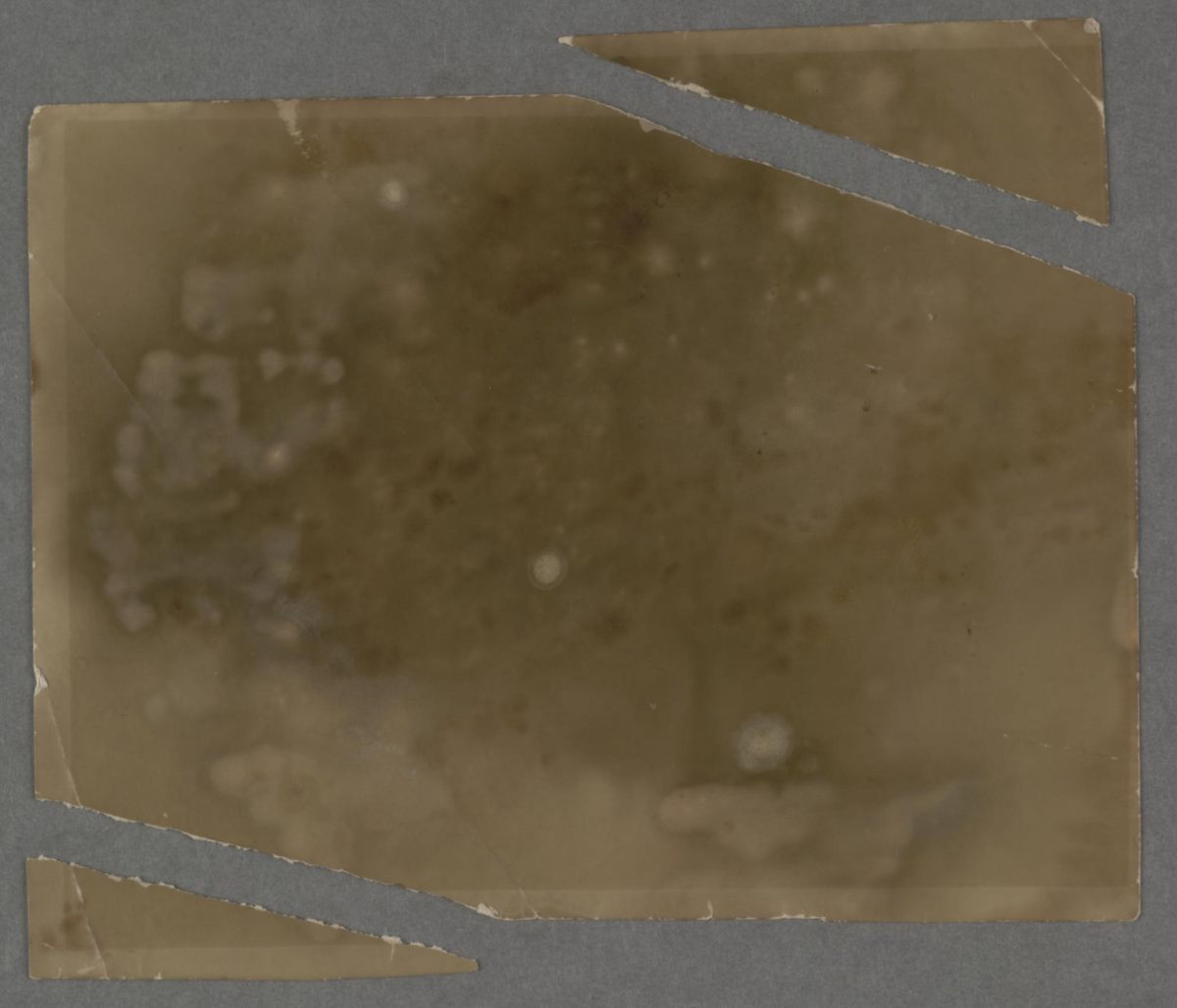

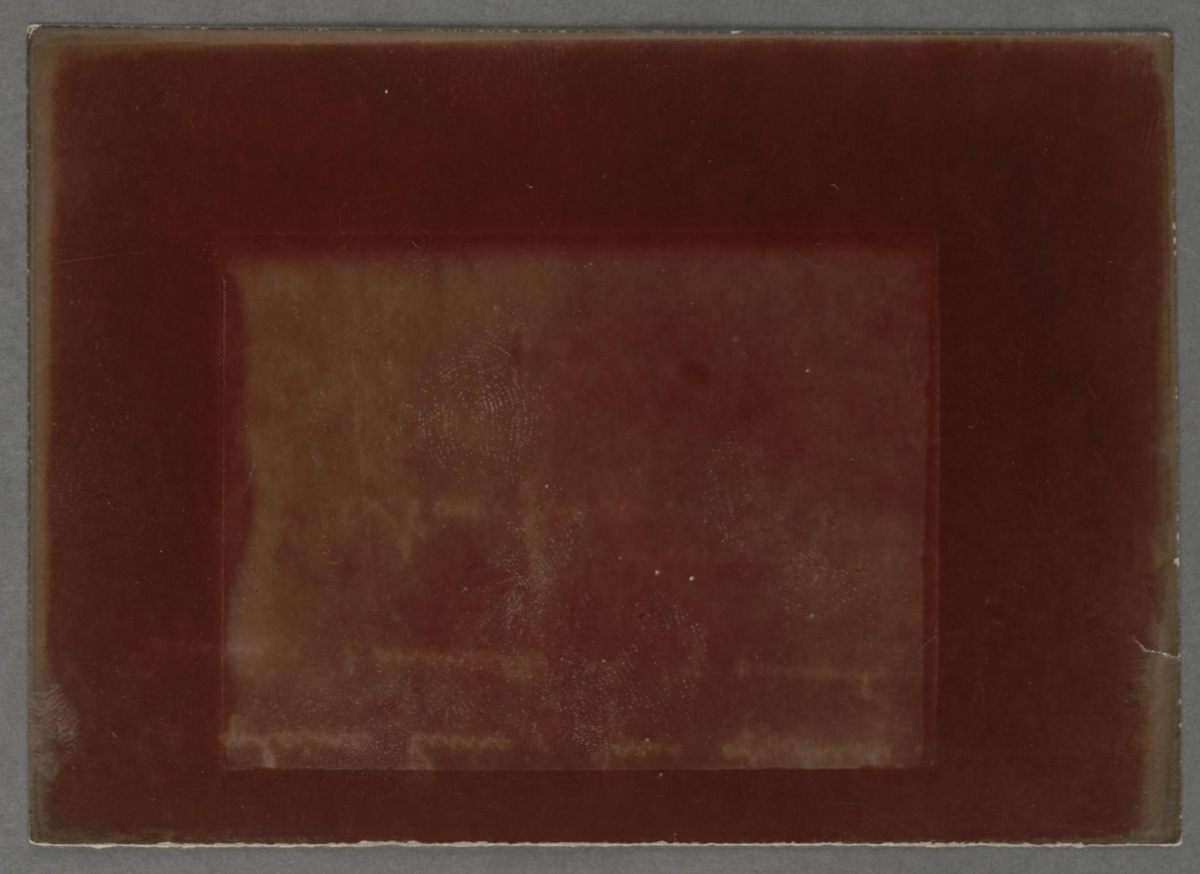

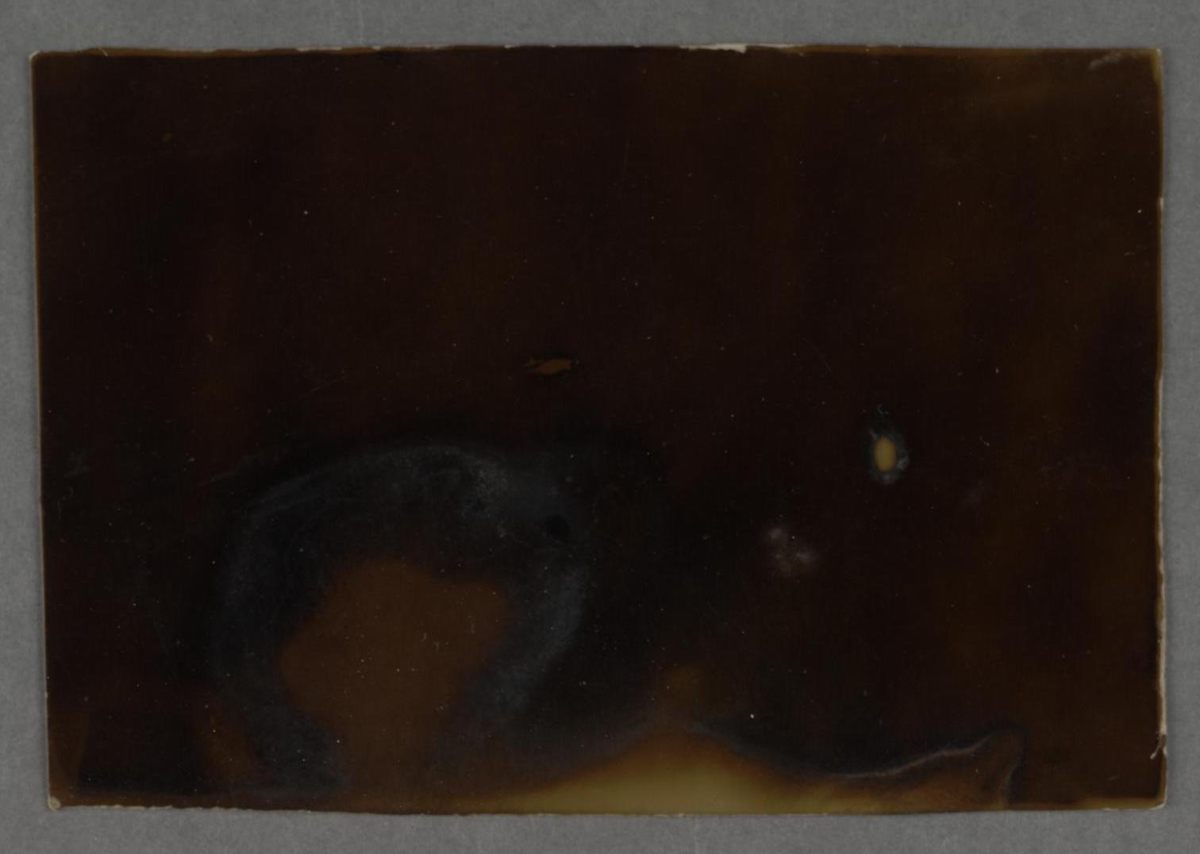

His attempt at a new photographic medium, which he called a celestograph, is actually a chemigram—an image created when chemicals react with photosensitive material. The cloudy, particulate-speckled exposures were awesome to Strindberg, who thought he’d captured the starry skies in all their galaxy-laden, supernova-infused splendor. (To the unfamiliar eye, the celestographs resemble very moldy cheese, or Mark Rothko paintings. They are dark, liminal, and soft.)

The amateur astronomer wrote to a friend, “I have worked like a devil and have traced the movements of the moon and the real appearance of the firmament on a laid-out photographic plate, independent from our misleading eye.”

Though he was wrong, and the project stalled after just 16 celestographs, Strindberg remained sure he was right up until his death, in 1912.

Yet his celestographs continued to evolve, as the photoreactive plates accrued exposure in the years after they were placed in the archives of Sweden’s Nordic Museum and, later, the National Library of Sweden.

As Douglas Feuk wrote in the journal Cabinet, ink stains—perhaps from a burst pen in some archival drawer—chemically altered the plates and left dark blotches on them. An unseen hand touched them as well, at some point after Strindberg’s death, leaving ghostly fingerprints on one of the celestographs, and adding a surreal touch to the artwork. The compositions—originally crafted under the sky, to mirror it—also reflected their journey through the decades.

Though the actual celestograph plates have disappeared—in museums, objects can sometimes hide in plain sight, or vanish altogether—a collection of these faux-astral exposures remain part of the National Library of Sweden’s online library. These are a few of them.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook