How a Banana-Chicken Casserole Defined Swedish Cuisine

The recipe for “Flying Jacob” was the improvised creation of an air-freight worker.

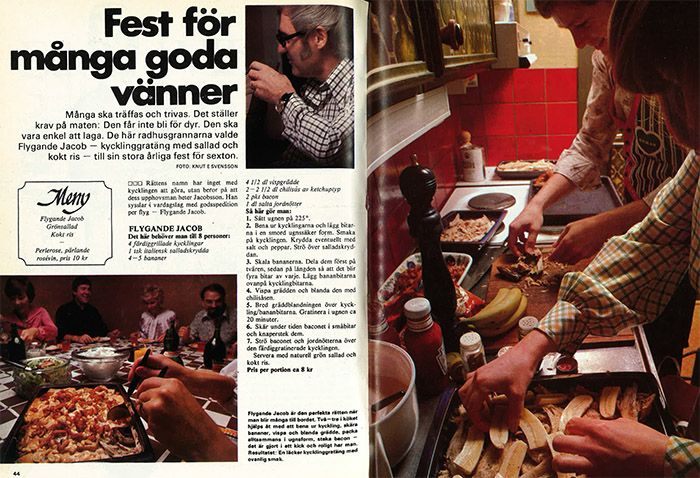

In his best-selling Nordic Cookbook, internationally renowned chef Magnus Nilsson praises the Flying Jacob, writing that “few dishes are as emblematic and unique to the contemporary food culture of Sweden.” The original recipe calls for shredded, grilled chicken topped with sliced bananas and Italian salad spice to be submerged in a mixture of whipped cream and Heinz chili sauce. After baking, it’s to be sprinkled with fried bacon chunks and peanuts—an unusual combination of ingredients that’s been called “anti-epicurean,” and “a truly horrifying mash-up of things.”

Swedes beg to differ. In the nearly half-century since its inception, the casserole has become ubiquitous. Peaking in popularity through the 1980s, it’s still served in cafeterias and nursing homes, sold as a frozen meal, and offered as a baby-food flavor. And it’s not a one-off—the popularity of Flying Jacob reflects a uniquely Swedish sensibility toward food.

The story goes that in the summer of 1976, air-freight worker Ove Jacobsson was woefully unprepared for a neighborhood dinner party. He rummaged through his kitchen, threw what he found in the oven, and created the first Flying Jacob. The dish was a hit among his neighbors, including Anders Tunberg, then an editor of Allt om Mat, or “All About Food.” Tunberg gave the dish its nickname, Flygande Jakob, an allusion to Jacobsson’s occupation and last name, but also a reference to a Swedish long-distance runner from the 1940s. (Other accounts credit Jacobsson with coining the name.) With Tunberg’s encouragement, Jacobsson submitted the recipe to his magazine.

In their September, 1976 issue, the magazine pitched the salty-sweet, creamy-crunchy hodgepodge as the perfect party casserole, one that’s “easy to make and tastes great.” It was an overnight sensation, a simple solution to working families’ weeknight hunger, comprised of affordable ingredients.

The Flying Jacob’s flight path is a bit easier to understand in context. The 20th century in Sweden was a period of rapid modernization, creating a suburban middle class that enjoyed new luxuries: refrigerators, televisions, two-car garages, and exotic, foreign foods.

“As part of embracing this improvement in living standards, people abandoned traditional Swedish cuisine in favor of new and exotic ingredients and dishes,” remembers Swedish-born engineer Jonas Aman, “even if it meant making up completely ridiculous dishes!” The Flying Jacob emerged alongside other culinary oddballs such as kassler hawaii (a canned pineapple, curry, and cheese casserole) and After Eight Pears (baked preserved pears covered with mint chocolate).

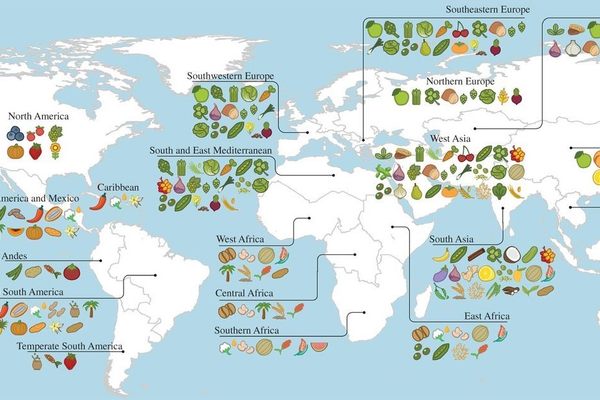

This newfound accessibility of foreign foods only highlighted a pre-existing Swedish propensity for mixing sweet and savory flavors. Sweden’s longtime national dish, meatballs, is often served with sweetened lingonberry jam, and as Dr. Richard Tellström, Professor of Food and Meal Sciences at the University of Stockholm, points out, “You can serve sweet jam [with] fried herring as well.” Similarly, a traditional Swedish Christmas lutefisk platter pairs lye-fermented cod with cranberries. It’s a testament to the uniqueness of Swedish taste that American author Garrison Keillor claimed, “Most lutefisk is not edible by normal people. It is reminiscent of the afterbirth of a dog.” Another sweet and savory recipe for a Swedish fish fillet called Spättabörsar med banan includes almond shavings, tomatoes, and sweet bananas.

“Swedes don’t compartmentalize foods too much,” says food writer John Duxbury, and especially not when it comes to bananas, a key ingredient in the Flying Jacob. Bananas accompany many of the country’s savory dishes. The similar flaskfile med banan is a casserole of pork, bananas, peppers, cream, and curry.

This Swedish culinary proclivity for bananas seems to have been encouraged almost as national policy. The fruit was one of the earliest tropical varieties to hit Swedish soil. The first shipment, in 1906, of two trucks carrying 200 bunches of bananas sold out in days. In 1914, a steamer carrying 10,000 kilograms of the fruit sold out in just a week. “It became a symbol of both the modern and international society,” says Dr. Tellström.

Following a wartime drought in imports, a boon of “heavy [banana] propaganda,” writes Swedish economic historian Rosalia Guerrero Cantarell, brought the fruit roaring back. Newspaper articles touted the fruit’s nutritional benefits for children and the elderly; banana-recipe contests offered handsome rewards. A book published by banana ad-man Axel Blomgren titled The Wonderful World of Bananas argued, for the sake of the country, that Swedes should consume more bananas to lower their price. Magazines and cookbooks published by advertisers flooded readers with opinion articles, banana anecdotes, and recipes, including a banana, celery, lemon, and white pepper salad recommended to accompany grilled meats. In 1916 an argument sheltering bananas from all import customs received broad support in Parliament; from 1916 to 1933, the fruit was customs free. As of 2010, Cantarell notes, banana consumption in Sweden handily topped national averages across both the E.U. and the U.S.

This embrace of new arrivals over traditional Swedish fare intensified in the 1960s. After abstaining from the World Wars and the Cold War, Dr. Tellström says, “We had a longing for international cultural context.” The international student protests of 1968, then, gave the neutral country an opportunity to participate in a global cultural shift. Food writers and journalists of the day encouraged Swedes to ditch pretension and arrange informal, communal dinners in their newly outfitted suburbs. The Flying Jacob was an easy casserole to make for these gatherings. “It was easier to serve brand new dishes which had no older customs attached to it,” adds Dr. Tellström. And what had fewer customs attached to it than Ove Jacobsson’s banana-chicken casserole?

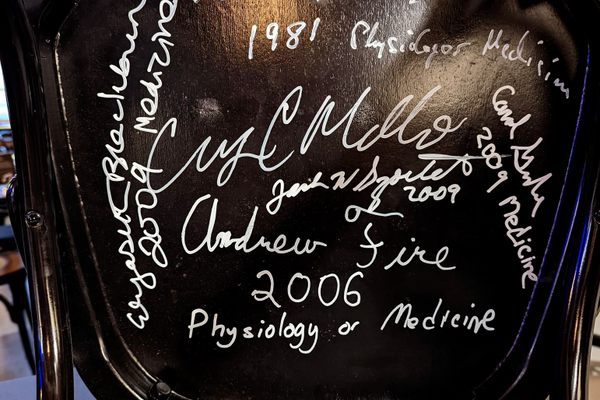

In 2014, Allt om Mat caved to widespread reader demand and reissued the original recipe, prompting its inventor to break from decades of silence to marvel at his contribution. “I never thought [my] recipe would have this impact,” he wrote in the comments section. “[It’s] my contribution to the dinner tables and lunch restaurants around the country.” The magazine’s current editor, Charlotte Jenkinson, told The Takeout that the recipe is still referenced daily, and most Swedish households have developed their own versions.

While its popularity has long since peaked, visitors to Sweden can still track it down in small restaurants and cafeterias. And if that doesn’t sound appealing to you, you should know that most foreigners who express dismay at the ingredient list go on to praise Flying Jacob once they’ve tried it, confessing shame over their previous reservations or complimenting the brilliant pairing of sweet bananas, Italian spice, and smoky bacon fat. If you plan to cook it at home on your own, Dr. Tellström advises, “it must be Heinz chili sauce.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook