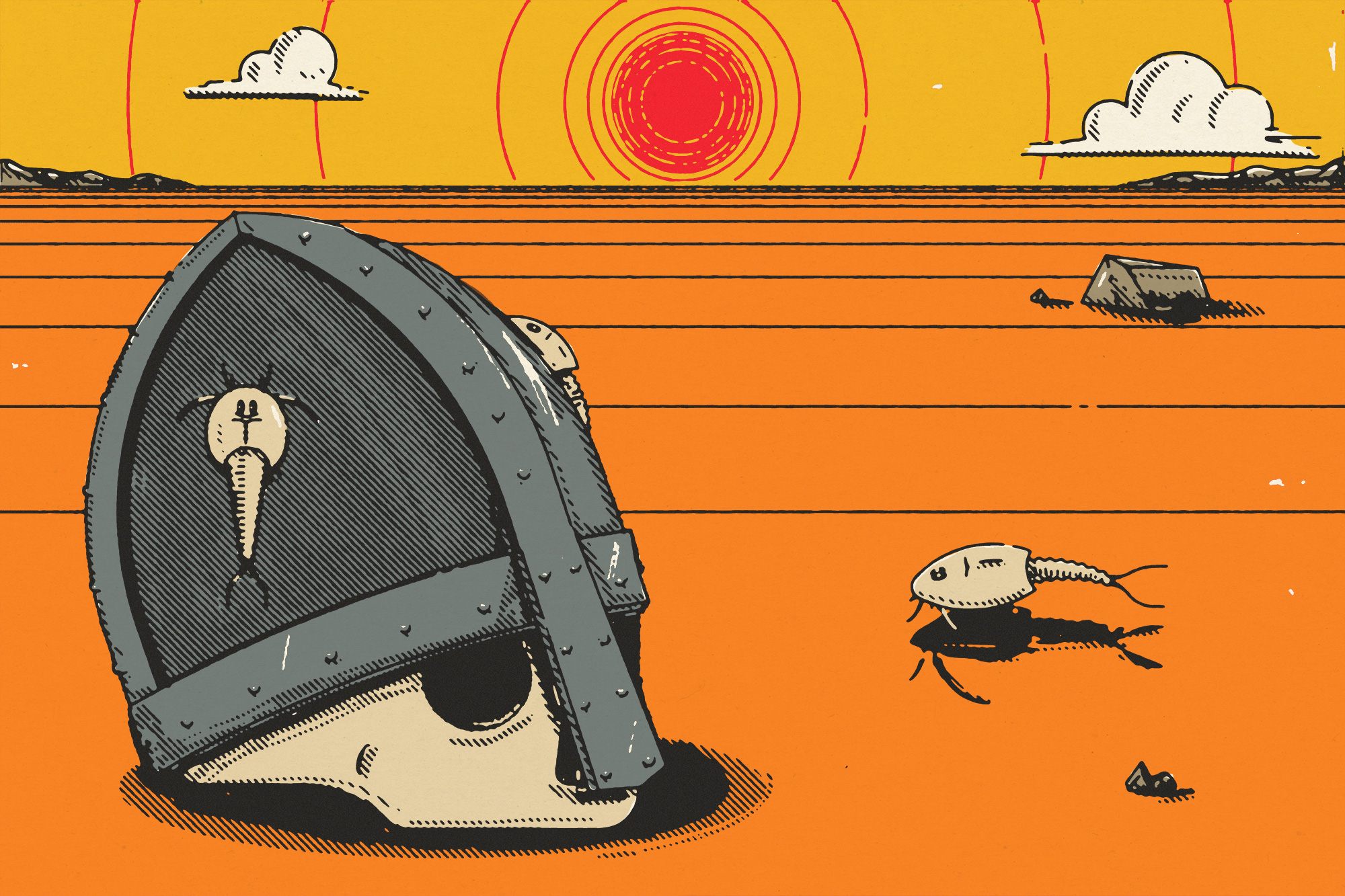

These Tiny Desert-Dwelling Crustaceans Are Incredibly Patient

Tadpole shrimp hunker down, waiting for water conditions to be just right.

How do animals survive in harsh environments? This week, we’re celebrating some extreme desert-dwellers. Previously: the worm lizard that beats the heat by never coming to the surface, the beetles that capture the fog in the Namib, the penguins of Antarctica’s cold deserts, and the horned viper that hides beneath the sand.

Across the orange, ruddy, desert of the Colorado Plateau—which includes portions of Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico in the southwestern United States—summers are dry and sweltering, with upper temperatures closing in on 140 degrees Fahrenheit.

Tadpole shrimp find a way to make it work.

These small crustaceans are armored and tiny; they look like itty bitty horseshoe crabs. They’re widely considered to be among the most ancient species on the planet, having appeared millions of years ago. They love the water—and in the desert, that can be hard to come by.

Scattered around the landscape, the adults find water wherever they can, according to the National Park Service, including making the best of potholes or ephemeral pools that fill seasonally. (This behavior is known as “escaping” a drought.) The murky water may not be anything to write home about, but it’ll do the job.

Their eggs are tough, too. They are capable of withstanding anhydrobiosis, a process of nearly complete desiccation, according to the NASA Astrobiology Institute. Many species manage this by producing trehalose—a type of sugar—to stand in for water, and keep the creature’s shape. Tim Graham, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, told NASA that some tadpole shrimp eggs had stuck around for decades. “Eggs of tadpole shrimp or fairy shrimp have been kept for 50 years in the lab, and were still viable,” Graham said.

When the eggs do hatch, the young shrimp in their cozy, watery potholes do a lot in just a little bit of time. To put it bluntly: They gorge, and then they get busy. “With remarkable speed, eating about 40 percent of its own body weight each day, the tadpole shrimp grows to maturity in two to three weeks,” The Guardian once reported. (Other reports say the maturation process is even swifter.) “This enables it to lay another lot of eggs before its home dries out again,” The Guardian continued. Those offspring will remain dormant until conditions are right. The shrimp are no more than a few inches long, but they punch way above their weight, and hang in there like champs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook