Stitching a Future for an Age-Old Palestinian Embroidery Tradition

Wafa Ghnaim is introducing people to “tatreez” through her workshops.

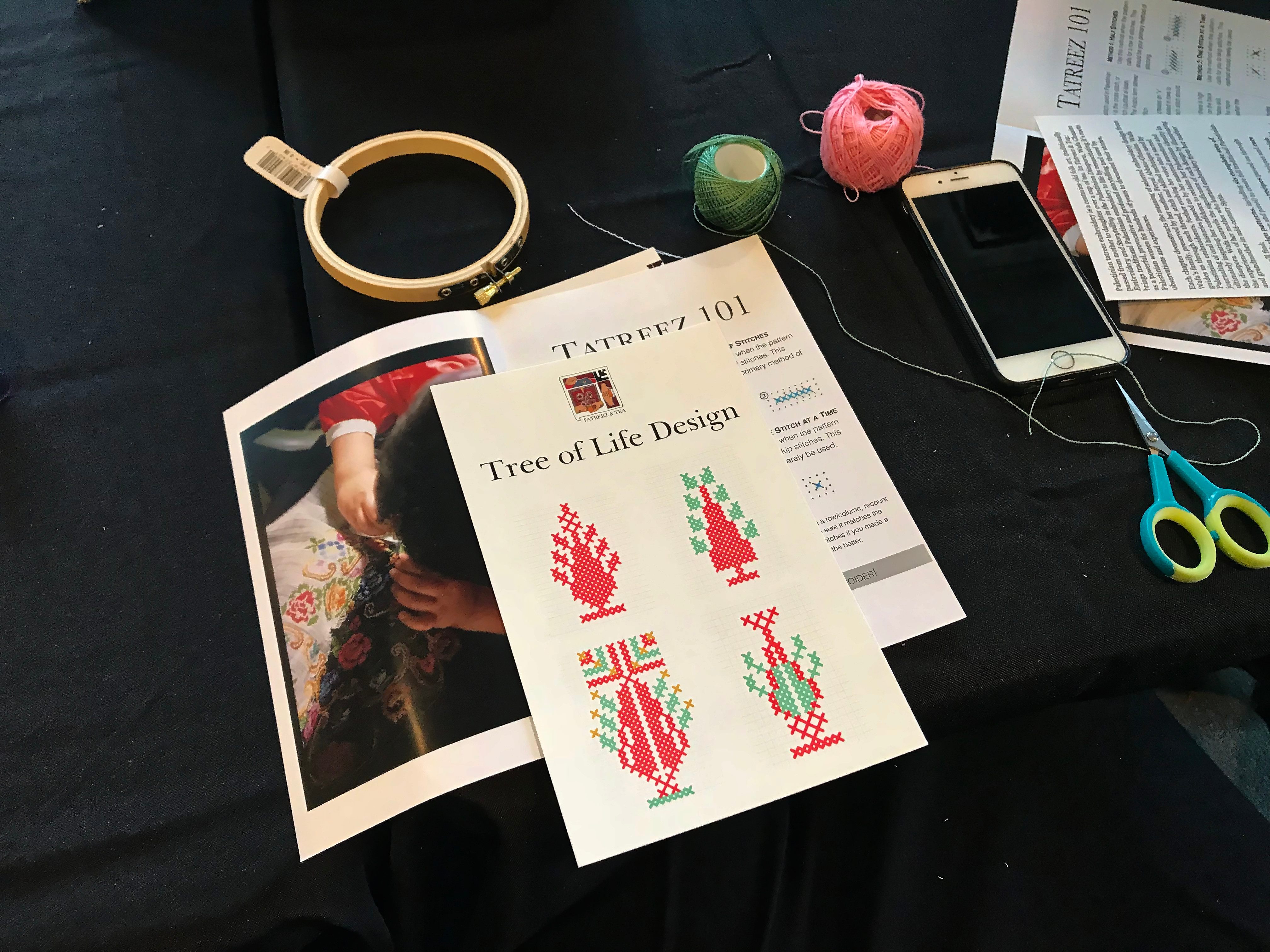

In a big-windowed lecture room, Wafa Ghnaim, author of a self-published book on Palestinian embroidery (known as tatreez) and founder of the nonprofit teaching initiative Taztreez & Tea, kicks off a three-hour needlework workshop with a heated primer on the perfect cross-stitch.

“Palestinians, we have a way for everything, even cutting our bread,” the 35-year-old entrepreneur, dressed in an intricate, hand-threaded maxi skirt, explains.

Whereas Japanese needlework, for example, focuses “on the way each stitch lays on top of each other,” Ghnaim says, Palestinian embroidery emphasizes the “cleanliness on the back of the cloth” and the ability to make out the motif on both sides. Eventually, she assures the class, “you’ll have a clear front and back.”

At least, that’s the goal. The larger mission of Ghnaim’s workshops, lectures, and publications—produced with backing from the Brooklyn Arts Council—is to revitalize the art of Palestinian embroidery, reaching new fans in the diaspora.

Ghnaim, who was born and raised in Oregon, is the daughter of the acclaimed embroiderer Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim, the 2018 recipient of a National Heritage award fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts (“She even got a letter from Donald Trump,” chuckles Ghnaim. “He didn’t look that [her work] was Palestinian.”) She grew up apprenticing for her mother, who in 1948 fled war-torn Safad, now a town in present-day northern Israel.

The age-old craft of tatreez, a folk art practiced by rural women for centuries, serves as a window into the history of Palestinian exile. Mothers and grandmothers used to pass down designs, with different motifs associated with each village. After the founding of Israel in 1948, 750,000 Palestinian residents—roughly half the population—were forced into exile, an event remembered in Arabic as the Nakba, or catastrophe. Another disruption took place in 1967 during the Six-Day War—known as the Naksa, or defeat—when Israeli forces first occupied the West Bank. Basic survival superseded the role of craft traditions and place-based practices were upended.

“When Palestinians were exiled in 1948 and 1967, they weren’t carrying a pattern book. They were carrying their baby and running out the door,” Ghnaim says.

Yet in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, refugee camps also became vehicles of exchange as communities from all over Palestine converged. “There was a lot of sharing,” adds Ghnaim, as together women “had to recall and recreate their motifs.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) revived folk traditions to promote Palestinian national heritage. According to Rachel Dedman, a London-based art critic who curated a show on the political history of Palestinian embroidery, tatreez became “a key signifier” of “endurance in the face of Israeli erasure and violence.” By the late 1980s, when the First Intifada erupted, embroidery emerged as a potent expression of resistance. The traditionally feminine craft spread as Palestinian men, languishing under Israeli lock-up, began honing their skills, explains Dedman.

In Ghnaim’s classes, men now typically make up a modest portion of the attendees. “I think that gendered aspect is breaking down, which is necessary for this art to stay alive,” she says. “I see in my classes a whole wide mix of people. I don’t just see Palestinian women and Palestinian men. I see non-Palestinian women. I see non-Palestinian men.”

Ghnaim’s educational events began running in Brooklyn and will soon move to Washington, D.C. On the day that I attend in October 2018, the pop-up is running alongside the D.C. Palestinian Film and Arts Festival, an annual lineup of Palestinian cultural offerings that features a richly embroidered tatreez design as its logo. Today, the assignment given to the 17 workshop attendees is to reproduce a delicate cypress motif, known as the “Tree of Life.”

The room grows quiet with concentration, and the afternoon passes quickly. Unlike other species, the cypress tree “stays green and survives,” explains Ghnaim. “It gives until it dies and that’s the purpose of life. You give until your last day.” In the time it takes me to throw together a few rows of practice cross-stitches, Razan Sahuri, a Jordanian-born nutritionist, has already shown off a tiny, pristinely-stitched cypress tree.

“I think most Palestinians, when we see the embroidery, it feels like home,” says Sahuri, who moved to D.C. three years ago from Dubai, and grew up feeling caught between cultures. “I’m Palestinian but I’ve never been to Palestine. When it’s so far away, you want a thread to hang onto your culture. Pun intended!”

Caught between home and exile, past and present, the meticulously crafted stitches seem almost suspended somewhere between time and space. Dedman, the London curator, explains that embroidery is “by nature labored, private, and slow.” Far from a spontaneous public expression, the time-intensive pieces nonetheless form a quieter form of protest, with an “extended temporality” that spans its own steady, thread-by-thread creation.

Sahuri finds comfort in this measured, repetitive motion. “It’s like meditation. You can’t think of anything else,” she says. “I don’t know if mind numbing is the right word?”

The scale on each piece is minuscule—each hole on the cloth just about the size of a period—and the work is eye-wateringly intensive. I have to pull apart my mangled tatreez stitches three times to start over. Though I had seen embroidered garments and souvenirs many times during my stays in Ramallah, it was only in attempting my own tatreez creation that I began to grasp the effort involved, as well as the complexity of each craft piece’s history. Embedded in each tatreez cloth are narratives of displacement and belonging, with embroiderers adding their own personal litany of sorrows and joys.

“Someone is really shedding skin when they’re producing the art,” says Ghnaim, who plans on pursuing a Ph.D. in Art History to trace the evolution of tatreez as it moves between generations in the diaspora. This year marks the re-release of an expanded print edition of her book: Tatreez & Tea: Embroidery and Storytelling in the Palestinian Diaspora. It also commemorates 70 long years of Palestinian exile.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook