The Counterintuitive History of Black Hats, White Hats, And Villains

Even in old Westerns, the white hat/black hat divide is less distinct than is often remembered.

In the first season of the hit TV show Westworld, a key character chooses to wear a white hat when he enters the western-themed park. Compared to his black-hatted companion, he starts out a gentleman: he doesn’t want to drink or sleep with a prostitute or randomly shoot the park’s robotic “hosts.” But (spoiler alert) over the course of his journey, his white hat becomes dirtied and dark, until, at a transformative moment, he switches it for a black hat.

This is some heavy-handed symbolism, but it’s supposed to harken back to a classic, familiar trope. This is a western, and in westerns, everyone knows, good guys wear white hats and bad guys wear black.

But even in the fictional American West, good and evil are not so clearcut, it turns out. Go digging into the history of black hats vs. white hats, and you’ll find that good guys wore black, bad guys wore white. “There is no trope or consistency in who wears white or black,” says Peter Stanfield, who’s studied the B-westerns of the 1930s. The black vs. white dichotomy was never quite so clean as it’s now remembered.

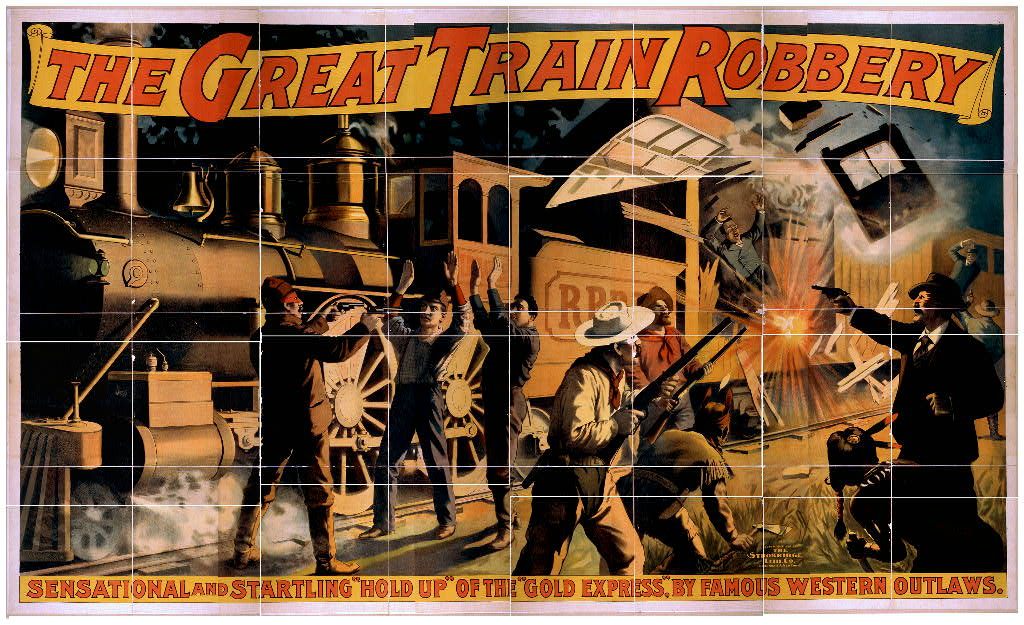

If there is a starting point of the idea that bad guys wear black hats, it’s at the very beginning of Western films. In 1903, Edwin S. Porter shot The Great Train Robbery in Milltown, New Jersey, far from the actual West. In the film’s twelve minutes, a group of gangsters hold up a bank, rob a train, and eventually receive their comeuppance. There’s no clear hat symbolism in the film; the gangsters all wear hats, some lighter than others.

But there’s one moment in The Great Train Robbery that’s more memorable than the rest—the moment at the end, where all of a sudden the camera clearly shows the face of one the gangsters, in close-up, pointing his gun at the audience. He shoots. One, two, six times. He’s wearing a black hat.

That moment became famous. The moment in the James Bond prologue, where he shoots directly at camera, takes inspiration from that shot; Goodfellas, Tombstone, and Breaking Bad all contain homages. But it’s harder to trace the influence of the black hat and harder still to find the first good guy to wear a white hat. “Out of all of the Westerns I have seen, there are very, very few of those movies where white hats are worn, either by good guys or bad guys,” says Kevin Stoehr, co-author of Ride, Boldly Ride: The Evolution of the American Western—perhaps because white cowboy hats weren’t particularly realistic. “You can imagine how dirty a white hat would have become in the dusty landscape.”

Of the film scholars I contacted, no one was able to say exactly where the idea that good guys wear white and bad guys wear black came from—there’s no influential movie that kicked off the convention. If it does have a starting point, it’s somewhere in the 1930s, when low-budget B-Westerns became part of Hollywood’s bread and butter. Tom Mix, one of the early Western stars, often (but not always) wore a white hat, and singing cowboys, including, most notably, Gene Autry, may have been more likely to wear them than other cowboys. Perhaps the most famous white-hat-wearing cowboy, the Lone Ranger, debuted on the radio during this decade and first rode onto the screen in 1938.

There are plenty of examples from Westerns film that do fit the white hat/black hat convention. Here, in Gangsters of the Frontier, for instance, a group of four bad guys comes in wielding guns; hero Tex Ritter, wearing a white hat, intervenes.

But there are also plenty of examples that don’t fit the convention. In that same scene, there’s a guy caught between the bad guys and Ritter who’s also wearing a dark hat, as a default. In John Ford’s 3 Bad Men, the villainous sheriff wears white, and the good-hearted outlaws wear black. In scenes of battles, there’s often a mix of lighter hats and darker hats, all fighting the same enemy. In a song from around the same time, Mississippi John Hurt sings of a character of ambiguous morality who kills a man for snatching the milk-white Stetson hat from his head. Roy Rogers often wore a white hat, but Eddie Dean, “the greatest cowboy singer of all time,” switched it up. Good guy Hopalong Cassidy wore dark clothes. In this golden age of Westerns, good and evil weren’t color coded: there was plenty of room for moral ambiguity.

Somewhere along the line, though, it became an accepted fact that good guys once wore white and bad guys once wore black. It’s always easy to imagine that the past was simpler, and modern films sometimes use white hat/black hat symbolism in a heavy-handed way, as an homage to this imagined past. In 3:10 to Yuma, for instance, Christian Bale’s good guy wears a white hat, while Russell Crowe’s bad guy wears a black one.

In this century, the black hat/white hat terminology is also used to delineate between people who break into computer networks with malicious or good intentions. That story is a little bit less clear cut than it seems, too. In early hacking circles, there was a whole separate term to refer to malicious hacking: those people were called crackers. Across the internet, Richard Stallman, who founded the GNU Project and Free Software Foundation, is often credited with coining the term “black hat” hacker, but he says that’s not correct.

“I have never used terms “X-hat hacker” because I reject the use of ‘hacking’ to refer to breaking security,” he says. Where did the term come from then? “I don’t know where,” he says.

On all fronts, it turns out, it’s not so simple to divide people into black and white.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook