The Criminal Origins of a Better Erection

In the 1920s, a prison doctor did some very bad things

Dr Leo Stanley with his wife, outside their residence at San Quentin Prison, c. 1915. (Photo: Courtesy Anne T. Kent California Room/Marin Country Free Library)

Prisoners have long been the subjects of exceedingly cruel scientific experimentation—infected with syphilis, the flu and cancer. But no experiments are quite as odd as the attempts to increase American masculine virility at the expense of incarcerated bodies.

In May 1928, 23-year-old Clarence “Buck” Kelly was hung in front of a large crowd at San Quentin State Prison in Northern California for shooting three people in the course of a drunken robbery spree.

After his death, as was routine, he was autopsied and, as was also routine for this particular doctor, Dr. Leo Stanley removed Kelly’s youthful testicles.

Dr. Leo Stanley was the chief surgeon at San Quentin between 1913 and 1941. During this time, he not only oversaw executions, but also conducted autopsies on the dead and, in some cases, removed their testicles to implant them into elderly residents of San Quentin. This is what he did with Kelly’s testicles. Dr. Stanley called the procedure “gland surgery.”

At the same time that Stanley was conducting his experiments, the penal system as a whole was experimenting with the “disease” model of crime. In a 1923 article, Dr. Stanley argued that crime came from one of three types of disease: moral, mental or physical. He based his conclusions on a wealth of materials gleaned from the required physicals when inmates entered San Quentin. Some of his conclusions are quite generous. For example, he argues that bad sight and hearing may lead some people to become criminals: “The man with poor eyesight surely is less qualified to lead a straightforward life and to properly compete with his fellow beings than the man who is normal in this respect.”

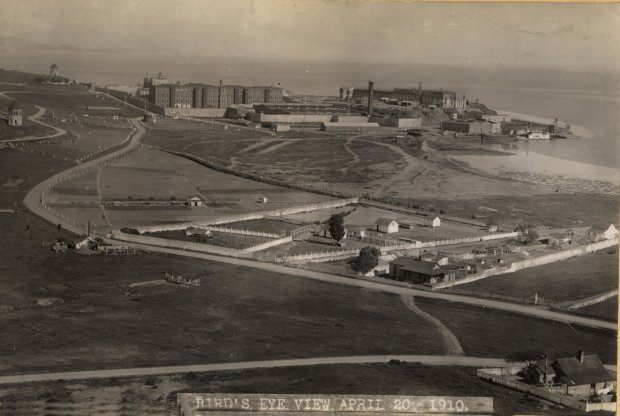

San Quentin Prison in 1910. (Photo: tootsie8664/flickr)

Evidently, however, he found the testicles of inmates suitable enough. One advantage was that many of the criminal at San Quentin were young and, presumably, virile. According to a 1922 Los Angeles Times article, Dr. Stanley implanted goat glands into 1,000 inmates (and a few staff) and 20 full implants of the “still warm” testicles of the executed into elderly inmates. The goat glands were sliced thin, placed into a syringe, and shot into the willing inmate’s abdomen. Dr. Stanley claimed that the foreign matter was “absorbed into the patient’s system without the slightest harm.” The reporter declared from first-hand observation that the experiments worked—the men were less inclined to commit criminal acts. One successful transplant patient, man of 72, who received goat glands became “as lively as a young colt.” The full transplants were described as “remarkable.”

The only negative side effect noted was one case where a man lost his “high tenor” voice and became a low tenor. It ruined the composition of the prison choir.

Residences at San Quentin State Prison for Dr. Leo Stanley, Warden Scott Smith, and Mark Noon, c.1915. (Photo: Courtesy Anne T. Kent California Room/Marin Country Free Library)

The entire field of “rejuvenation” began in Europe in the early 20th century with the promise of a return of youth and virility through surgical means. (One such early experiment implanted chimpanzee testicles into a human.) It was about more than just sex. By increasing sperm counts and improving blood flow to the testicles, doctors thought that men would be able to reclaim their natural masculinity—aggressiveness, competitiveness, improved physical health optimism and hair—as it waned with old age. Dr. Stanley claimed that goat glands cured acne, asthma and diabetes. A New York Times article from the 1920s described the recipient of such testicular enhancement thusly:

“A year ago Mr. Gardner was forced to eat soft foods and wear glasses, but the only physical defect from which he now suffers is poor hearing.” Recipients were routinely described as being able to get up and play golf or talk knowledgeably about intellectual subjects.

But, few men in the U.S. actually received such surgery; people weren’t that willing to undergo the knife for better memory. Hence, Dr. Stanley relied on his stable of confined patients to serve as test subjects. His subjects testimonials focus on their woefully unmasculine upbringings—no “red-blooded exercises,” no firm discipline, and no intellectual stimulation. They all claim to have had bad eyesight, poor physical fitness, and a generally gloomy attitude that were alleviated by the glands.

Dr Stanley with patient Lt. Glenn Brand, 1953. (Photo: Courtesy Anne T. Kent California Room/Marin Country Free Library)

You’d think that the public would react negatively to the whole ordeal and some did: Kelly’s family sued over the mutilation of his corpse. (In addition to his testes, Kelly’s heart and brain were also taken for experiments without their permission.). But, the family lost in the court of public opinion. In fact, Dr. Stanley was routinely praised by the media. In an era where experimenting with sterilization and medical procedures as a way to improve society and reduce crime, his tactics were not viewed as unusual. Rather, they were revolutionary. Publications like the San Francisco Examiner defended Dr. Stanley for innovating the field of curing erectile dysfunction. The L.A. Times exclaimed that Dr. Stanley had “performed more goat-gland operations than anyone else in the world.”

Stanley’s death came just before the prison explosion, when incarcerated populations would increase exponentially. While today, no one advocates the use of testicular injections for erectile dysfunction (there are mechanical apparatuses and Viagra for that), some people do argue in favor of allowing consenting inmates to participate in medical trials and donate organs.

In that way, perhaps, Dr. Stanley was more ahead of his time than he thought.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook