The Dark History of Seven Places Branded by Bloodshed

The names given to streets, corners, and bridges are not only essential to finding our way around, they can also tell a story. However, the story may not always be a pleasant one. How about a leisurely Sunday drive down Shades of Death Road? Or a peaceful afternoon down by the water that earned its name after a day it ran red with blood?

Here are seven places in the United States that might make you ask next time you look at a sign: what really is in a name?

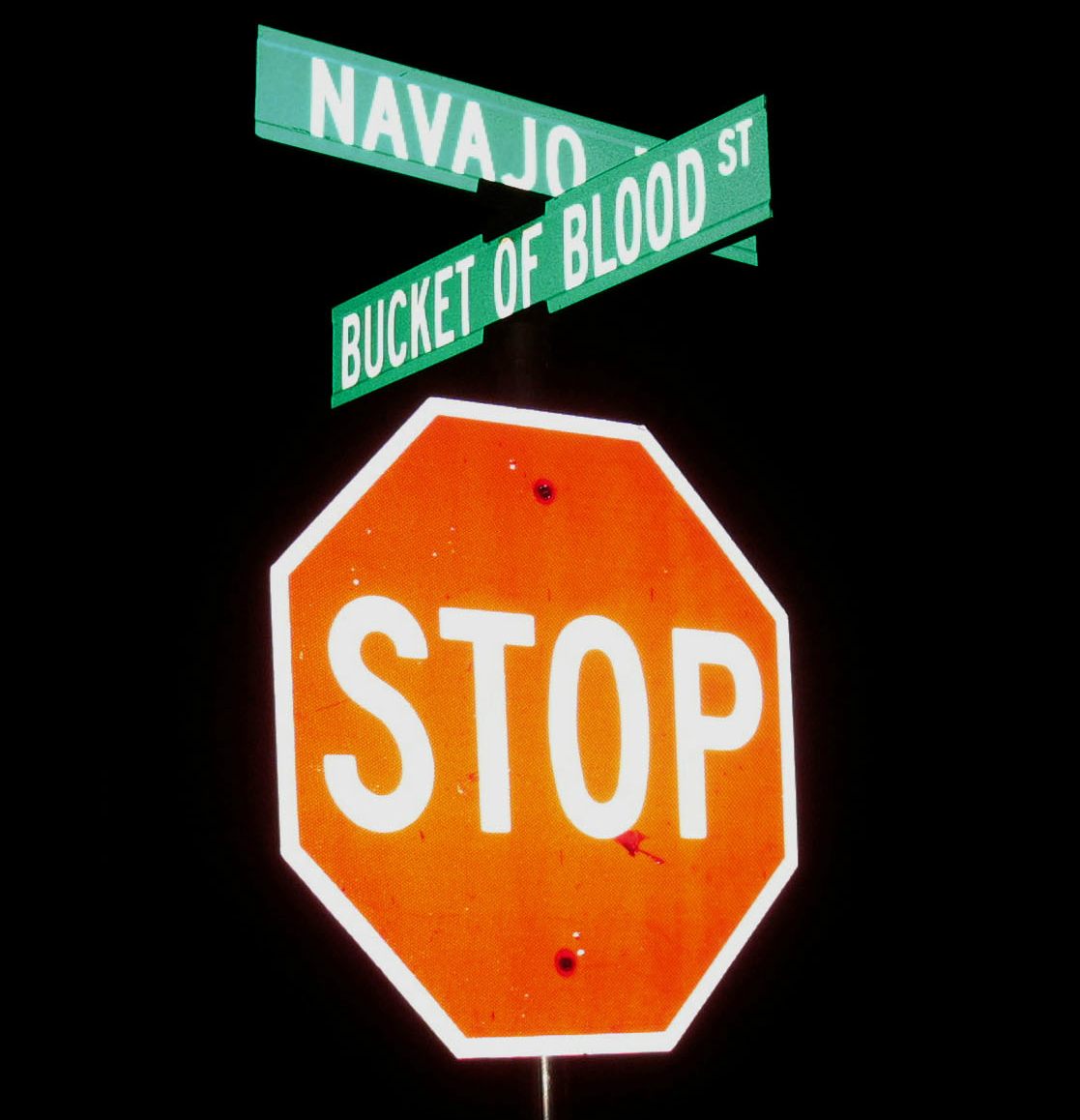

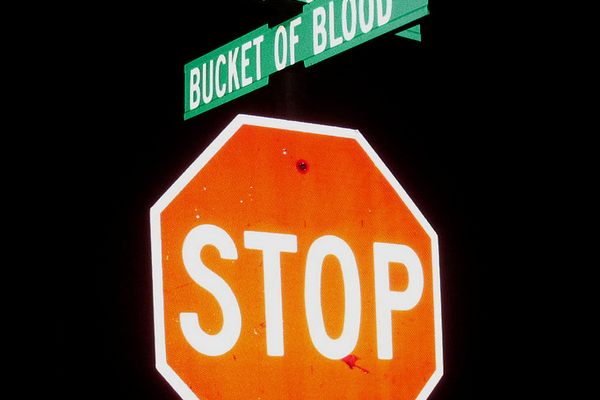

BUCKET OF BLOOD STREET

Holbrook, Arizona

Bucket of Blood Street (photograph by Peter Eimon/Flickr)

Bucket of Blood Street (photograph by Peter Eimon/Flickr)

In a time and place that was known for violence, the Terrill’s Cottage Saloon set itself apart after one evening that left its floors covered in blood and an unknown number of men dead.

In the mid-1880s, Holbrook, Arizona, was a town dubbed ”too tough for women and churches,” due in part to there being no law enforcement to get in the way of rampant gunfights, and the moving in of various rival gangs of ruthless cowboys. Two of these groups of cowpushers — the Hashknife Outfit, known as the “theivinist, fightinist bunch of cowboys in the west,” and the Dalton Gang — are each connected to two of the more prominent stories as to why Terrill’s Cottage Saloon, and the street it sat on, took on its notorious moniker: Bucket of Blood.

In 1886, the Hashknife Outfit were tied to 26 murders in Holbrook, a town of around 250 people. That same year, a brutal gunfight broke out at the saloon between members of the Hashknife Outfit and another group accusing them of stealing cattle. There is no record of how many men were killed, only the description that “buckets of blood” were left in the aftermath. In another version, the notorious Dalton Gang was responsible for all the blood. Allegedly, Dalton Gang member Grat Dalton, a man named George Bell, and two others were engaged in a game of cards and an argument erupted over a hand. Dalton fired his .45 at two unidentified men, leaving them bleeding to death on the floor while he and Bell fled the scene. According to the story, the floor looked like it had a bucket of blood spilled on it. Either way, the name stuck, with the street changing its name from “Central” to “Bucket of Blood” soon after.

The Bucket of Blood Saloon closed in the 1920s, and remains sitting on the street that took its name, heavily surrounded by trees and boarded up, only a few minutes off historic Route 66. A painting that hung inside the Bucket of Blood Saloon is now at the Historic Navajo Country Courthouse: a woodsy scene of trees and water, broken up by two distinct bullet holes.

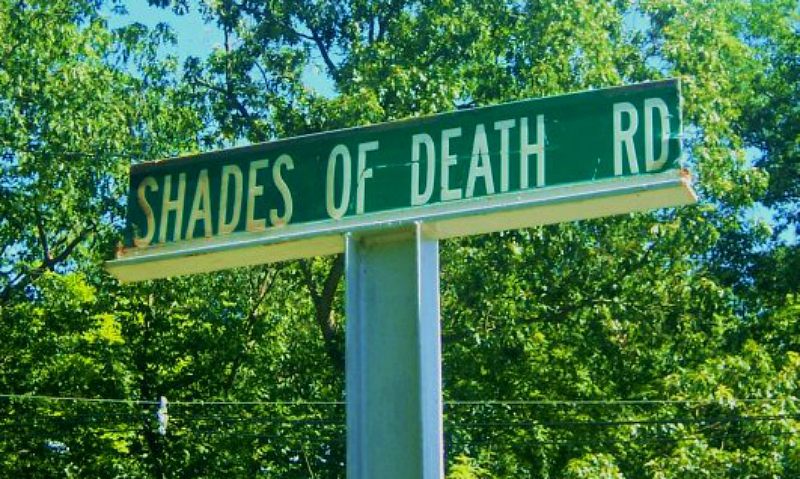

SHADES OF DEATH ROAD

New Jersey

Shades of Death Road (photograph by Daniel Case/Wikimedia)

Shades of Death Road (photograph by Daniel Case/Wikimedia)

On the border of Pennsylvania, New Jersey’s Warren County is no stranger to long and winding rural roads surrounded by trees. Running through the middle of the county is one that shatters the serene surroundings: the seven mile-long Shades of Death Road.

One of the earliest stories of the death-soaked road states it was first referred to as “The Shades.” Around 1850, a malaria outbreak in the surrounding community resulted in the more sinister addition.

Other origin tales are more deeply rooted in cold-blooded murder. Due to the low hanging trees, the road was a base for a band of ruthless squatters who were assumed responsible for a number of murders and disappearances. For all the lore about Shades of Death Road, the name is not by any means unjustified, and there were three confirmed cases of brutal murders connected to it in the 1920s and 1930s. In one incident, a man was bludgeoned to death with a tire iron from his own car and robbed of some gold coins. In another, a man by the name of Bill Cummings was shot to death before his body was dragged out to lay on the side of Shades of Death Road. In the third documented killing a local woman murdered her husband, decapitated him, and buried his head and torso on opposite sides of the road.

JENNY JUMP STATE FOREST

New Jersey

Jenny Jump State Forest (photograph by Famartin/Wikimedia)

Jenny Jump State Forest (photograph by Famartin/Wikimedia)

Because Shades of Death Road isn’t creepy enough on its own, sitting alongside the road in Great Meadows, New Jersey, is the Jenny Jump State Forest, known for its hiking, wildlife, and its unfortunately straightforward name.

According to one story, Jenny was a young girl living in the mountains. She was out with her father when they were spied by several American Indians. As they moved closer, her father yelled out “Jump Jenny Jump!,” and she obeyed, jumping off of a cliff to her death. In another version, Jenny lived with her elderly father in Warren County and was engaged to be married to a local doctor named Frank Landis. Another man, Arthur Moreland, asked Jenny for her hand, but she denied him and told him to never speak to her again. On her wedding day, Jenny was walking along the mountains and suddenly came face-to-face with Moreland, who again asked her to marry him. Frightened, Jenny backed up to the edge of the cliff and threatened to jump. When Moreland said if she jumped she would be killed, she responded: “Death would be preferable to dishonor. If you come one step nearer.”

Jenny kept her word, and when Moreland stepped closer, she jumped from the cliff to the rocks below. Although badly injured, Jenny, in this tale, survived her fall.

DEAD WOMAN’S CROSSING

Weatherford, Oklahoma

Dead Woman’s Crossing (photograph by Nate/Flickr)

Dead Woman’s Crossing (photograph by Nate/Flickr)

Walking along the banks of Deer Creek in Weatherford, Oklahoma, visitors get a tranquil picture of a bridge ominously called Dead Woman’s Crossing.

The name is hard-earned as the place. In the summer of 1905, the body of a young mother was found decapitated. On July 7, a 29-year-old woman named Katy DeWitt James got on a train with her 14-month baby Lulu Belle. The previous day, she’d filed for divorce from her abusive husband and her father, Henry, had seen her and Lulu off at the train station on their way to visit a cousin. Henry normally received frequent letters from his daughter, so when he had not heard from her in several weeks he hired detective Sam Bartell to find out why communication had suddenly gone cold.

After weeks of investigation, Bartell found that rather than get off the train where her cousin lived, James and her baby left the train in Weatherford with a woman named Fannie Norton, known to the townspeople as a notoriously shady prostitute. The women spent the night with Norton’s brother-in-law William Moore, and the next day Norton convinced James to ride with her to a nearby town. Witnesses later recalled that a buggy with the two women and the baby disappeared near Deer Creek for 45 minutes before Norton returned with only the baby, leaving it with a boy on a farm and instructing him to take the child to his mother to care for her. The clothes the baby was wearing were bloodied. Detective Bartell tracked Norton down to the town of Shawnee, Oklahoma, where she was questioned aggressively. Norton vehemently denied any knowledge of the missing mother or the bloody baby. Later that evening, Bartell stepped out and Norton began to vomit violently. She had poisoned herself, and died shortly after.

On August 31, 1905, a local man and his son were fishing along the banks of Deer Creek when they found a skeleton next to a wooden wagon crossing. The skeleton was fully clothed and still wore a gold ring, but the head was separated three feet from the body, and the skull had a bullet hole behind the right ear. A .38 caliber gun was found nearby. James’ abusive ex-husband had a solid alibi at the time of the murder, and it was concluded Norton had robbed and killed Katy DeWitt James before abandoning her baby and fleeing to Shawnee. Mr. James was granted custody of their daughter, and after settling the estate of his wife he moved away into obscurity.

The wooden bridge where the body of Katy DeWitt James was found was torn down 80 years after the murder, but soon after a cement bridge was built nearby which was quickly dubbed Dead Woman’s Crossing.

BLOODY POND

Lake George, New York

Bloody Pond (photograph by Doug Kerr/Flickr)

Bloody Pond (photograph by Doug Kerr/Flickr)

Located on Route 9 south of Lake George Village, New York, is a pond hidden from view and deeply in need of care. Looking at it, one would never know that this was a pivotal point in the French and Indian War that would lead to a British victory. The bloodshed would stain the water, and name of Bloody Pond would stay for the rest of history.

The Battle of Lake George took place on September 8, 1755, and that evening a large group of American Indians and Canadian troops were discovered by Nathaniel Folsom’s company of the New Hampshire Provincial Regiment and the New York Provincials under Captain McGennis. The ensuing battle was brief, but the violence was devastating, with losses numbering between 200 and 300 men. The dead were rolled into the water, coloring it red.

LEG-IN-BOOT SQUARE

Vancouver, Canada

Leg-in-Boot Square (via Vancouver Public Space)

Leg-in-Boot Square (via Vancouver Public Space)

One of Vancouver’s most bizarre stories is in the name of a seemingly innocent shopping plaza: Leg-In-Boot Square.

According to an account by Stuart Cumberland, an entire half of a human leg, still encased in its boot, washed up on the shores of nearby False Creek. The Cumberland account theorizes the leg was all that remained of a man’s encounter with a cougar, but rather than investigate the matter the police decided to display the leg as a sort of gruesome lost-and-found. The limb was stuck on a pike outside of the precinct to wait for its owner.

The owner never arrived to claim the leg, and after two weeks it was taken down and disposed of.

DEAD HORSE BAY

Brooklyn, New York

Dead Horse Bay (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

Dead Horse Bay (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

The beach between Marine Park and Jamaica Bay in New York City is a strange place. The garbage strewn across the beach is not at all modern, with some pieces being nearly a century old. The old bottles, shoes, pieces of metal from yesteryear, and even horse bones all contribute to the grimly-titled Dead Horse Bay.

The bay earned the name in the 1850s when it was surrounded by, among other facilities, two dozen horse-rendering plants. Up until the first decades of the 20th century, horse and other animal carcasses were used to make glue and fertilizer here, and after the bones were used the remnants were often dumped onto the beach, permeating the air with a putrid smell, adding to the manufacturing wasteland. The industry of rendering animal carcasses moved on, but the name remained, even when it later became the site of a landfill. The dump was capped in the 1930s, and then burst in the 1950s, causing an ongoing stream of trash to wash up onto the beach to this day.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook