The D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths Is Famous. But What About Their Forgotten American Stories?

The husband-wife team chose to tell American myths first.

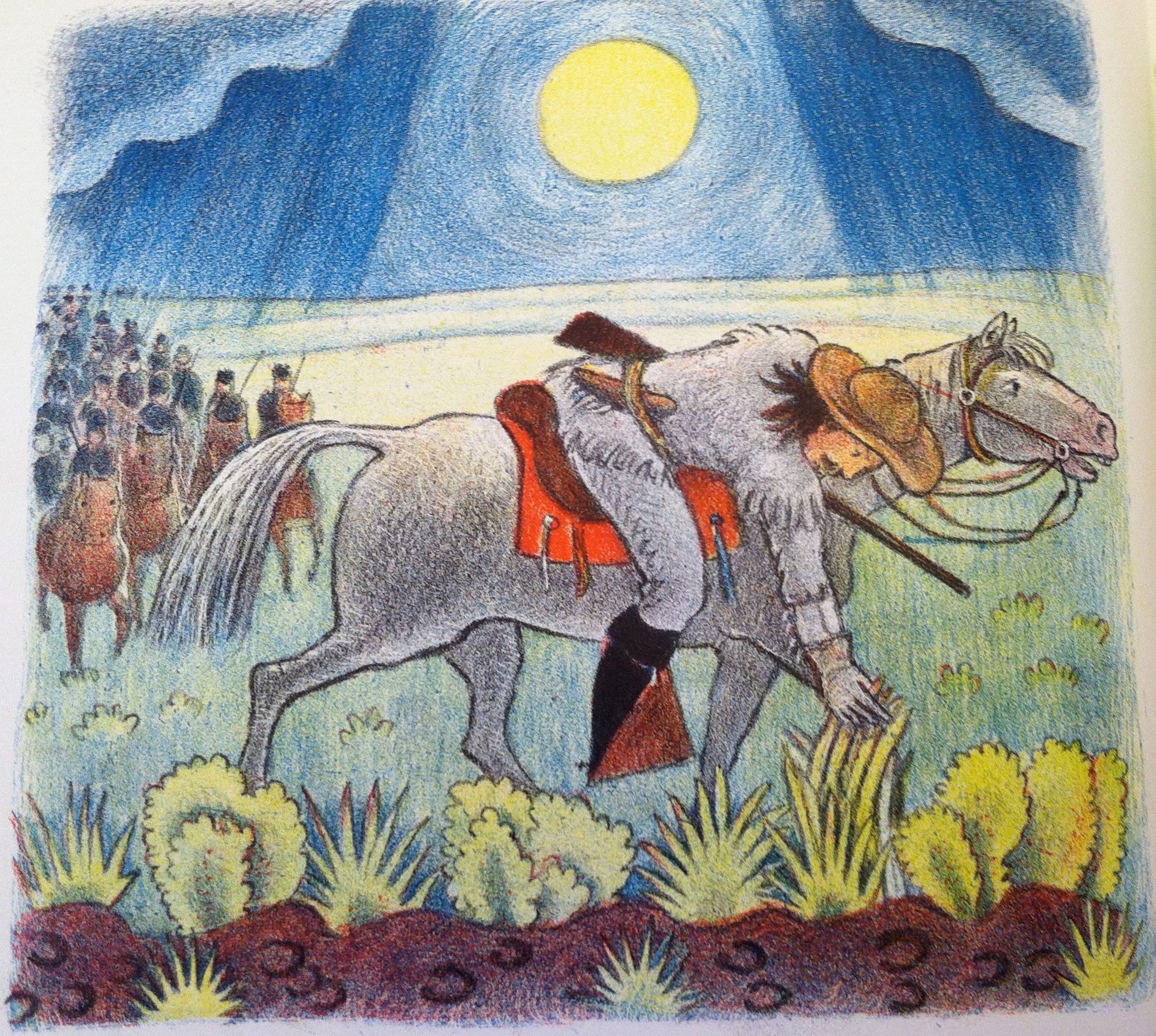

An illustration of Buffalo Bill. (All images by the D’Aulaires, and courtesy of Rea Berg and Beautiful Feet Books. Original D’Aulaire art, sketches, and lithograph stones are held by the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University.)

My favorite book, at one moment in my childhood, was the D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, a big book, with a cover in the bright colors of the sun and lush illustrations inside. Uranus left stars in Gaea’s eyes as they fell in love, Iris ran down a rainbow, trailing her “gown of iridescent drops,” and the gods of Olympus sat arrayed on their thrones, Artemis with her bow, Demeter with Persephone on her lap, Zeus with lightning bolts in hand.

Like so many kids, I thought they were magic.

First published in 1962, the Book of Greek Myths is one of the most popular children’s books ever—it’s still a best-seller. It is the most famous of the books by the D’Aulaires, a husband and wife team of European artists who immigrated to America in the 1920s. But it’s also one of their last.

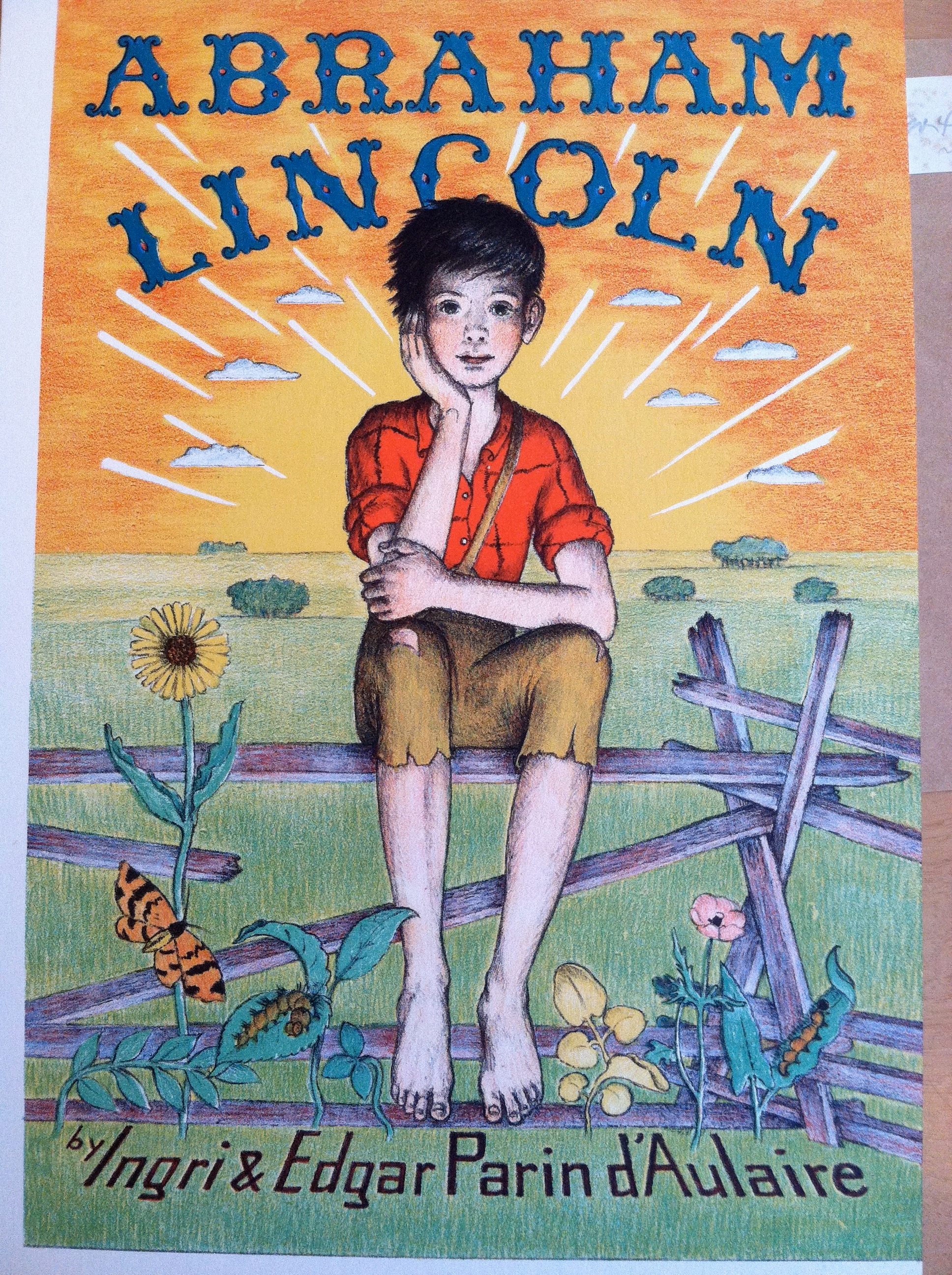

Earlier in their career as creators of children’s books, the D’Aulaires wrote about a different set of myths—of the American variety. Most of their first books were set in Scandinavia, where Ingri D’Aulaire grew up, but soon they moved their focus across the Atlantic, to their new home. In 1936, they wrote a biography of George Washington and in 1939 one of Abraham Lincoln, for which they won the Caldecott Medal. They would write about Pocahontas, Benjamin Franklin, Buffalo Bill, and Christopher Columbus, all before they wrote anything about Greek myths.

These books of American myths, though, have largely been forgotten—even the Caldecott-winning Lincoln biography. I wondered: Why had they fallen out of circulation? Did they have any of the magic of the D’Aulaires’ greek myths?

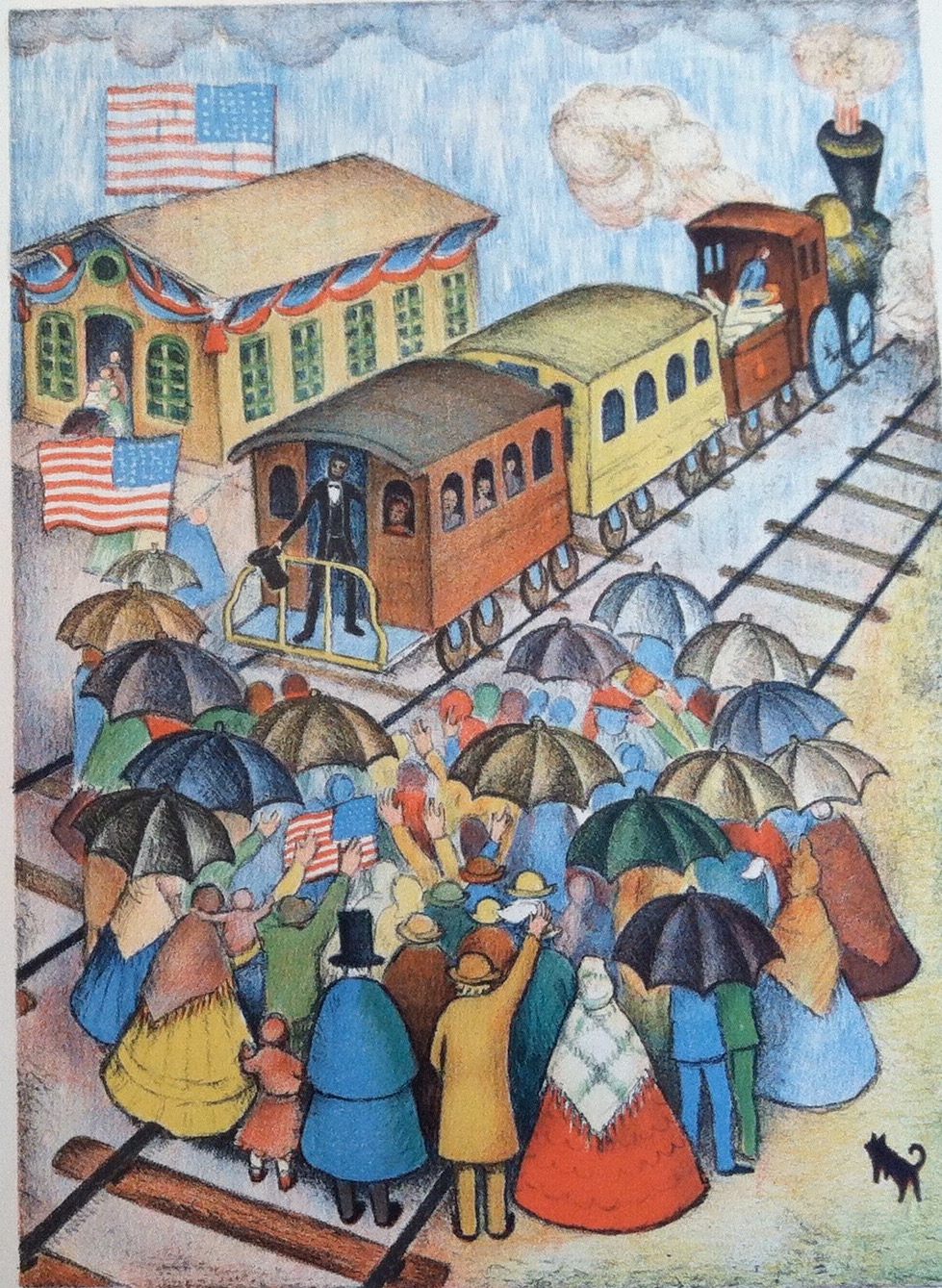

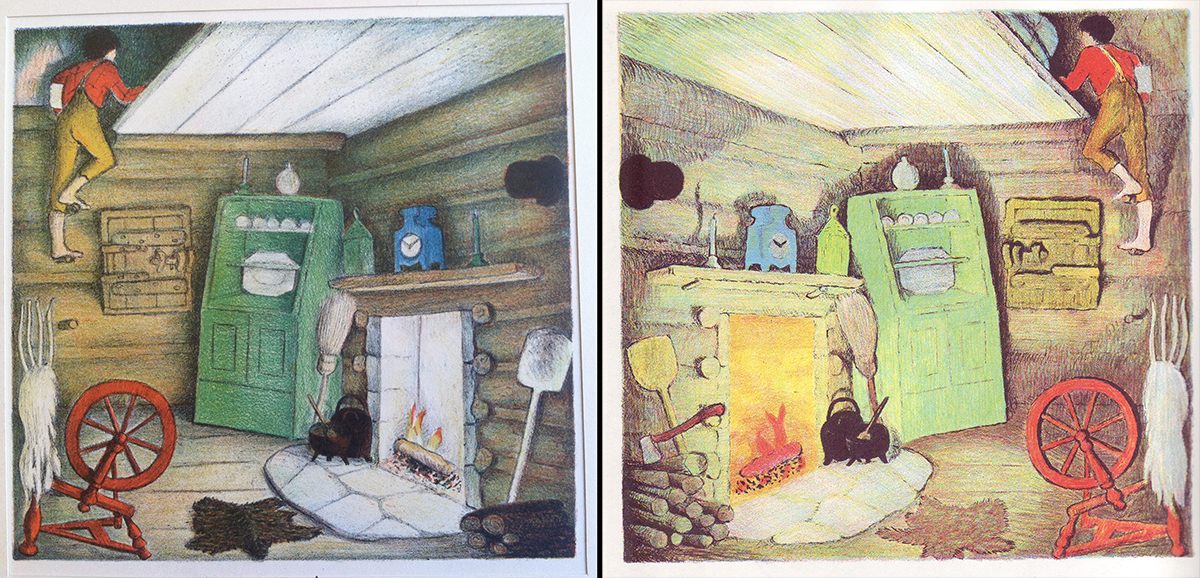

A scene from Abraham Lincoln, showing the influence of Matisse.

The story of Ingri and Edgar Parin D’Aulaire has its own mythic quality to it. Ingri was born in Norway, and Edgar in Germany, where Ingri came to study art. They were married in her country, moved to Paris and started dreaming of America. When Edgar was in a trolley accident, he used the insurance money to sail across the Atlantic, alone, to start a new life. After Ingri joined him, they met a librarian at the New York Public Library who planted the idea of their future: they should use their artistic talents to make books for children.

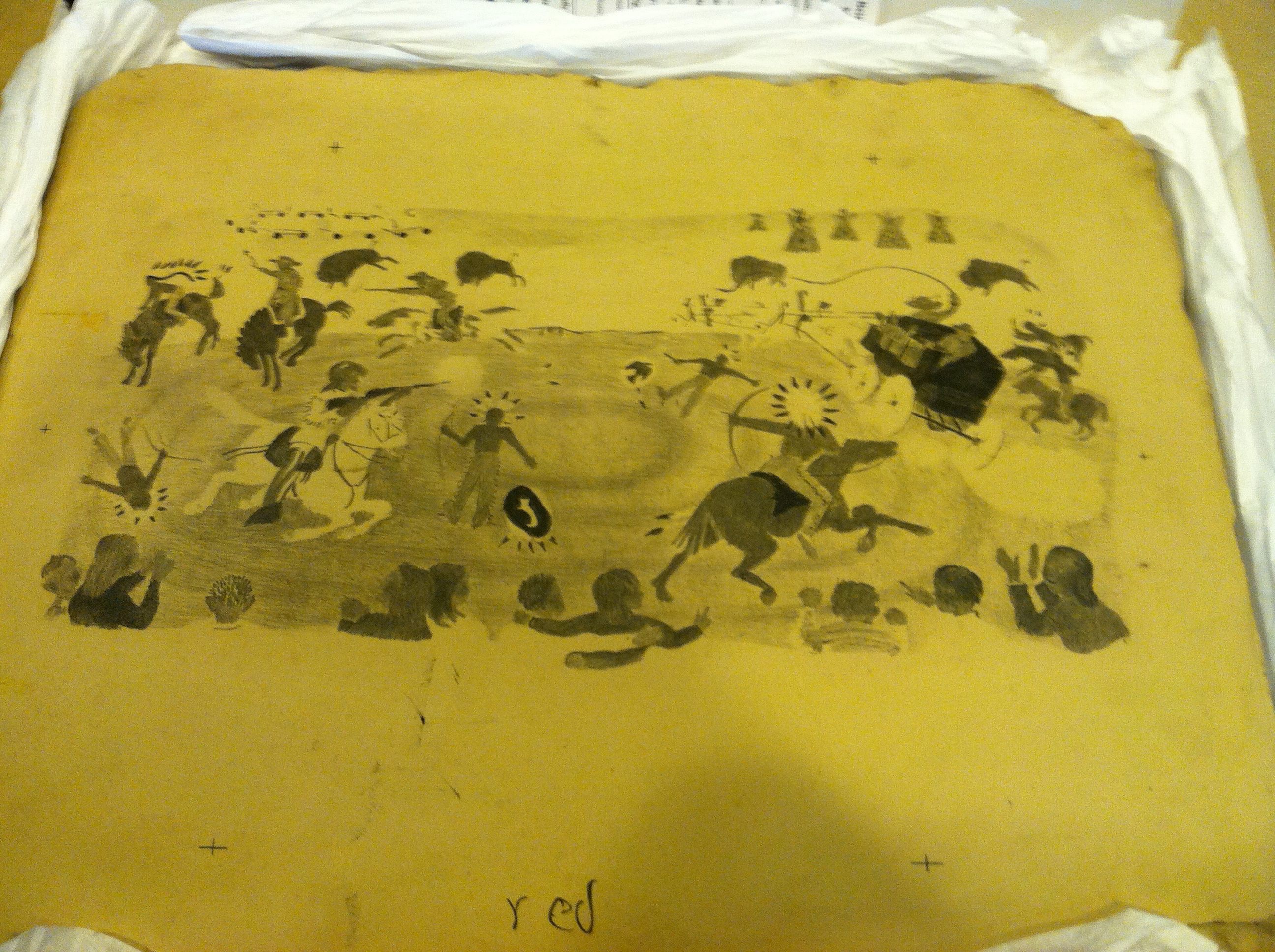

The stone lithography they used for their illustration was a heavy lift. Each page was printed from multiple stones, which could weigh anywhere from 50 to 200 pounds each. The images on each would layer over one another to create the final, rich image. Edgar Parin had studied under Matisse, and their work was influenced by Impressionism. Look closely at the illustrations, and they’re made of tiny strokes of carefully juxtaposed color.

Each illustration was made from multiple stones like this one.

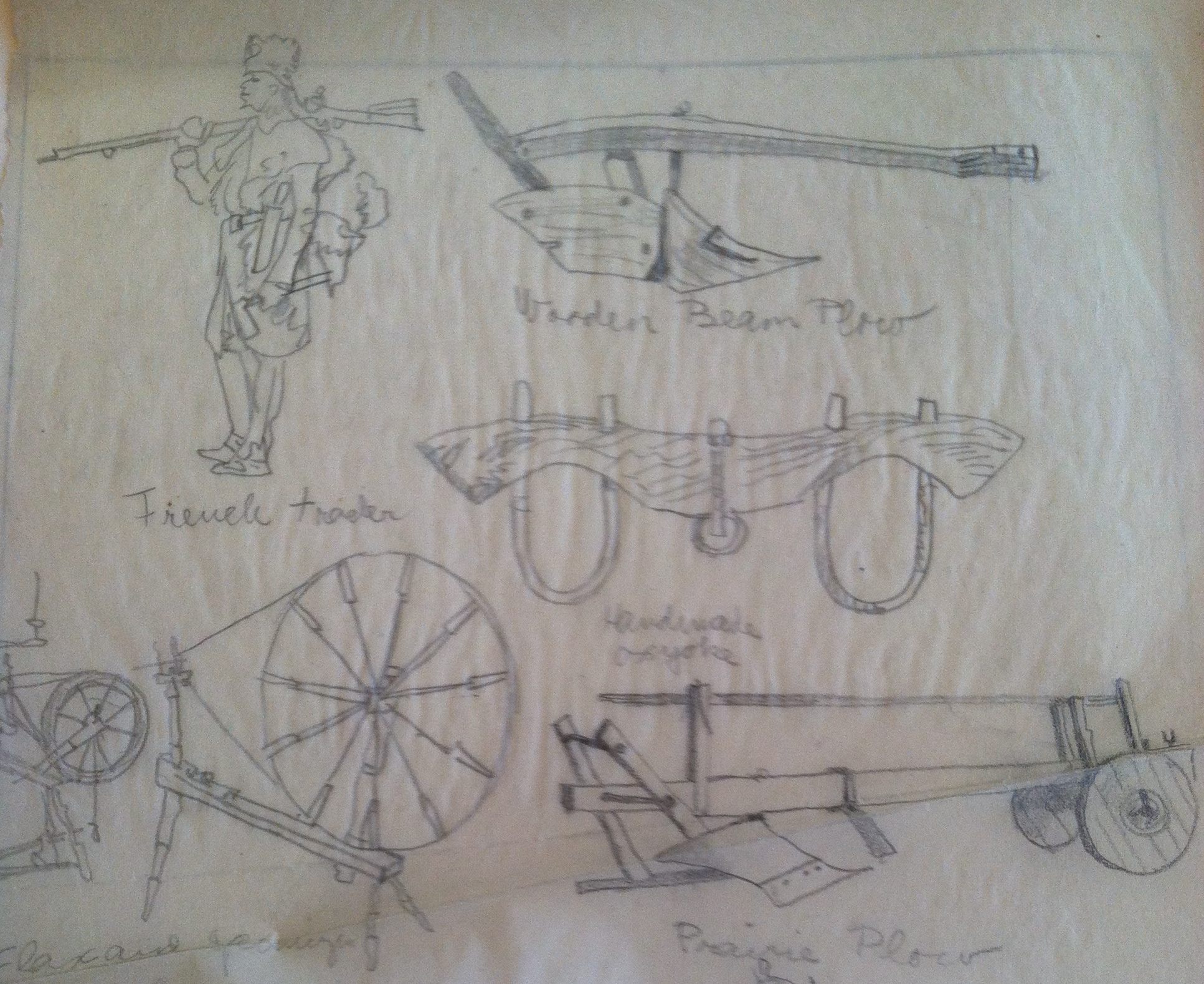

Their research process was possibly even more arduous. They would spend hundreds of hours reading, traveling and sketching before they even started writing or creating their illustrations. When they wrote about Christopher Columbus, they traveled through Italy, Spain and Portugal to see the places he had lived and toured the Caribbean islands he landed on when he crossed the ocean. While researching Lincoln, they sketched dozens of the faces they found in old photographs at the Springfield library and used them to fill in the crowds of people in their drawings.

This attention to detail, combined with their sense of scope, is as important to their books as their illustrations.

The D’Aulaires sketched extensively before beginning illustrations.

This is how their American myths begin.

“Virginia was once a wilderness,” the D’Aulaires write. “Wild beasts lived there, and swift Indians ran through grass and swamps.” Within two paragraphs, hundreds of years have passed. A man named John Washington arrives from England, builds a farm near a pile of oyster shells (created by the people Europeans forced out), and there “his grandson’s son, George Washington” appears in the world.

Columbus’ story gets treated even more like a fairytale. “There once was a boy/who loved the salty sea,” it begins.

Like any mythological hero, the D’Aulaires’ George Washington has powers beyond those of ordinary men. He’s stronger than other boys and rides his horse more skillfully. He can hurl a rock across the width of the river. He’s shot, but unharmed. Lincoln is also demigod-like, when they tell of how he “wrestled with the strongest and toughest of them all, and threw them to the ground.”

But at the same time, their characters comes across as a real people. There’s no cherry tree story in George Washington; Columbus gets petty and angry. Lincoln continues to sit on the floor to read his books, even after Mary Todd tell him those are wilderness manners, not city manners. As much as the D’Aulaires are telling stories about these almost unreal men, the founding fathers also seem more fully drawn than usual. There are details in these stories that, as many times as I’ve been told the stories of these men, I’d never heard before.

The cover of Abraham Lincoln.

Today, these books are printed by Beautiful Feet Books, a boutique publisher in California. Rea Berg, its founder, discovered the D’Aulaires’ American books when she was planning a homeschooling curriculum, and started printing them when she found there was demand for Leif the Lucky, another D’Aulaire book that had gone out of print.

Big publishers, she says, “are not interested in books that they can only sell a few thousand copies a year of.” But with that first book, “people were just so delighted to see it brought back into print.” Beautiful Feet now publishs all six of the American books and recently released a new edition of Abraham Lincoln.

The new edition came with two challenges. The D’Aulaires created these books in the 1930s and ‘40s, and to some extent, their books reflect the mindset of the time. They celebrate Columbus without acknowledging the problems with his colonial drive. The fields of George Washington’s home have slaves working them, and slave children peek through plantation house windows. A member of the Black Hawk tribe cowers behind Lincoln as the future president defends him; freed slaves bend a knee to him after the war is over. The books don’t glamorize colonialism or slavery, but they don’t confront them, either. In the new edition, Beautiful Feet Books made small changes to correct some of the most patronizing portrayals of non-white people.

With Lincoln, the publishers also needed to restore the original art. In the 1950s, the D’Aulaires’ publisher pushed them to put aside lithography and create cheaper, acetate editions of their books. In those acetate versions, the colors changed. “The D’Aulaires had painted this beautiful forest of trees in the moonlight,” says Berg. “They’re these lovely dusky grayish colors. In the revised editions, the trunks of the trees are purple.” The white stripe of a skunk turns green; a fawn gets a greenish cast as well.

For the new edition, Beautiful Feet Books captured the original colors from older editions held at the Beinecke Rare Books library. You can see the difference:

Original art on the left; art from the 1957 version of Abraham Lincoln on the right.

“They chose stone lithography because it gave children a sense of what true art was,” Berg says.

After reading the American books, I looked again at the D’Aulaires’ Greek myths. All the same elements are there: the scope, the detail, the illustrations. In the American myths, my favorite illustrations are the ones that are the dreamiest, the most unreal—Columbus in a Caribbean rainforest, surrounded by lizards, birds and giant flowers, a boyish Washington sitting before a fireplace whose tiles have shadowy images of whales and bears, Lincoln and his sister holding hands in the forest like two lost fairy tale children. In the Greek myths, all these urges are unbound by history and its problems. Plus, the D’Aulaires had practice.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook