The World’s Northernmost Town Toasts the Sun With Mangosteens

Svalbard bids goodbye to dark season with an exotic “Fruit Party.”

The sun rose in Longyearbyen, Norway—the world’s northernmost town—for the first time on March 8, after more than four months below the horizon. Meanwhile, at Svalbardbutikken, the local supermarket, another long-awaited sight returned: the annual Solfestuka Fruktfest, or “Sun Week Fruit Party.”

When the pink light of the first sunrise filtered through Svalbardbutikken’s glass doors, it fell on the harvests of latitudes far south of Longyearbyen’s 78 degrees. There were mangosteens like polished amethysts, rambutans in their spiked sea-urchin shells, bumpy green guavas caching centers soft as custard, and other fruits more at home in a Southeast Asian street market than a Norwegian grocery store. By the time the sun sank below the mountains a few hours later, the mounds of tropical fruit were leveled, soon to be replaced by the usual Arctic staples of turnips, carrots, and cold-storage apples.

It makes sense to celebrate the sun with tropical fruit because it’s “reminiscent of sun and heat, which can be nice to think about sometimes up here in Svalbard,” said Ida Antonsen, a Svalbardbutikken employee who is in charge of purchasing produce for Sun Week as well as the year’s second Fruktfest to mark the last sunset in October. While Svalbardbutikken has similar offerings to supermarkets elsewhere in Norway (it is owned by an independent cooperative but sells products from the nationwide chain Coop Norge), these dark-season bookends are unique to Longyearbyen. Antonsen and her colleagues estimate they have been taking place for about six years.

“And because there are many nationalities up here … everyone can get something they like,” Antonsen added.

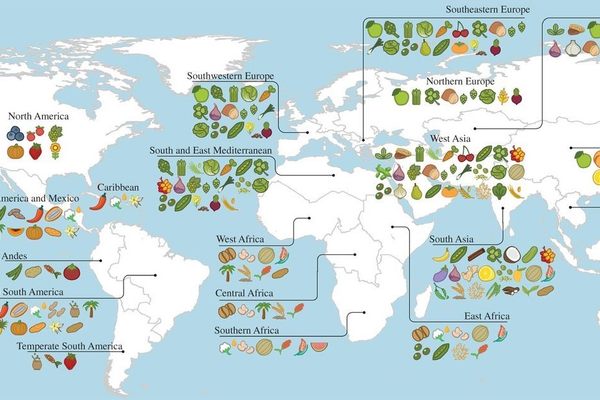

Longyearbyen’s population of about 2,500 includes over 50 nationalities. After Norwegians, Filipinos make up the largest share (115 people as of June 2023); Thais come next (113). There are also large factions from elsewhere in Asia, the Americas, and Eastern and Southern Europe.

This diversity is a downstream result of the Svalbard Treaty, a century-old agreement that recognizes Norwegian sovereignty over this coal-bearing clump of islands in the Arctic Circle—as long as everyone who signed the treaty gets to mine and otherwise commercially exploit the archipelago. Today, Svalbard is a visa-free zone where people of any nationality can live and work legally.

Svalbardbutikken’s workforce reflects that diversity: Its roughly 50 employees come from 13 different countries. About 20 percent are from the Philippines or Thailand, according to Bjørn Ottem, head of grocery, who said they “are very happy to see this kind of fruit arrive all the way up here on Svalbard.”

When I entered the fruit fray, I noticed some Svalbardbutikken employees among my competitors. Staff member Theresa Balisado, from Cagayan de Oro, Philippines, snatched a few bags of bok choy and kiwis from the discount box (containing the produce too bruised or otherwise aesthetically marred to go on the main display) that I had my eye on. I settled on a sack of five mangosteens, which came to almost 100 kroner, or about $9.50.

I presented one to Jonathan Oracion, chef at Mary-Ann’s Polarrigg, after a busy Solfest lunch service—the restaurant and hotel hosted a first-sunrise viewing party in its glass-walled dining room. “Those things are all over the place in the Philippines. We used to whack each other in the head with them,” he told me, lobbing it up and down like a purple tennis ball. He balked when he heard the price. Oracion moved from Manila less than two years ago and remembers paying 50 pesos (about $3) for a whole kilogram.

His friend Winsley Quiambao, the chef and part-owner of sushi restaurant Nuga, joined us in the kitchen and also accepted a fruit. Quiambo, who grew up in Pampanga and has lived in Longyearbyen for a decade, looks forward to the Fruktfest each season and has a weakness for the mangoes. He already had several in his freezer. “I take them out, leave them on the counter a bit, and eat them like that,” he said, with the kind of sheepish half-smile that comes with admitting a private indulgence. “It’s almost like sorbet.”

Along with tropical attractions, the Fruktfest includes everyday fare like oranges, bananas, and grapes, all discounted up to 40 percent. That’s what Kesorn Saenphet, chef and co-owner of Saenphet Thai stocks up on during Sun Week. A native of Thailand who has lived in Longyearbyen for two decades, she has grown used to life without mangosteens and considers them too expensive here.

The price tag makes sense given the long journey the fruit must make to Longyearbyen. Antonsen starts reaching out to suppliers to plan for Solfestuka in January, and the cornucopia requires three deliveries, two by plane and one by ship. In the summer she’ll start planning for October’s last-sunset Fruktfest. “When you think that you are almost at the North Pole, I think it is quite fantastic that we can actually offer fruit parties and exotic fruit to our customers,” she said.

Some question the emissions involved in shipping tropical fruit so far north. But Lukas Schnermann, a climate activist studying methane emissions in Svalbard, believes there are more important things to worry about in the warming Arctic. “The big emissions are the general way of life here and not this event,” he said, noting that importing fresh fruit sometimes uses less energy than storing it at cold temperatures through the winter. “I believe it’s a waste of time and energy to wonder about the carbon budget of twice-a-year imported exotic fruits into an Arctic community that lives off 100 percent fossil fuel energy.”

His friend Aztrid Novillo—a photographer, filmmaker, and fellow environmental activist from Ecuador who moved to Longyearbyen last year—considers the Fruktfest an acceptable indulgence. She encountered mangosteens for the first time at the last-sunset fruit sale in October and bought a few because they reminded her of the caimitos of her childhood.

Called star apples in English, caimitos have hard purple shells and soft purple interiors, chastely sweet, like applesauce. Mangosteens’ shells are similar, but they conceal a secret: a plump, white rose—the edible aril that surrounds the seeds—with the scent of wildflowers and a flavor like peach edged with lightning.

“They were so amazing,” Novillo said, her eyes growing wide at the memory. She thought of them through the long polar night and bought 30 as soon as they returned. “To try out something new like this all the way up here; it’s really special.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook