The Forgotten ‘China Girls’ Hidden at the Beginning of Old Films

Used as quality control, these haunting images were never meant to be public.

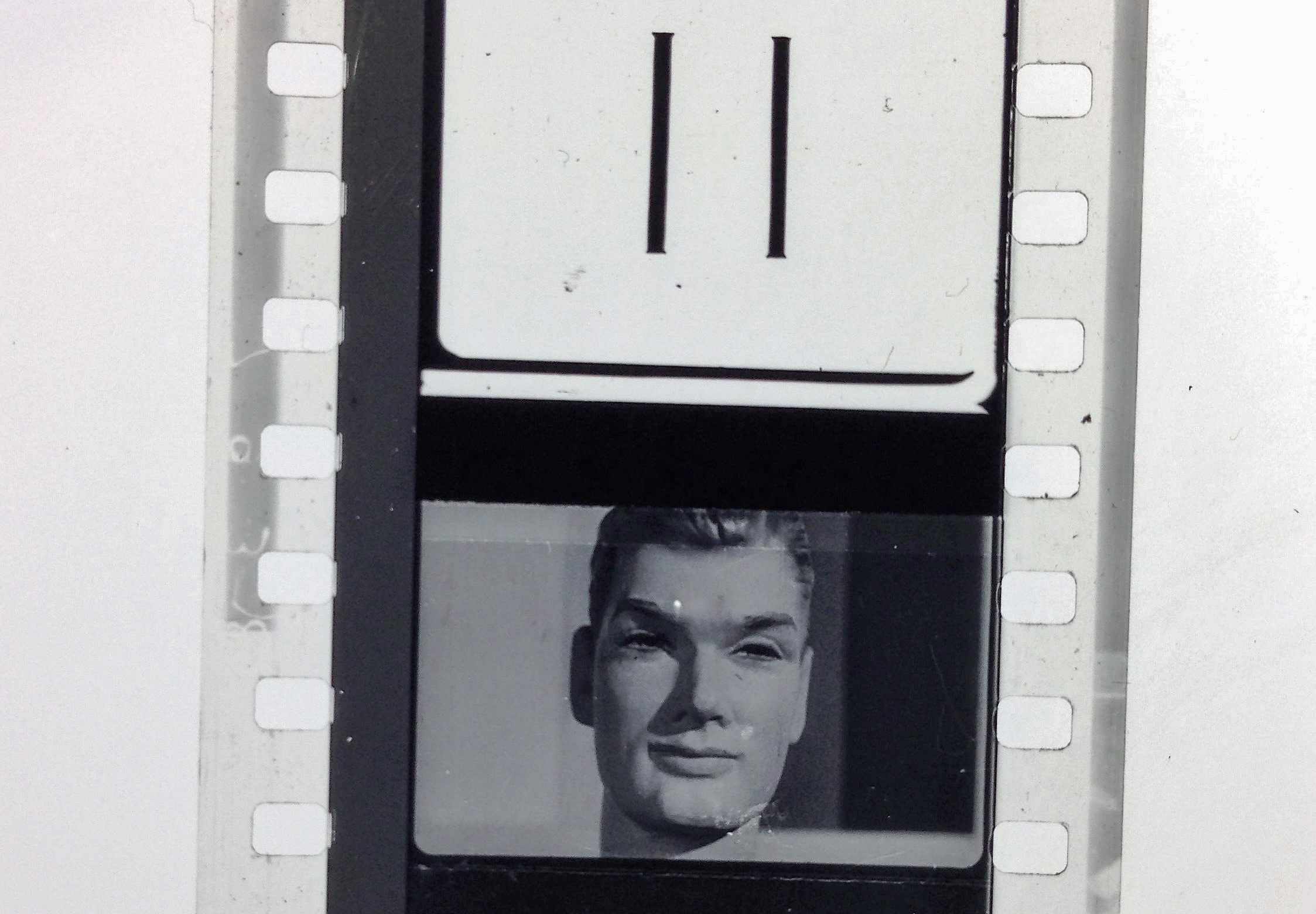

Few people ever saw the images of China girls, although for decades they were ubiquitous in movie theaters. At the beginning of a reel of film, there would be a few frames of a woman’s head. She might be dressed up; she might be scowling at the camera. She might blink or move her head.

But if audiences saw her, it was only because there had been a mistake. These frames weren’t for public consumption. The China girl was there to assist the lab technicians processing the film. Even though the same person’s face might show up in reel after reel of film, her image would remain unknown to everyone except the technicians and projectionists.

For many years photo labs would produce unique China girl images; around a couple hundred women, perhaps more, had their images hidden at the beginning of films. As movies have transitioned from analog to digital, though, the China girls are disappearing.

China girls went by many names—leader ladies, girl head, lady wedge—but they were almost always images of women, and those women were almost always white. They were meant to show the person developing a film that everything had gone right technically; if it hadn’t, the China girl’s skin tone would look unnatural.

Film labs started creating these images back in the black-and-white era. The term “China girl” is thought to date back to that time, although no one has pinned down exactly what it’s supposed to mean. (One popular explanation links it to the porcelain-like quality of the women’s skin; another cites the flower-print shirts early China girls wore.) There’s little information, too, about who these women were. Probably some were models or would-be actress; others were women who were dating people who worked in film labs or worked in film labs themselves.

“A lot of them are made up and done up, but some of them look they just pulled some ladies out of the hallway,” says Rebecca Lyon, a film projectionist who runs the Leader Lady Project at the Chicago Film Society. “There are certain women who look grumpy or vaguely unhappy to be there, and I enjoy those. It reminds you that they’re not meant for public consumption.”

Back in 2011, the Chicago Film Society started collecting pictures of China girls and posting them online. Most of them were found by film archivists or working film projectionists. Once, projectionists might have snipped the images off the end of the film—they’d already served their purpose—and post them around the booth or keep them for a private collection. These days, it’s possible to capture them with a phone camera.

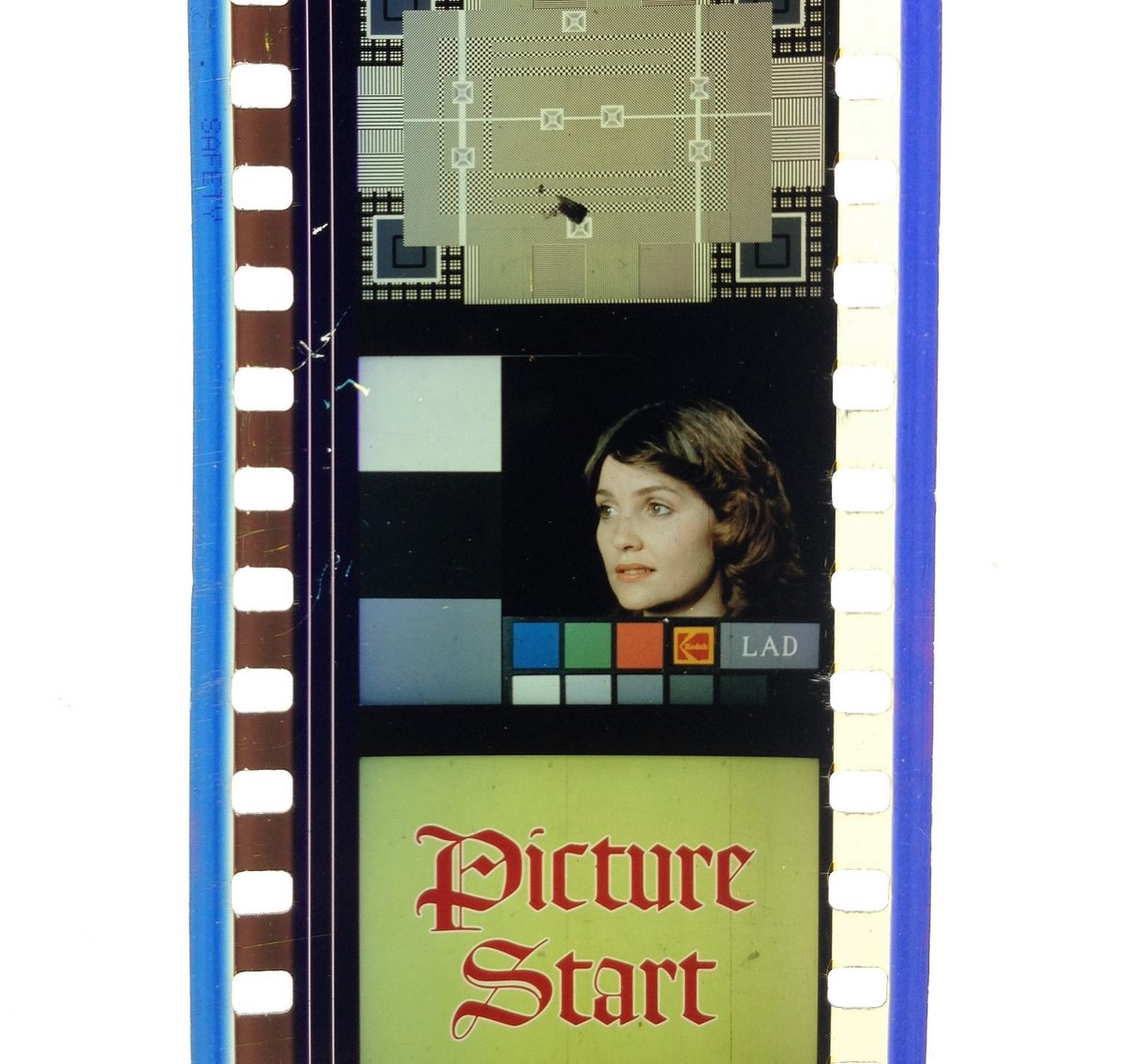

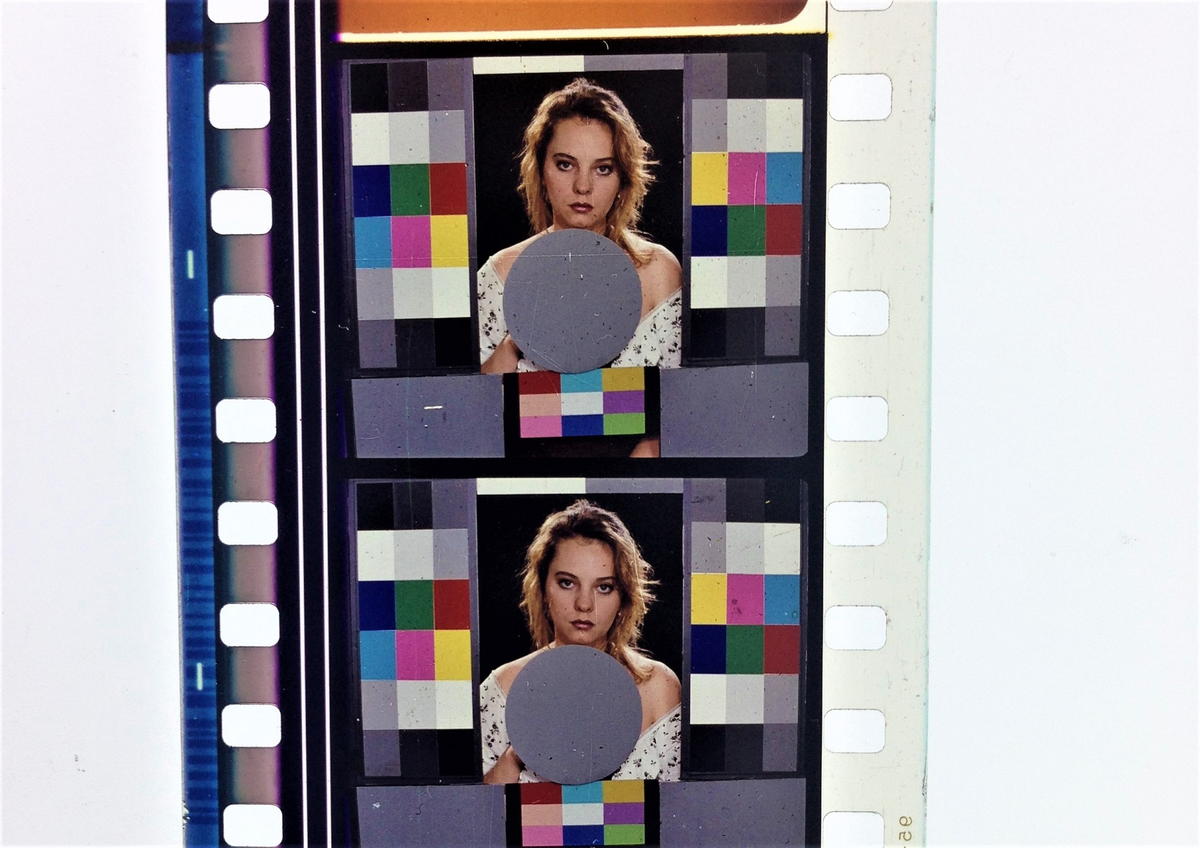

Most of the photos follow unspoken rules. They show the woman from the shoulders up; sometimes her shoulders are naked. They almost always included blocks of grey or different colors, another tool for calibrating the color of the film. Usually they’re looking off to the side. The Leader Lady Project has collected and posted around 200 China girl images, including some unusual specimens showing men, mannequins, and people of color.

There’s little formal documentation of this practice, though. When Genevieve Yue, an assistant professor of culture and media at The New School, started researching China girls, she found that she had to search for terms adjacent to these images—“densitometry,” a part of the quality control process, for instance—to find any information at all. Few film scholars had heard of the China girl; she went to interview lab technicians to better understand these images.

“It is strange, going into labs, where there are China girls everywhere,” she says. Labs need many, many copies of these images, as they continually calibrate their equipment, so their spaces fills up with the same woman’s face. Sometimes they used the same images for years; in one lab Yue visited around 2010, the image they were using had been shot in the ‘90s. (The woman featured in the image still worked at the lab.) “They’re such a naturalized part of the lab culture,” says Yue. “It’s totally vernacular—one person will teach another.”

Starting in the 1980s, though, it became less common for labs to create their own China girl footage. In 1982, Kodak’s John P. Pytlak developed a standardized image, known as the “LAD girl” or “LAD lady.” (LAD stands for Laboratory Aim Density.) He later won an Oscar for his work. By the 1990s, it was finally dawning on film creators and processors, too, that using a white-skinned person as the universal standard was short-changing people of every other skin tone.

Today, there are still images that might be unfamiliar to the public but are famous among technicians who work on creating images for mass consumptions. Kodak has a digital LAD images, and image software also often includes calibration images. But few labs create their own.

One exception is Colorlab, in Rockville, Maryland, which has been in business since 1972 and is one of the last full-service film labs operating in the country. For years, they relied primarily on Kodak’s standardized LAD girl. But there’s no standardized LAD girl for the newest version of Kodak film, and the lab has revived the practice of making in-house China girl images. The most important part, technically, is the grey patch, where the film’s density can be measured; the person’s face is a more subjective measure of quality. Does it look right? Are the shadow details right?

“In the lab, you’re sitting there staring at the image so critically,” says the lab’s Thomas Aschenbach. “To know that your face is going to be up there and everyone’s going to be looking at it … It’s hard to get people in front of the camera.”

In labs where the China girl was used for years, Yue, the New School professor, found that there’s a nostalgia for the practice that surprised her. “One very old lab person got kind of misty-eyed,” she says. He said she was glad she was researching the topic. “Because it’s a face, it’s more than an instrument. If you’re a lab technician, you’re looking at the same face for every day.”

“When I went into the research, I was ready to be kind of dismissive of the lab culture that produced this image,” she says. “But talking to people—it’s much more complex than a bunch of men leering at women. It was woven into the life of a film laboratory. Because I have been researching this right before and during the closing of many film labs, there’s this sadness and feeling of imminent loss in all of my encounters.”

For Lyon, collecting images for the Leader Lady Project means documenting that world, in one particular way. “So much work goes into this process that people don’t really think about,” she says. “The women were representative of this unseen world, and the collecting of these images has been a way to push back against the tide, the black hole where all this analog stuff is going into.” By collecting the China girl images, she’s both revealing these long-hidden practices and keeping them from disappearing entirely.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook