The Ghost Forests of Christmas Past: How A Fungus Stole Roasted Chestnuts

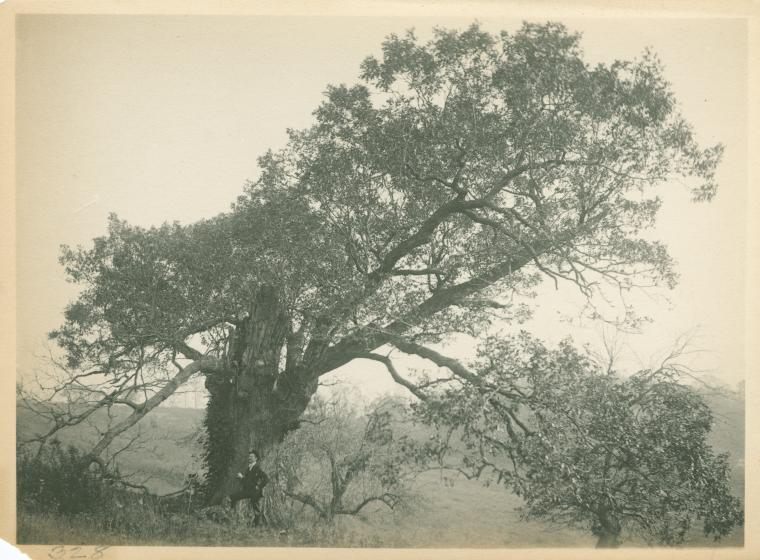

Chestnuts were gigantic trees (Photo: NYPL Collections)

Imagine this: a train car filled full to the brim with chestnuts, small and sweet. Bags and bags and bags of chestnuts pulling into the rail yards of New York City. Chestnuts roasting on streets corners in Baltimore and Philadelphia. Chestnuts inches deep on the forest floor of the Blue Ridge Mountains, from trees so giant they might be more than 100 feet tall and wider than a person is tall.

This is part of what the turning of fall into winter used to mean–chestnut season, when city people would go nutting in the great parks, and mountain people would race pigs and wild turkeys to gathered the prickly burrs from the ground, pounds and pounds of them, to bag, sell, and send north.

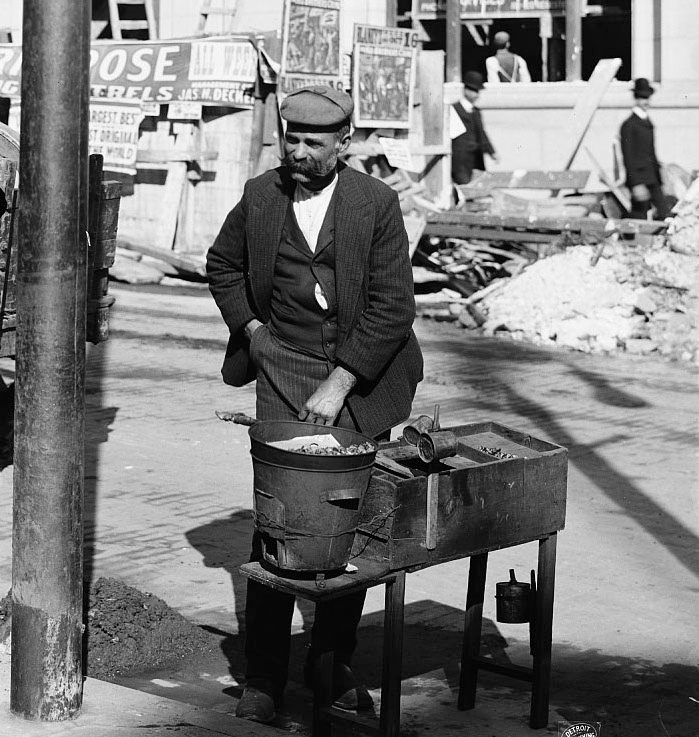

But, today, when seasonal produce is all the rage, only a select few farmers markets peddle chestnuts, and at the supermarket, there might be a sad basket of golf ball-like nuts, nothing like the acorn-sized chestnuts of old. Street vendors sells honey-roasted peanuts, cashews, almonds and pecans, but chestnuts are nowhere to be found.

What happened?

A chestnut vendor in Baltimore, Md. (Photo: Library of Congress/Detroit Publishing Co)

For centuries, different varieties of chestnut trees were cultivated around the world. Their nuts could be boiled, roasted, cooked into porridge, ground into flour and used for months to sustain a family. Centuries before they were being hawked on the streets of New York City, chestnuts were being sold by street vendors in Rome.

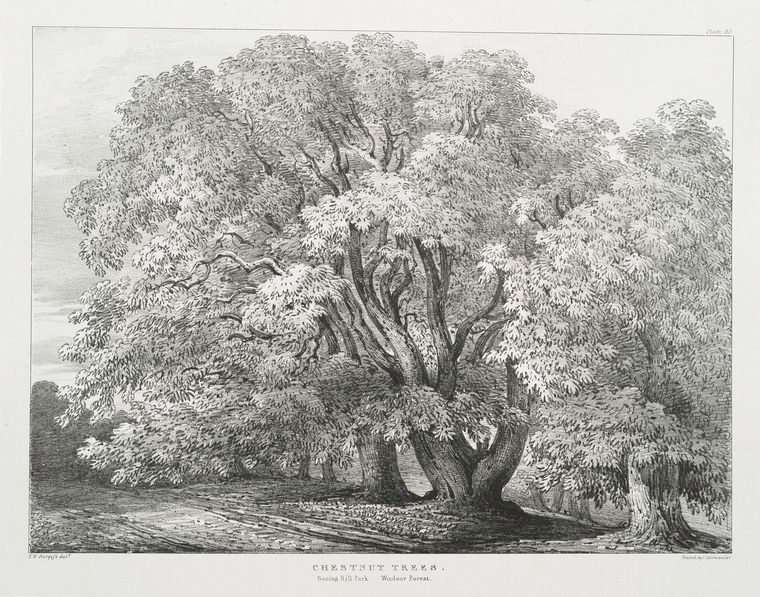

But the American chestnut was not so thoroughly cultivated; it ran wild, up in the mountains, all the way north in Maine and down south to Georgia and Alabama, west to Ohio and Kentucky. In some places, half of all the trees in the forest were chestnuts trees, and they were beautiful. In the spring, their branches were covered in a fluff of white flowers, and the trees grew so large, they gave people that frisson of awe. There’s even a story, says Ralph H. Lutts, an environmental historian who’s written about the chestnut trade, of a chestnut tree so large that when it was cut down, it couldn’t be moved by oxen. The loggers had to dynamite it into pieces to pull it away from the placed it had been felled.

A flowering chestnut (Photo: NYPL Collections)

A flowering chestnut (Photo: NYPL Collections)

In Virginia and North Carolina, in the Appalachian range, families living in the mountains had long depended on chestnuts for food. But in the late 1800s, with railroads reaching remote mountains places, chestnut season became a boom time for mountain communities, particularly places where poverty was most stark. People would spend their days gathering pounds upon pounds of nuts, and pulling them to the rail station by the wagonload; poor families could pay off their debts entirely in chestnuts. Train cars full of chestnuts would pull out of small towns and deliver their loads to large coastal cities, which would feast on the seasonal delight. One year, Patrick County, Virginia, which Lutts write about in his article “Like Manna From God: the American Chestnut Trade in Southwestern Virginia,” shipped 160,000 pounds of nuts out.

That’s a huge amount of nuts, and probably underrepresents the true scale of the trade. “When you think that that’s what they reported to the federal agricultural census and these were mountain folks who were very suspicious of the government, that must have been the tip of the iceberg,” Lutts says.

The end of this era began in 1904, when a gardener in the Bronx noticed that a chestnut tree in the New York Zoological Park had come down with a mysterious ailment. Soon, reports were coming in trees dying all across the city, then in Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. By the 1920s, the chestnut blight had reached the Piedmont region of Virginia and North Carolina.

Chestnut season was over, and it affected not just the people living there. The bears, turkeys and pigeons that had depended on the chestnuts began to dwindle. Farmers no longer let their pigs wander the woods to fatten on the chestnuts that fell to the forest floor. And some people who did depend on the chestnut trade left to look for paid work, just around the time the Depression set in.

A ghost forest of chestnut trees in Virginia (Photo: Library of Congress)

The blight was traced to an Asian variety of chestnuts that had been imported to the U.S. Unlike the American chestnut tree, the varieties that grew elsewhere in the world had been bred to grow larger, more watery nuts, and it’s these, reportedly much less tantalizingly sweet than the smaller American chestnuts, that are sold in stores today. There are few American chestnuts that escaped the blight, and scientists have worked to breed American chestnuts, using both conventional and genetic modification techniques, that are blight-resistant but produce those sweet, native fruit.

The American chestnut had small, sweet nuts, the size of acorns (Photo: Wikimedia)

The old American chestnuts still haunt the mountains, though. The blight did not kill the root systems of chestnuts, so even though the big old stems of the trees have died, even now the root system will produce new growth. These saplings can even grow tall enough to start feeling like trees. Eventually, though, the blight gets them, too.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook