The ‘Great British Bake Off’ of the 1600s Would Have Been All Alphabet Cookies

Bakers flaunted their talent by creating letter-shaped pastries.

Today, a baker might show off their skills with cronuts, which take three days to prepare correctly, or a towering cake modeled after a famous piece of architecture. But in the early 1600s, when literacy was still low, women displayed their domestic and scholarly prowess by baking perfect pastry letters. This craft was once the height of fashion, but today it’s all but disappeared, except in the Netherlands, around Christmas time, and in Iowa.

Edible letters, Wendy Wall argues in Recipes for Thought Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen, were a part of a 17th-century “kitchen literacy” that created opportunities for women to practice and perfect reading and writing. This craft extended from decorative swirls, similar to what might adorn cursive handwriting, to actual pastries formed in the shape of letters.

One desirable skill for women of the era was creating decorative “knots” of interlocking lines, either on the page or in food. In a simple form, these knots might be made from two strands of dough, twisted together and formed into a loop, before being baked. These sort of flourishes resembled the twists and turns that cursive letters might take—as Wall reports, writing manuals at the time considered knot-making a key tool for developing cursive writing skills.

When they were shaping delicate pastry and cookie dough into swirls, braids, and knotted loops, women were actually practicing the same art they’d use to write their letters.

Pastry letters were not quite as ornate as cursive handwriting, but they required more deftness to master. The instructions of recipes at the time were so vague that women would have to know exactly what they were doing: one recipe for “cinnamon letters” instructs the baker to roll the dough into long rolls and then “make fair capital Roman letters, according to some exact pattern.” These letters were a step above cookies or pastries in simple knots—they were “the hallmark of elegant dining and a source of intellectual contemplation,” Wall writes.

Hundreds of years later, the recipes don’t give many hints at how pastry letters might have been presented. Was it more impressive to bake the whole alphabet or to focus on the hardest-to-form letters? (B seems like it would be a challenge.) Would pastry letters spell out words, even sentences? Or was it enough to just pick a few?

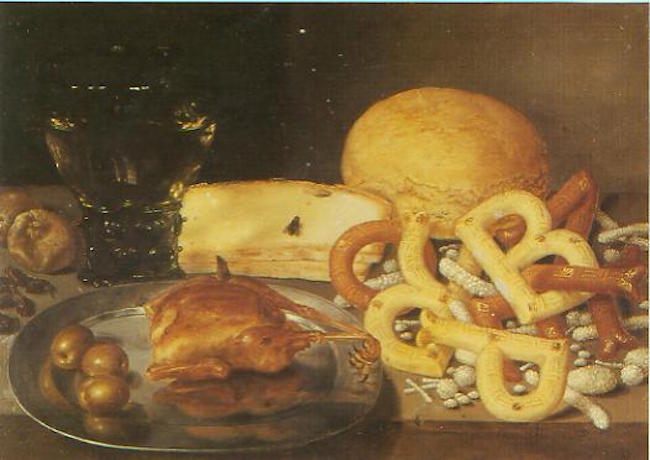

One possibility, Wall suggests, is that pastry letters made puzzles. In one of the only clear pictures of this art, a still life by Peter Binoit, there’s a pile of letters—a P, a B, a T, and an R—all letters from the artist’s name, she notes. Perhaps the letter pile was meant to be an anagram of sorts.

It’s a charming theory. Indeed, the letters resemble the sort of puzzles Graeme Base would have used in The Eleventh Hour, and word games were popular at the time. And, to the extent that letter pastries are still made, they are associated with names.The social cachet of making pastry letters diminished with the increase of literacy, and the art has all but disappeared. Today, they’re more of a cute trick for kids, easily shaped by cheap cutters or molds.

But the 17th century practice does survive in a few places—most prominently in the Netherlands and in Iowa, where they show up around Christmas time. In the Netherlands, Christmas pastries include letterbanket, formed into the first initials of children’s names. Good kids might get this treat as a sign that Sinterklaas favors them.

In Pella, Iowa, a town founded by Dutch Separatists in the 19th century, the same tradition has been carried on for more than a century. The bakeries there have narrowed the tradition down to one letter, though: They make S for Sinterklaas.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook