The Hidden Civil War-Era History Behind a Victorian-Style Cottage in Texas

The Slover-Rogers Cottage in Alvin, Texas reveals the long personal history of a Civil War veteran.

In the early 1900s, Civil War veteran John G. Slover spent the better part of a decade building himself the home he had long dreamed of—and nearly lost. In Alvin, Texas, he constructed a petite-if-impressive Victorian-style gingerbread cottage, using only a jigsaw and hand tools. The sage green cottage (not the original color, it should be noted) boasts gingerbread molding, painted in varying shades of pale yellow and maroon. Comprehensive trim work, columns, and built-in window boxes add to the fantastical nature of the home; the pitched, shingled roof, sweeping upward, has an almost Seussian feel.

Now named the Slover-Rogers Cottage, the fairy tale-esque cottage has been preserved through the Alvin Museum Society. The cottage is more than a home; it’s a living piece of art, tracing the history of a man and a town in the aftermath of the Civil War.

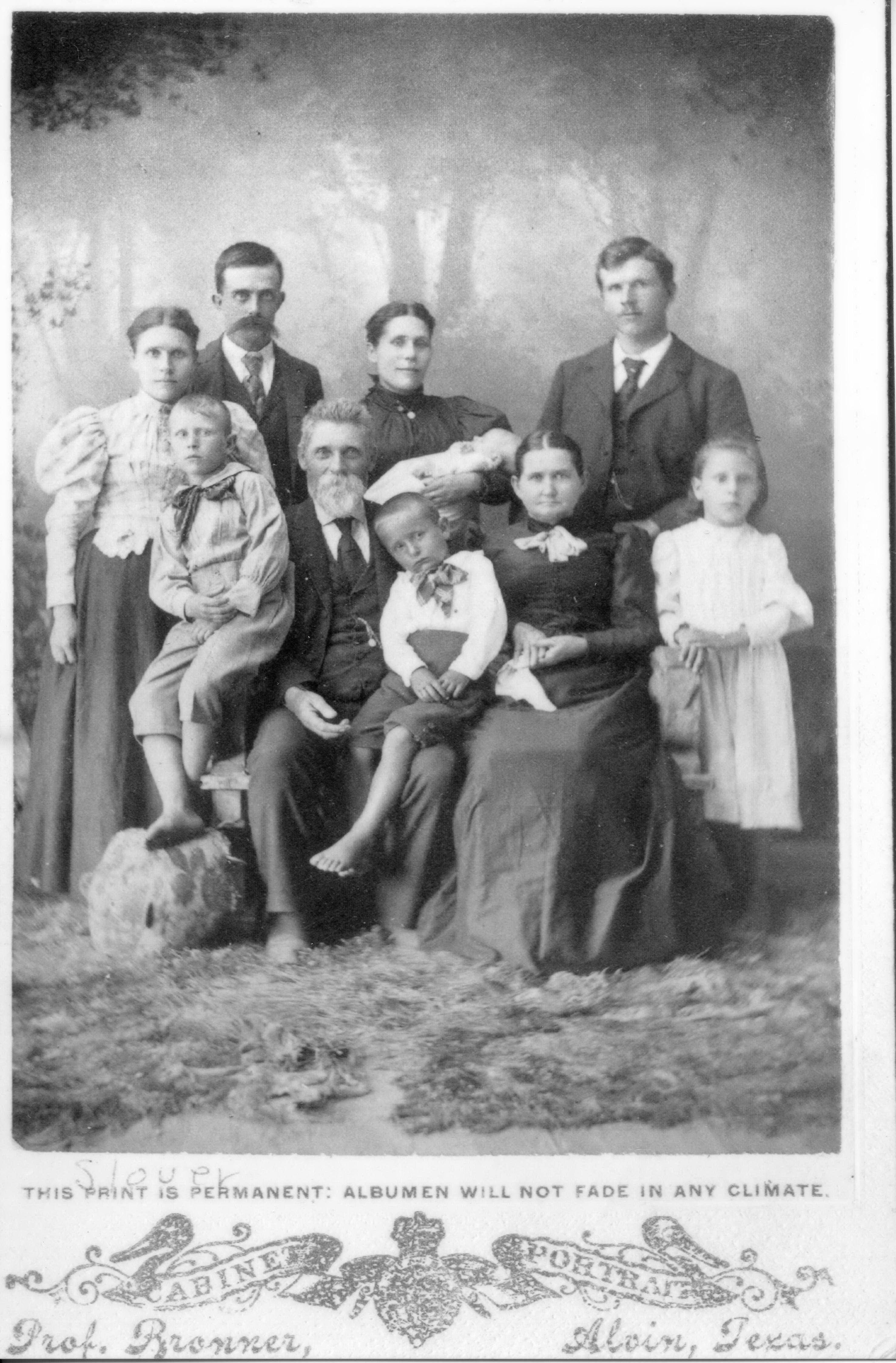

Slover was originally from New York, and had fought on the Union side during the war, primarily along the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas. “After 22 months away, he returned home to his wife and three children in Wisconsin, a veteran of Indian fighting and hunting Rebel guerilla units throughout Kansas and neighboring states,” writes Glenn Starkey in the afterword to Through the Storms: The John G. Slover Diaries.

Slover was not well adapted to such a timid, domestic life. In 1866, less than a year after leaving the military, he left for Kansas with his wife, Mary, and their children. They welcomed a fourth child that same year; eventually, the census would record eight children in total.

“He was looking for property to see if he liked parts of Kansas,” explains Tom Stansel, Chief Operations Officer of the Alvin Museum Society. “He actually found a piece of property that he thought was wonderful, and he ended up there after the war.” That property in Saline County was large enough for Slover to attempt to form a makeshift homestead. But years of persistent crop failure created financial problems. Slover sold the property and moved on to Independence, Kansas, saving money in preparation for another move.

In 1884, after 18 years in Kansas, Slover, now 50, relocated his family to Indianola, Texas, where he fell into work as a carpenter. “He was there, building this house for somebody, and a hurricane came in. He was staying at the house as he was rebuilding it,” Stansel says. That hurricane, according to Starkey’s book, was the September 1885 hurricane, which killed between 150 and 300 people—five to six percent of Indianola’s population—and nearly destroyed the town entirely.

Slover, trapped inside the house, had to make a dramatic escape. “It flooded everything, and he had to crawl up in the attic of the house and the water was still coming in,” Stansel says. “So he had to chop a hole in the roof and crawl out on top of the roof, and then he was rescued by somebody in a boat.” Slover had not yet built a successful home, perhaps, but he had surely demonstrated his insurmountable grit. That grit would be tested again, in 1900, when a home he had been building in Velasco, Texas, West of Galveston, was destroyed during the September hurricane. Slover salvaged lumber from the storm and relocated to Alvin, where he purchased a third of an acre of land. He was 66 years old and ready to begin the project that would define his life’s work.

The cottage itself, built in the Victorian Queen Anne style, was originally a three-room structure with siding made from cypress. Later, Slover would add two turrets, additional rooms, and a bath. The cottage’s impressive details include 10 ½-foot ceilings, extensive trim work, pocket doors, gingerbread molding, and a sunroom.

While the cottage shows off Slover’s handiwork, he did get a little decorative help. “We feel pretty comfortable that he purchased a few of the moldings,” Stansel says. “Some of them probably came off other Victorian houses.” Many of the home’s other pieces, Stansel says, were clearly made by hand. “You take a look and it’s definitely stuff that he cut and put up there, because you see—not major flaws, but slight flaws,” he says.

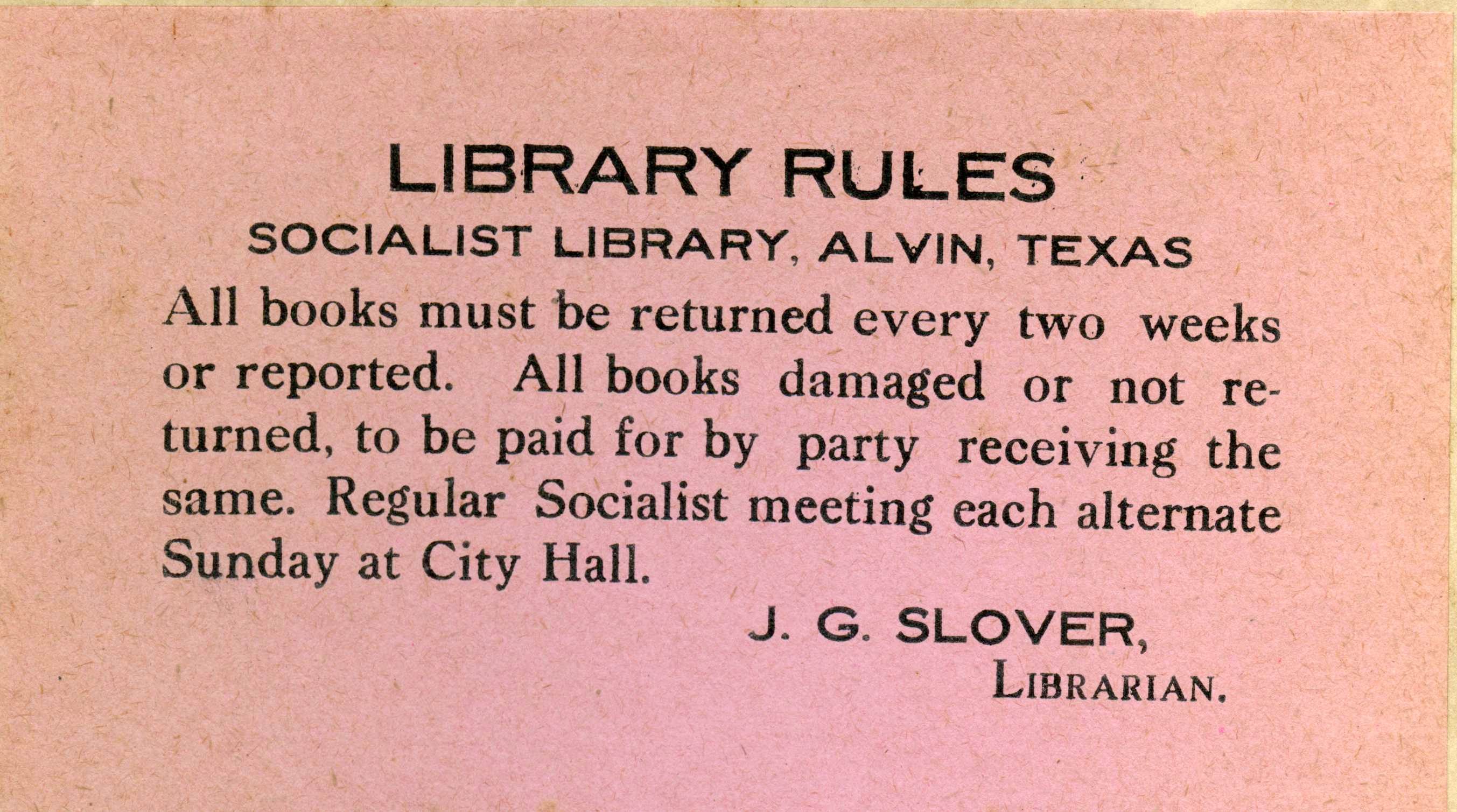

Outside, Slover planted Satsuma orange trees, fig trees, and kumquats. The home also boasts a small ancillary library, used for Slover’s collection of Socialist literature. Dutch doors served as a library window, and a sign for the library, according to Starkey’s book.

Slover had five wives; his first wife died before he moved to Texas, and he remarried multiple times after her death. “The house originally had a bathing room in the house and an outhouse out back. After Slover’s death, his last wife remarried and wanted to have an indoor commode,” Stansel says. “Her new husband put her off as long as he could, because he said it was unsanitary to do your business in the place where you sleep.” When she finally convinced him to add the commode, he stubbornly refused to use it.

At age 89, separated from Mary Elizabeth Potter, his final wife, John Slover moved in with his son, Burt. One evening in July, following a trip to the movies, he began a mile-long walk to his son’s home, where he suffered a fatal heart attack. But Slover’s legacy in Alvin remains: Visitors can step inside this 1100-square foot cottage, which offers a window into one veteran’s contribution to the soul of a small Texas town.

This post is sponsored by Visit Alvin. Click here to explore more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook