The Hidden Meaning of Political Bumper Stickers

What does the slogan on your car say about you?

Bumper stickers on sale at an anti-war protest. (Photo: Patricia Marroquin/shutterstock.com)

Whether it’s “Yes She Can” or “Hillary for Prison,” it’s hard to take a drive anywhere in the United States without coming up on at least a few different political bumper stickers. Some are official campaign gear, others are custom designed, some are picked up at rallies and protests, but they all serve the same purpose: to let whoever chances upon your bumper to know where you stand politically.

The bumper sticker’s invention is largely credited to Forest P. Gill, a silkscreen printer from Kansas. Gill invented a sticker designed specifically to stay attached to a car’s bumper in the late 1940s, and it didn’t take long for the bumper sticker to become wildly popular. By the 1950s, all types of bumper stickers could be seen affixed to cars across the United States.

The first political bumper stickers were printed en masse in 1956, when Dwight Eisenhower battled Adlai Stevenson for presidential reelection (“I like Ike” was an immensely popular slogan on bumper stickers and campaign buttons for both Eisenhower elections). These days, political bumper stickers run the full gamut of slogans, from a simple “Hope,” indicating support for President Obama, to a feisty “You are NOT entitled to what I have earned”, to mark a voter’s opposition to taxpayer-funded welfare disbursements.

Indeed, bumper stickers can express the full range of Americans’ political sentiments in a very limited amount of space. They are also more popular here than in any other country.

Political bumper stickers are a surface-level and necessarily simplistic form of communication (they leave only a few square inches to work with), and while they may seem like aesthetic clutter on the back of a car, there’s a lot more going on, both psychologically and ideologically, with political bumper stickers than mere campaign slogans.

Jack Bowen, author of If You Can Read This: The Philosophy of Bumper Stickers, says that bumper stickers are a simple way for people to literally take their voices to the streets without actually speaking. Bowen spoke with Atlas Obscura to reveal the role political bumper stickers play in political culture, and why we love them.

What sort of person is inclined to use political bumper stickers?

People who are impassioned tend to share that passion on their bumpers. People who are really committed to their political cause want to get that cause out there and heard. Bumper stickers are a good way to do that.

Additionally, political party affiliation and approval—or, in many cases, disapproval—of candidates puts one in a group, and gives a sense of belonging. So there’s this sense of being “in” with bumper stickers. Good campaigns, just like good advertising, sell an image. People loved Obama’s “Change” campaign and wanted to jump on board: it was fun to be “in.”

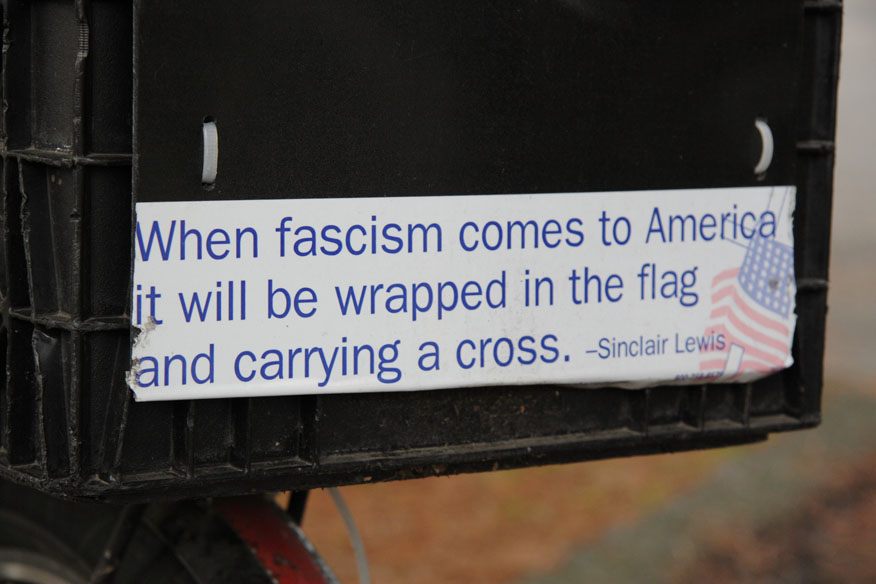

A humorous political sticker. (Photo: Mike Renlund/CC BY 2.0)

What’s the appeal of using cars as vehicles of political expression?

We all know the guidelines about avoiding any discussion of ethics, politics, or religion at dinner parties. But the car is a perfect place to have this “discussion” and to voice your position. You can say, “We Need Change,” or, “Keep Your Change” and not have to engage in what often turns out to be a fruitless and hotly contested argument.

This all taps into the way we think through our moral and political intuitions. Recent psychology and neuroscience have shown we go through this process in a way we’re not wholly conscious of. We first intuit a conclusion—i.e. immigration is bad, or a certain method of taxation is unfair—and only then, in some post hoc manner, fill in reasons for that emotionally-based conclusion. Bumper sticker slogans do a good job of being emotional conduits.

A more general political bumper sticker. (Photo: Robert F. W. Whitlock/CC BY 2.0)

How do political bumper stickers contribute to our political discourse?

The ability to make a rich statement in a few words, is, at the very least, a starting point. Such as with “Deport Trump.” With this sticker, in two words you’ve said “I’m not voting for Trump,” and “I have a concern with how Trump is talking about immigrants.” You’ve actually said paragraphs and paragraphs, and now we can come back and have a conversation.

The bad news is, for very few people is this a starting point from which they’re then going to delve into the crux of the matter and look at logic and data. A lot of times, the sticker is the end of the conversation.

Political bumper stickers make bold statements, but from within the shelter of a car. What do you make of the loud but anonymous communication achieved through bumper stickers?

When people are in their cars, they behave in a way that they never would if a pane of glass and piece of metal weren’t there keeping them a foot away from the person sitting next to them. I kind of like that. It’s a chance for someone who is more introverted who isn’t engaging in public discourse to say what they think and why they think it.

The problem is, again, that it doesn’t allow for real discourse. It’s like shouting at someone, then putting headphones on and walking away. It’s not a conversation.

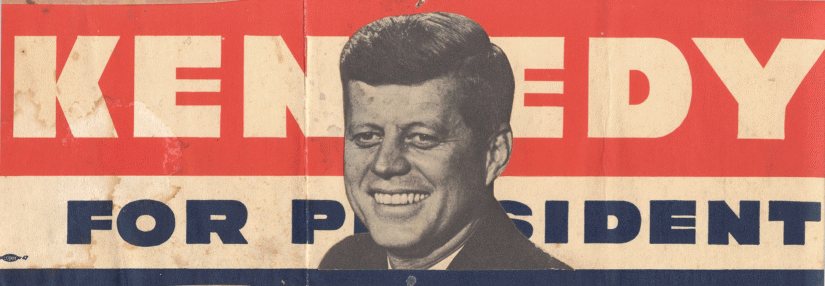

Kennedy’s bumper sticker from his campaign. (Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Public Domain)

Kennedy’s bumper sticker from his campaign. (Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Public Domain) It’s been argued recently that political bumper stickers are going out of style. Are bumper stickers waning in popularity or do you think they’ll remain with us as long as we have elections and cars?

People now have so many other venues to voice similar ideas. With social media, the tweet has taken over for people’s itch once scratched by the bumper sticker. Now you can just “yell” something out at those following you in 140 characters and you don’t really need to defend it. Given that users tend to be connected with like-minded people, their emotional tanks get filled rather neatly by likes and shares. Aside from the occasional honk-plus-the-finger or thumbs-up, you don’t get that kind of feedback with bumper stickers.

Additionally, cars just aren’t being made with bumpers any more as the car frame just extends down more than it used to, so there’s no bumpers for stickers on cars now.

A bumper sticker from Gerald R. Ford’s 1976 campaign. (Photo: Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum/Public Domain)

There are people who plaster tens of political stickers on their bumpers. What do you think is going on there?

All 150 claims they’re making on their car, they’re not expecting for you to digest what they think about abortion and taxation and euthanasia. They’re framing an ideology from an emotional position. I don’t have bumper stickers on my car, but I get how someone can get to the point that they’re so impassioned, that these messages are sort of what they’re screaming out to the world, even though they know that nobody is reading every sticker.

It’s hard for me to imagine they’re hoping to enact some kind of change or discourse; it’s like a person who wears a vibrant tie-dye shirt instead of a crisp white button-down shirt.

Mitt Romey campaign stickers from 2012. (Photo: Daniel Oines/CC BY 2.0)

What do you make of drivers who leave political bumper stickers on their car well after they’re relevant? I still see “Kerry for President” stickers out there…

There’s a kind of nostalgia that goes with these stickers. Like, “Those were the days!” when Reagan or Jimmy Carter was running for president. When you put a Jimmy Carter sticker on your car and leave it there for 20 years, you’re saying something about who you were, but also about who you are now. You still stand for whatever values you and society associates with Jimmy Carter.

What makes a great political bumper sticker?

Good stickers require a little background knowledge and also some connection to previous memes, but also get the point across in very few words. Some of stickers that do this the best for this election season are: Hillary For Prison 2016; Liar, Liar! Pantsuit On Fire; Deport Trump; Trump: Making America Hate Again; Yes She Can; and Obama, You’re Fired!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook