The History of Fake Meat Starts With the Seventh-Day Adventist Church

Breathing exercises, an example of the healthy living espoused by John Harvey Kellogg at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, Michigan. (Photo: Cbl62/ Wiki Commons)

Breathing exercises, an example of the healthy living espoused by John Harvey Kellogg at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, Michigan. (Photo: Cbl62/ Wiki Commons)

Veggie burgers and imitation meat are downright common these days, but it took a long time for meat analogues to earn respect at the table.

But eventually, it happened. These days, fast food chains like Burger King and Subway sell veggie patties. The veggie dog is common in most baseball parks—both minor and major league—and if you’re on one of the coasts, it’s not too hard to find a restaurant that’s willing to sprinkle a little Gardein onto your nachos in lieu of the ground beef. Research by Mintel in 2012 showed that the meat alternatives industry was worth a whopping $553 million in the U.S. alone.

But this whole business of fake meat becoming really popular didn’t come out of nowhere. For that, we have 19th-and-20th-century adherents of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church to thank.

The church, a Protestant sect that encourages members to practice vegetarianism, had a prominent adherent in the form of John Harvey Kellogg.

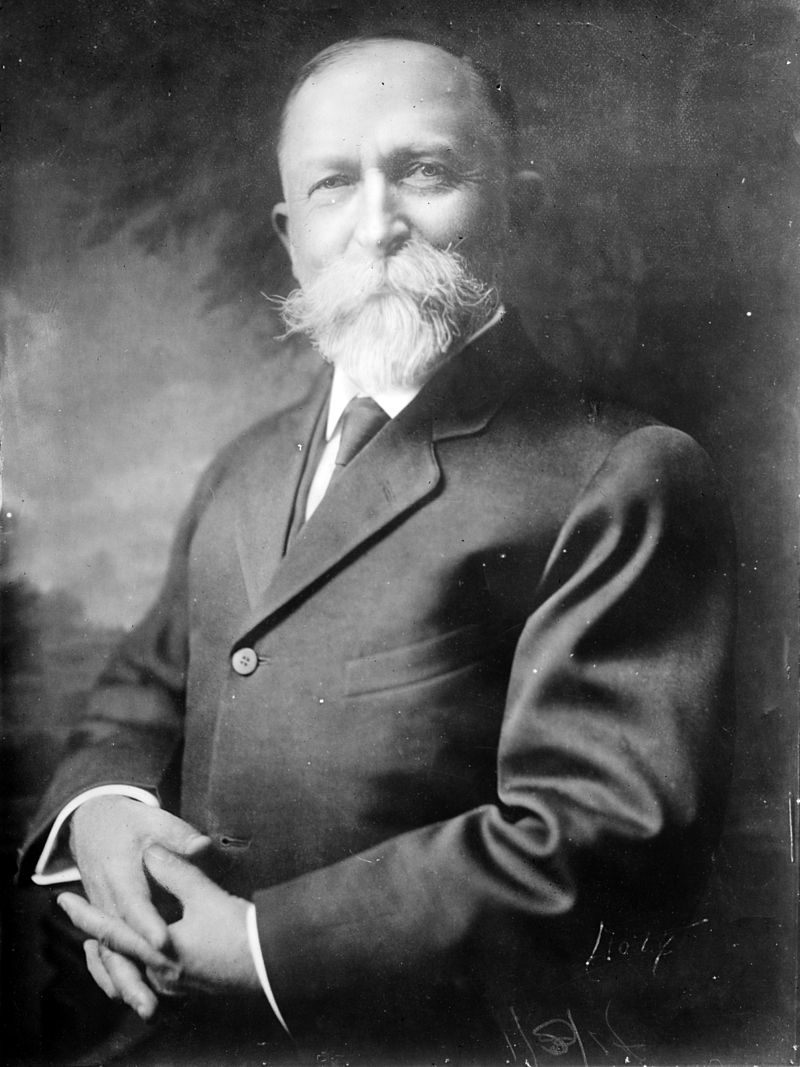

John Harvey Kellogg, one of the forefathers of making cereal part of a complete and healthy breakfast. (Photo: Library of Congress/Wiki Commons)

John Harvey Kellogg, one of the forefathers of making cereal part of a complete and healthy breakfast. (Photo: Library of Congress/Wiki Commons)

Kellogg, now of supermarket aisle fame, was a well-known health advocate in his hometown of Battle Creek, Michigan. He initially started experimenting with meat analogues as a way to assist local residents in sticking to their vegetarian diets. Kellogg soon opened the Battle Creek Sanitarium, a health resort which emphasized the value of healthy living based on Adventist principles. While experimenting with different kinds of food, he managed to invent the modern form of cereal basically by accident.

John Harvey and his younger brother, Will Keith, discovered that some boiled wheat they left lying around flaked up really well. The older sibling was on the hunt for foods good for chewing, which he considered a way to help indigestion and tooth decay, and decided to offer it to Sanitarium residents. It didn’t even strike the duo, however, that the toasted wheat flakes might be a fitting breakfast food—until, that is, the Sanitarium residents got a hold of it and added milk.

In the process of Toasted Wheat Flakes’ sudden success, John Harvey got into a bitter feud with his more traditional brother—who eventually turned those cereal products into a hugely successful company, minus the heavy focus on health care.

But while the older Kellogg was feeling spurned, he found an opportunity to create a company of his own, the Battle Creek Food Company. This company focused almost entirely on fake meats, with perhaps the best known of the time being something called Protose.

That product—a combination of wheat gluten, peanuts, and soy—was one of the first efforts to create a meat analogue in the modern era. While pure wheat gluten (now known as seitan) and soy bean curd (better known as tofu) have been around for generations, Kellogg’s effort proved fairly inspirational in the conception of fake meats as we think of them now.

A Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Indiana. (Photo: Nyttend/Wiki Commons)

A Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Indiana. (Photo: Nyttend/Wiki Commons)

While John Harvey Kellogg created the seed, it was the work of another group of Seventh-Day Adventists that turned his creation into something resembling burgers and hot dogs. A few fans of Protose in Worthington, Ohio came up with the idea of making the veggie foods more realistic-looking, and using seasonings similar to meat. (One of those innovators, Dr. George Harding, was a relative of Warren G. Harding. It remains unknown whether the former president–or his secret family–ever tasted a fake steak.)

These early efforts led to the creation of Worthington Foods, which released two canned imitation meat products in 1949: Soyloin Steaks and Meatless Wieners. If you want to check out what midcentury veggie meat tasted like, you can still buy a variation of Meatless Wieners today, sold in packs of 20-ounce cans.

After a few decades of Worthington’s early work on this front, they ended up selling the company to a firm called Miles Laboratories. That firm launched a sister company whose name you might recognize: Morningstar Farms. Morningstar took the groundwork from Worthington’s patents and created a line of products, like the famous Chik Patty, that finally took off in the mass market.

Over the years, Worthington changed hands again multiple times—eventually, coming full circle by falling into the hands of its former blood rival, the Kellogg company. Earlier this year, Kellogg palmed Worthington off on a natural foods company, but held onto the successful Morningstar Farms brand.

While veggie burgers have become a relatively simple way for restaurants to cater to the 3.2 percent of Americans that are vegetarians, it took nearly three-quarters of a century to get them on board.

A modern veggie burger. Delicious. (Photo: divinemisscopa/Wiki Commons)

A modern veggie burger. Delicious. (Photo: divinemisscopa/Wiki Commons)

The groundwork for was laid in 1895, with the founding of “Vegetarian Restaurant No. 1” by New York City’s Vegetarian Society. On its first night, the restaurant served fruit soup and Graham bread—the latter being a good fit, due to the fact that Graham crackers were originally invented as a form of vegetarian fare.

But while these efforts grew in earnest, with eateries such as the Schildkraut chain of 15 NYC-based vegetarian restaurants (run by husband and wife team Herman and Sadie Schildkraut) and Chicago’s Mortimer Pure Food Café gaining momentum, they ultimately struggled to sell to Middle America.

Reputations were even ruined in the pursuit of making vegetarian food appeal to a crowd that wasn’t ready for it. In the late 1920s, William Childs, a vegetarian who had built one of the country’s first national restaurant chains, tried to move his company to an all-vegetarian menu. His aim? To encourage better health for his customers and not burden their wallets in the years leading up to the Great Depression. That plan didn’t work out so well for him, and after some disastrous sales, he lost control of the corporation.

Simply put, the broader culture hadn’t caught up, not even in New York City, where many adherents of vegetarianism were Jews doing it for religious reasons. During World War II, even The New York Times took jabs at vegetarians, especially around the turkey-stuffed holidays.

“Even the vegetarians are preparing to be bold trenchermen this Thanksgiving, although without the benefit of turkey, stuffed or otherwise,”the newspaper wrote in 1941 about a dinner held by the Vegetarian Society of New York.

Perhaps William Childs and Sadie Schildkraut were simply early to the game. The big turning point came in the early 1960s, when in London, an all-vegetarian restaurant called Cranks launched in 1961.

It proved hugely popular with the public at large and was seen as a major influence in the rise of vegetarianism in the U.K., soon attracting big-name celebrities like Linda McCartney and Princess Diana.

Japanese style tofu, a mainstay of the modern vegetarian diet. (Photo: Drypot/ Wiki Commons)

Japanese style tofu, a mainstay of the modern vegetarian diet. (Photo: Drypot/ Wiki Commons)

While the restaurant got things moving, it didn’t stick around long enough to see the trend all the way through: The chain, which had struggled to shake off its hippie-ish image, mostly closed up shop in 2001 and lives on as a line of boxed sandwiches with colorful names such as Eggstacy and Hey! Pesto.

The problem with veggie food these days is not the abundance of it, but whether those mass-marketed imitation burgers and dogs meet the high levels of health-food consciousness that consumers expect.

Kellogg’s is actually seen as sort of the bad guy in this case—now owning Morningstar Farms, the company has taken to using genetically modified organisms in its food a little more aggressively than many of the products you might find at Whole Foods. In 2001, Greenpeace called out the company after it found that some of its soy-based meats had a large percentage of GMOs.

The company said it was an accident, but Greenpeace didn’t buy the defense.

“It’s very hard to explain 50% of the soy [in a product] being genetically engineered as just a slip up,” Greenpeace’s Charles Margulis told the Los Angeles Times. “This seems to be a company that just doesn’t care.”

More recently, a 2014 study from Consumer Reports found that two varieties of Morningstar Farms fake meats tested positive for GMOs, along with a variation of Boca Burgers. If you don’t like your foods with GMOs baked inside, your options might be a little more limited.

It’s safe to say we’ve come a long way from John Harvey Kellogg and Protose. Kellogg’s itself stopped making Protose back in 2000, around the time that Kellogg purchased Worthington.

Early Kellogg’s Corn Flakes advertisement (Photo: Wiki Commons)

But that hasn’t kept some enterprising folks from making their own versions of the seitan, peanut, and soy mash-up. One person who has gone out of their way to create it says it’s tasty, but mushy; another was non-plussed about the result the first time around but loved it after trying again.

If you don’t want to go to the trouble of mixing your own soy, peanut butter, and gluten together, there is one other option: Another company that traffics in imitation meat, Cedar Lake, produces a food called Proteinut, which is about as close as you’re likely to get without traveling in time to stay at the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

It’s hard to get the real deal when you’re eating fake meat.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook