The Most Remarkable Globe in The World Is in a Brooklyn Office Building

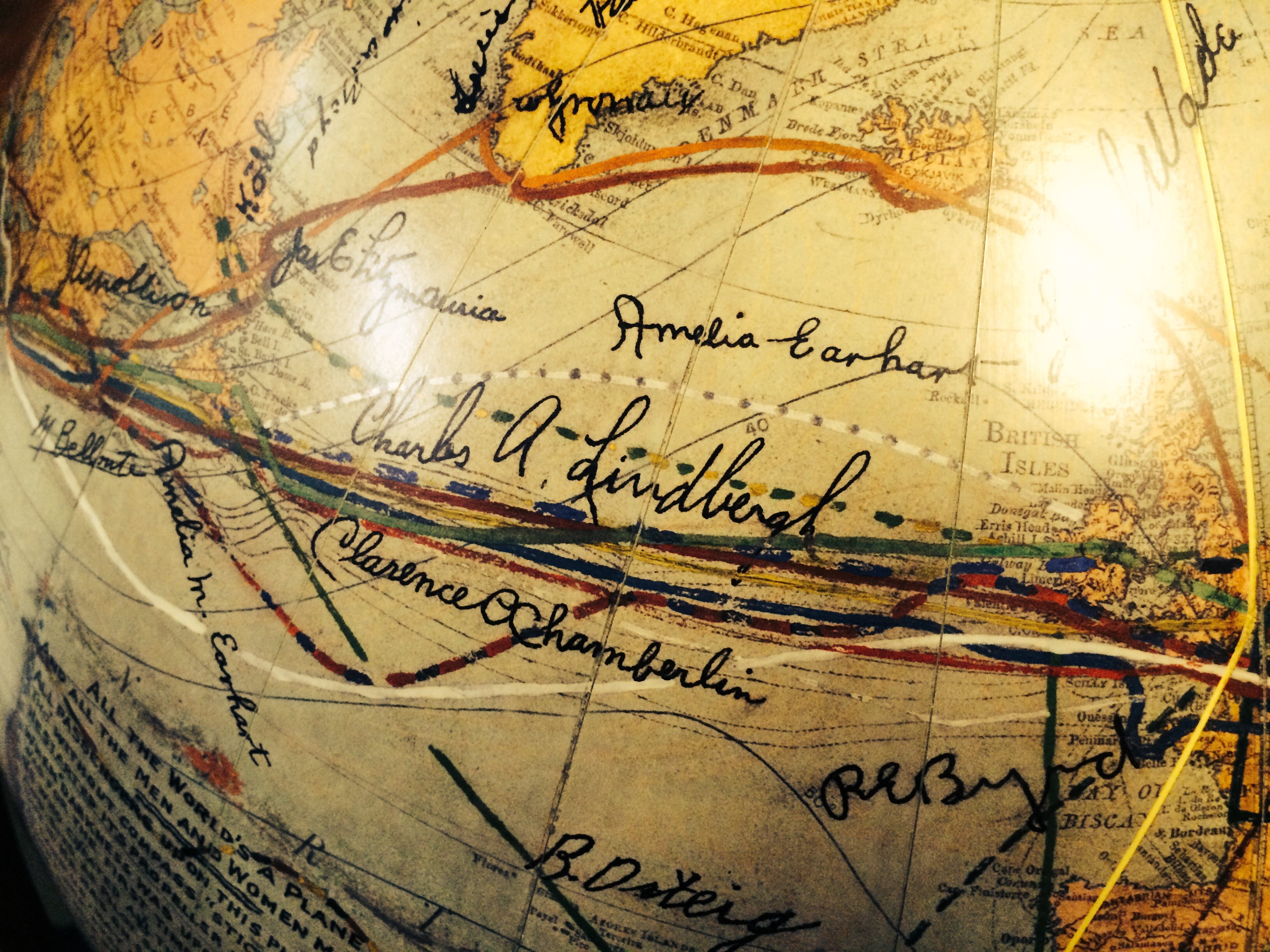

Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart’s signatures on The Fliers and Explorers Globe (Photo by Luke Spencer)

On the second floor of a nondescript office building in downtown Brooklyn, behind a plain wooden door at the end of the hall, you’ll find one of the world’s most wonderful artifacts of exploration and adventure: the Fliers and Explorers Globe.

The crowning glory of the now-modest headquarters of the American Geographical Society, the globe is just a standard schoolroom model. But it has been signed by virtually every famous aviator and explorer in modern history. From Amelia Earhart to Charles Lindbergh to Sir Edmund Hillary, the heroes not only signed their names but also drew their routes upon the globe.

The office of the American Geographic Society in Brooklyn. (Photo by Luke Spencer)

The tradition of signing the globe originated in 1929 with John H. Finley, then both president of the American Geographical Society and editor-in-chief of the New York Times. Often Finley himself would go down to the docks of Lower Manhattan to personally greet the returning adventurers and have them trace out their routes across the Earth.

The purpose was, as the Society puts it, to create “a priceless and unique symbol of humanity’s unquenchable drive to explore the universe.” There are currently 82 signers on the irreplaceable globe, and the tradition is ongoing, with AGS adding a new explorer every year. Recent signers include Russian Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, who in 1965 was the first human to walk in space. This year’s signer will be film director James Cameron, for his unparalleled achievement in reaching, in his one-man submarine, the deepest point in the ocean, the Mariana Trench.

To find such a treasure virtually undetected in a small office in Brooklyn is quite peculiar. But the American Geographical Society wasn’t always so obscure. At one time, it lived in a magnificent neo-classical building in Washington Heights, and was one of the celebrated institutions of its age. In 1851, Sir John Franklin’s doomed expedition to find the Northwest Passage had been missing for four years. Following Lady Franklin’s desperate pleas for help, a group of likeminded adventurers came together in New York to form the American Geographical Society, with the purpose of funding and carrying out a rescue mission to the Arctic.

From the very beginning, the Society was made up of an equal mix of scholars, businessmen, and government officials. The mission to find Lord Franklin was unsuccessful, but the Society grew in stature and influence. Current executive director John Konarski III explains that, “in the 1850s educated people in New York would get together after dinner to discuss geography. It was important at the time, especially with the railways heading west, and the common interest of railway company members who served on the board.”

For decades, the Society was the principal map resource of the United States. The office displays a 10-foot long photograph of the Trans Continental Excursion of geographers who traveled to the West Coast and back in 1912, mapping the country. Following the 1918 Armistice, Woodrow Wilson prepared for the Paris Peace Conference at the Society headquarters, drawing upon its unparalleled collection of maps and data. Until the end of World War II the AGS contractually made all the maps for the government, and kept a permanent staff of over 80. But that ended after the war.

As the government revenues disappeared, the AGS became dominated by academia and found itself heading towards bankruptcy. The old headquarters was sold in 1970 and the Society eventually found itself in the small rental office in Brooklyn and on the verge of disappearing into history.

After visiting the globe, my next port of call was Broadway and 156th Street in Washington Heights, and the ornate limestone original home of the Society. Part of Charles P. Huntington’s Beaux-Arts masterpiece, the eight-building Audubon Terrace complex, the building was as grand as any of New York’s museums, with giant classical columns and a rooftop frieze decorated with Marco Polo, Vasco de Gama, and other great explorers. The building housed the Society’s archive of atlases, journals, and photographs, the world’s largest collection of maps, and the Fliers and Explorers Globe.

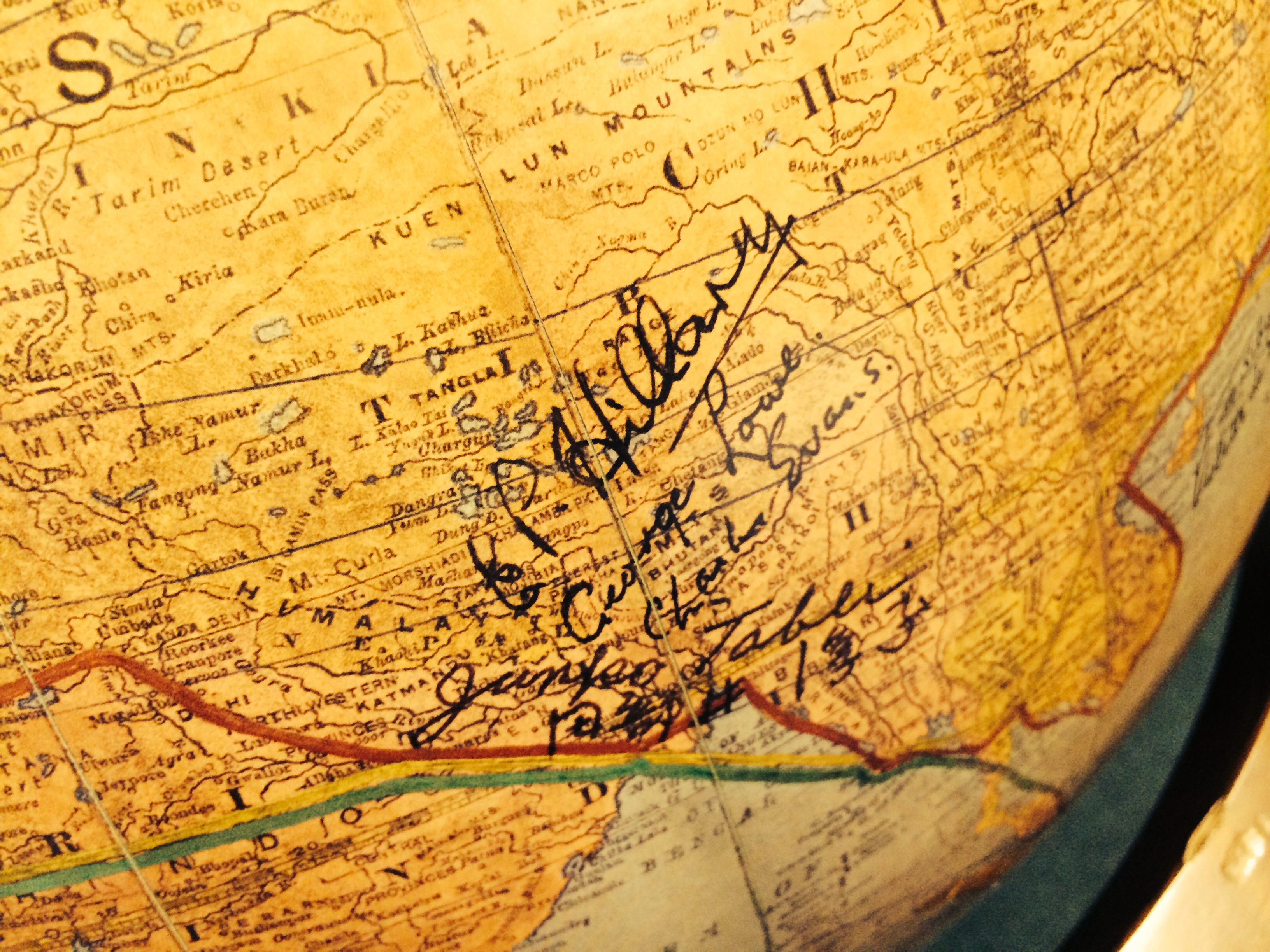

Sir Edmund Hillary’s signature on The Fliers and Explorers Globe (Photo by Luke Spencer)

Since 1970, the building has been home to Boricua College, a centre of Puerto Rican education. But the main entrance is still carved with the name American Geographical Society. Above the door is a huge stone globe bearing the society motto “Ubique,” meaning “everywhere.” The giant brass doors are magnificently decorated with oversized compasses. Inside the college, remnants of the old Society are everywhere; from the original elevators stamped with the AGS initials, to the cast iron stairs with globe balustrades. In one of the schoolrooms on the ground floor, the back wall is dominated with a giant map of South America, a leftover from the Society’s effort to map the entire world.

The original headquarters of the American Geographical Society (Photo by Luke Spencer)

It’s sad that such a magnificent organization, with such an incredible collection, has nearly disappeared. Back in Brooklyn, Konarski explains that the “nature of old organizations is that they acquire a lot but are not necessarily skilled in dealing with it.”

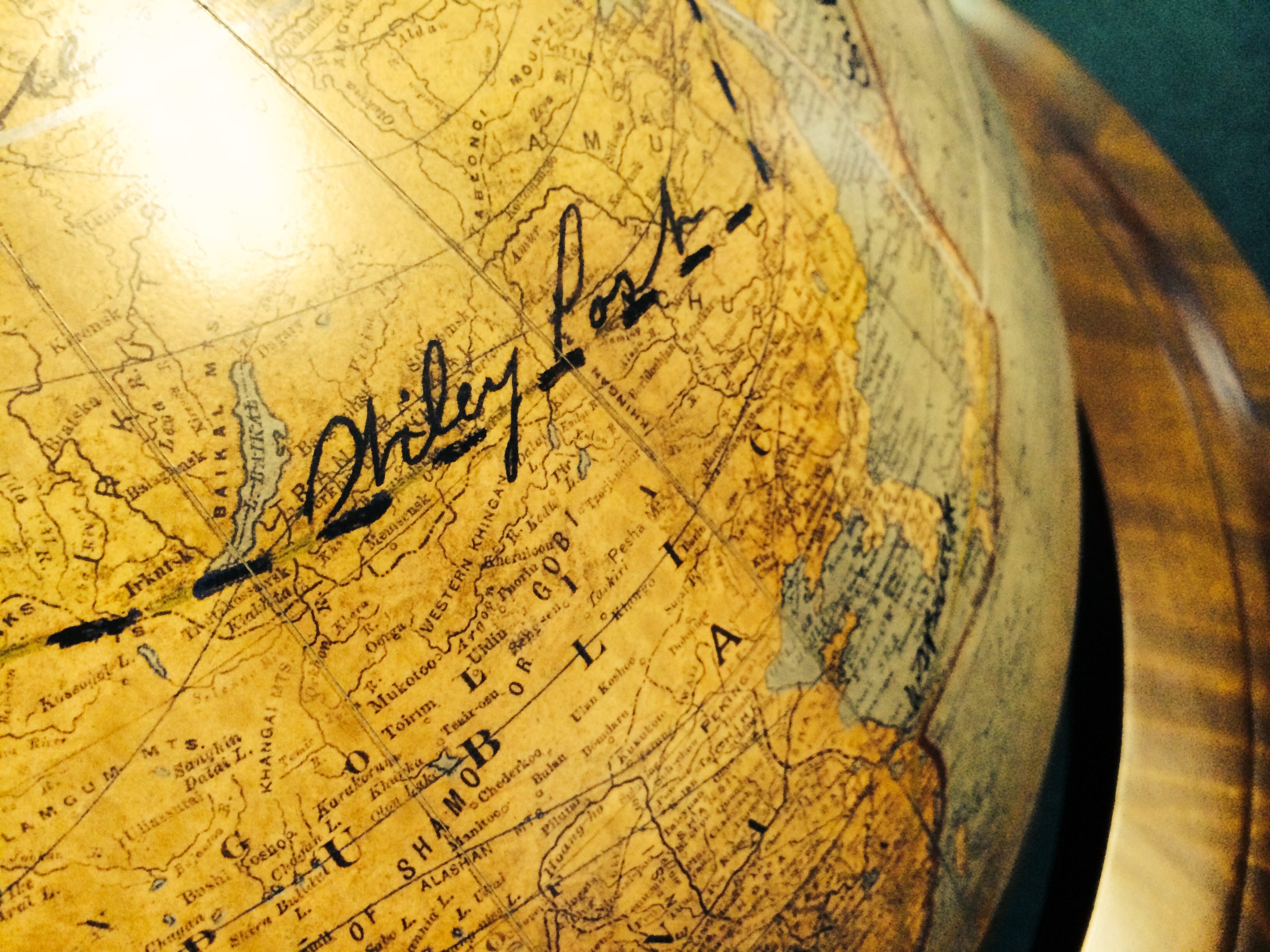

The strangest and most poignant aspect of the Fliers and Explorers Globe is that no one ever sees it. No one sees the route of Wiley Post, who in 1933 was the first to fly around the world; the signatures and paths of Robert Peary, the first man to the North Pole and Roald Amundsen, first to the South Pole. “It sits in my office and no one sees it,” says Konarski. “I’d like to get it into the public.” Under his stewardship, the Society is already beginning to show signs of revival, pioneering work in geospatial analysis. Plans include a move back into Manhattan, this time to the redeveloping South Street Seaport neighborhood, back to where the Globe’s originator, Finley, would greet the returning explorers.

Wiley Post’s signature on The Fliers and Explorers Globe (Photo by Luke Spencer)

And what of its original archives? After the Audubon headquarters was sold in 1970, the prodigious collection was presented to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Library on permanent loan. Today, the collection of over 1.3 million artifacts is housed in its own wing, where it is actively curated and added to. Like the Fliers globe, this incredible resource is hardly known about outside of geographical academia. It contains such treasures as the 1452 Mappa Mundi by Venetian artographer Giovanni Leardo, the original manuscript maps of Captain James Cook, more than 10,000 atlases, and some of the oldest globes in the world. Armed with an introduction from Konarski, I’m heading there next…

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook