The Parting Gifts Convicts Gave Loved Ones Before Being Shipped to Australia

A convict love token from the collection at the National Museum of Australia. (Photos: Katie Shanahan/National Museum of Australia)

In 1818, a teenage boy in London gave a memento to his parents. The sentiments expressed on each side of the copper token are impassioned, and with good reason: the gifter, 15-year-old John Camplin, had just been caught stealing a watch and sentenced to “transportation for life.” He would never see his parents again.

The token read:

Dear Father Mother

A gift to you ~

From me a friend

Whose love for you

Shall never end

when this you

See Rembr me when

In som Foreign

Country

Transportation sentences were fixed at a duration of seven years, 14 years, or life. That said, even a seven-year sentence usually meant a one-way ticket to the United States, or later, Australia—convicts rarely had the means to return to Britain after serving their time.

After a convict had been found guilty and sentenced to transport, he or she would be kept in prison until a ship was ready to depart from the south coast of England. These last few days, weeks, or months in Britain were the final chance for convicts to see their loved ones before being separated forever.

Some convicts went beyond hugs, kisses, and words of farewell and created custom mementos to leave with a family member, wife, or lover. A cheap and readily available way to make one of these personalized gifts was to take a 1797 “Cartwheel” penny or twopence, scratch off the head of King George III, and stipple or engrave initials, words, dates, or pictures. These mementos, often created in prison, are known as “convict love tokens,” or, in the poetic phrasing of Newgate Prison history chronicler Arthur Griffiths, “leaden hearts.”

The American Revolution had a big impact not just on the inhabitants of the Thirteen Colonies, but on the lives of convicts in London. Prior to 1776, a convict sentenced to seven years’ transportation for stealing silk handkerchiefs or pickpocketing a watch would be bundled onto a ship with hundreds of other criminals and sent to one of the British Empire’s American colonies to serve time.

With the signing of the Declaration of Independence, that all changed. Instead of being dispatched across the Atlantic, British convicts were packed into the overcrowded cells of Newgate Prison in London or crammed by the hundreds onto typhoid-riddled ships moored in the Thames. It was an untenable situation.

However, the government had another, newly charted option on the horizon: Australia, where the first colony was established in 1787. They wanted their convicts to provide free labor to develop the country. The voyage was significantly more harrowing than crossing the Atlantic: Australia was over 11,000 nautical miles from England, literally on the other side of the world.

Ships from the First Fleet arriving at Port Jackson in Sydney in January 1788. (Image: State Library of New South Wales/Public domain)

The first convict voyage to Australia took place in 1787. Eleven ships, collectively known as the First Fleet, brought more than 700 convicts to Sydney, accompanied by several hundred other passengers such as marines, government officials, and crew members. The ships departed from Portsmouth, England on May 13, 1787, and arrived in Australia between the 18th and 20th of January, 1788—a journey of over 250 days. Conditions were trying: aboard the Alexander, for example, 15 of the 195 convicts died of illness along the way. In a journal entry dated July 18, 1787, John White, Surgeon-General to the First Fleet, wrote about the poor conditions on the Alexander:

“[I]llness complained of was wholly occasioned by the bilge water, which had by some means or other risen to so great a height that the pannels of the cabin, and the buttons on the clothes of the officers, were turned nearly black by the noxious effluvia. When the hatches were taken off, the stench was so powerful that it was scarcely possible to stand over them.”

A “Cartwheel” tuppence. (Photo: Detecting on Wikipedia)

The world’s largest collection of convict love tokens is held by the National Museum of Australia, located in Canberra. It consists of 314 tokens, 307 of which were acquired in 2008 from British antique dealer Tim Millett.

Millett first stumbled upon convict love tokens while working at his family’s coin dealing business, AH Baldwin & Sons, in the early 1980s.

“I started [the collection] with about 10 that I found, bits of pieces here and there,” he says. “I thought, this is much more interesting than mint-state gold coins.”

Among numismatists, convict love tokens don’t hold much appeal. When Millett began to be known for collecting them, dealers would send tokens his way, but didn’t understand his interest in a bunch of scratched-up, low-value coins.

“It was rather along the lines of, ‘Oh God, there’s that nutcase Tim Millett who’ll pay good money for these things.’” Millett says. “The trade always regarded them as a bit of a nonsense.”

Love tokens given between members of a couple have long been a phenomenon. “Convict love tokens are an off-shoot of a much earlier tradition of exchanging tokens between lovers or family members who must part, which became increasingly popular from the 17th to the 19th century,” writes Rebecca Nason in a 2009 article on the tokens for the Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia.

A 1789 illustration of First Fleet prisoners arriving in Sydney. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

For Millett, however, the convict versions held a particular intrigue. Tokens made by prisoners can be difficult to track down. One reason is that, due to a lack of identifying information, they are often not recognizable as artifacts of the convict transportation era. Though some prisoners used their full names and referred to their sentences explicitly in the messages they engraved on their coins, many used only initials—to give a paramour a keepsake that linked them with a convict was to invite shame.

Over the years, Millett began to scrutinize what looked like run-of-the-mill love tokens more closely, checking for convict clues. “What might appear to be just a couple of love tokens—which is really, even now, not worth very much—you’d just get a sense that there might be something more to it than that,” he says.

Millett did conduct research into the identities of the convicts whose tokens he amassed, but with information scant, and records not available online, it was difficult to track down the details. Over 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1787 and 1868, and with so many Johns, Williams, Jameses and Henrys in the mix, matching a coin to the right person was a daunting task.

The details that Millett was able to find, however, stuck in his mind. Asked about which of the tokens in the collection is his favorite, Millett is instantly able to recite the lines of verse engraved on the reverse side of convict Thomas Alsop’s love token:

The rose

soon drupes

& dies. the brier

fades away. but

my fond heart

for you I love

shall never

go astray.

Alsop was convicted in July 1833 at Staffordshire for stealing a sheep, the 21-year-old was sentenced to transportation for life. In January 1834, he arrived at Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) on a ship that held 400 convicts. According to the National Museum of Australia, Alsop attempted to abscond from his chain gang in July 1835, an offense for which he received 36 lashes. The misbehavior continued: “between 1836 and 1847 he committed numerous offenses including refusing to work, stealing cattle, representing himself as a constable, absconding and being found in bed with a female prisoner,” the museum says.

Thomas Alsop’s love token, engraved in 1833. (Photos: Katie Shanahan/National Museum of Australia)

Despite all the mischief, Alsop was granted a full pardon in February 1850. Then aged 36, he married 21-year-old Irish-born Sarah Eliza Kirk and had two children. Alsop died in 1891.

Alsop’s story, while fascinating, is not unusual. Below is a love token created by 19-year-old David Freeman in 1818, after he was sentenced to transportation for life for stealing a handkerchief:

David Freeman’s love token, front and back. (Photos: Katie Shanahan/National Museum of Australia)

The London Criminal Court proceedings of June 17, 1818 show that Freeman and his co-accused, John Clark, professed their innocence when hauled into the Old Bailey on the charge of theft. The court’s summary offers a stark look at the moment their lives changed:

CLARK’S Defence. I never touched it.

FREEMAN’s Defence. It was thrown into my hand.

CLARKE - GUILTY . Aged 27.

FREEMAN - GUILTY . Aged 19.

Transported for Life .

Freeman was transported to New South Wales in September 1818 on the Lord Sidmouth. The ship, packed with 160 convicts, reached its destination in March 1819. The only other piece of information available is that he was pardoned on January 1, 1841. There are no known records of Sarah, the girl or woman for whom he carved his love token.

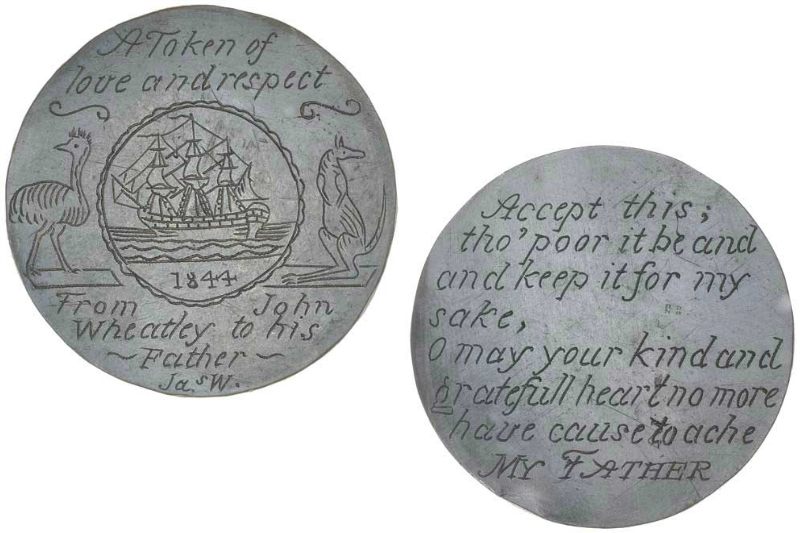

Though the digitization of records, such as the Old Bailey proceedings, has made researching the provenance of convict love tokens a little easier, numismatists still aren’t that interested in them. Individual tokens do sometimes sell for high prices, which can be baffling even to the coin dealers who put them up for sale. In November 2014, Australian coin dealer Noble sold an intricately engraved token made in 1844 at auction for $17,000. That price was $14,250 above the estimate.

“We do not know why it sold for so much,” says Nikki Kouis at Noble, while acknowledging that “it is an attractive piece.”

John Wheatley’s 1844 love token, which sold for $17,000. (Photo: Noble Numismatics)

Regardless of their monetary value, convict love tokens are valuable due to the clues they offer into what prisoners’ lives were like prior to their transportation.

“We know much about convict’s physical lives from documents such as prison records, ship’s logs, indents and tickets of leave,” says Dr. Sophie Jensen, Senior Curator of Australian Society and History at the National Museum of Australia. “However, we know so little about their actual lives – about their emotional lives.” The love tokens are uniquely intimate artifacts—evidence of the emotional upheaval convicts faced when sentenced to transportation.

At the National Museum of Australia, the process of matching convicts with their love tokens is ongoing. ”Thanks to the efforts of Timothy Millett and other researchers, we know the identity of convicts associated with approximately 80 of the tokens in the collection,” says Jensen. When a new match is made, it is cause for celebration.

“There is the constant excitement and satisfaction obtained whenever a single convict can be confidently linked to a particular token,” says Jensen. “When that link is made each particular token takes on a new significance—it becomes a tiny window into shattered or dislocated lives and the human side of the transportation story.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook