The Scandalous Decision to Pickle Admiral Horatio Nelson in Brandy

In the middle of the Napoleonic War, Britain’s most famous naval hero is struck by a fatal musket ball at the very moment of his greatest strategic triumph. Rather than bury his body at sea, a quick-thinking Irish surgeon preserves it in a cask of brandy lashed to the deck of the ship. A hurricane is on the horizon and the mast has been shot off; there is no way to hang the sails that would get ship (and body) to England quickly.

The two words that stand out in this story? Brandy and surgeon.

The scenario described is the death of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, a moment so central to Britain’s story of itself that in a 2002 BBC poll, Nelson placed number eight on a list of 100 Greatest Britons—slightly behind Elizabeth I and ahead of Sir Isaac Newton and William Shakespeare. His monument in Trafalgar Square, a 169-foot-tall column surrounded by larger-than-life brass lions, is such a key British emblem that Hitler planned to take it back to Berlin as a trophy once he conquered London.

Nelson atop his column in Trafalgar Square, looking over London. (Photo: RedCoat/WikiCommons SS BY-SA 4.0)

Nelson was barely less famous in his lifetime. Britain was an island nation with an overseas empire; the strength of its navy was central to national pride and economic security. Nelson was not merely a vice-admiral; was not merely the man beating the fearsome Napoleon’s fleet with aplomb and derring-do. Nelson was an officer who led from the front instead of the rear, who promoted men on the basis of merit instead of political connection, who referred to his missing arm as his fin, and flashed it at people who doubted his identity. His ongoing and blatant extramarital affair with a diplomat’s wife was tabloid gold that added an air of scandalous romance to his exploits.

News of Nelson’s death took 16 days to reach London; for the next two months, England was in a frenzy. The Times ran daily articles about Nelson’s demise and the homeward progress of his ship, the Victory, despite having little to report besides speculation. The eyewitnesses, after all, were still at sea, and electronic communication did not yet exist. Members of the public wrote so many poems of lamentation that the newspaper had to ask them to please stop sending poems (in both English and Latin, spawning all-Nelson anthologies like 1807’s Luctus Nelsoniani). Although nobody in England yet knew what had transpired in Nelson’s final moments, the Drury Lane Theatre staged nightly re-enactments. There was no escaping Nelson mania.

An entrance ticket for Nelson’s funeral. (Photo: Wellcome Images/WikiCommons)

A word about surgeons. For a modern reader, the title evokes respect. These are the cool-under-pressure miracle workers who can clean out a heart and rewire nerve endings. In the 1800s, not so much. This was pre-Ether Dome, a time not altogether removed from the barber-surgeon days; in the absence of anesthesia, most surgeons were essentially brawlers, burly guys who could hold you down or knock you out while they sawed and sewed. They often came from the lower classes (although this was less true in the navy than on land), and unlike the ship’s physician, were not typically invited to dine with the commissioned officers. Although the profession was trying to set up a system of accreditation, most of the public still viewed surgeons as a cross between butchers and sideshow performers, and they weren’t far wrong.

As it happens, Nelson’s surgeon, William Beatty, was exceptionally competent. At Trafalgar, 96 of 102 casualties treated by Beatty survived, including 9 of 11 amputees. For context, battlefield statistics collected in 1816 found amputation’s mortality rate in the best case scenario was 33 percent, and in less optimal conditions more like 46 percent. Beatty was not working in the best case scenario, according to Nelson’s Surgeon by by Laurence Brockliss, John Cardwell, and Michael Moss. He was in a small, poorly-lit cabin on a ship under attack, and then in a hurricane. To make matters worse, he was understaffed. Beatty’s staggering survival rate is all the more remarkable when you remember that Pasteur’s work on germ theory and Lister’s development of antiseptic surgery wouldn’t happen for another 50 years.

Sir William Beatty, surgeon, who was responsible for the preservation of Nelson’s body during the long journey back to England. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Beatty was also Irish at a time when Anglo-Irish relations were complicated. Although the two countries were firmly joined by the Acts of Union 1800 (creating the still-used Union Jack flag), that firmer union was a direct response to the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which was in turn a response to English brutality in Ireland. So although almost a quarter of the British seamen at Trafalgar were Irish, they were largely confined to the lower ranks. Meanwhile, there were plenty of Irish fighting on the French side, a whole legion of them waiting to invade the British Isles. Ireland was about as unified as Afghanistan.

So, looking at Beatty, you have someone outside the chain of command; who has no significant patrons or connections to institutional power; who is Irish. This is the person who takes charge of Nelson’s body—who is allowed to take charge of Nelson’s body—essentially because he was bold enough to say “I think I know how to do this,” and his co-workers trusted his skill.

Preserving a valuable corpse or scientific specimen in alcohol for transportation wasn’t unheard of in the 1800s; it’s a precursor to contemporary embalming practices. That doesn’t mean it was common. It’s not something most people would have direct experience with. But people were familiar enough with the idea that they had firm opinions about it. It was commonly known by members of the public that the best way to preserve a body was in navy rum, just like today we know you’re supposed to drink eight glasses of water a day, no matter who you are or what containers you use to measure a glass.

J.M.W Turner’s depiction of the Battle of Trafalgar. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

By keeping Nelson’s remains in brandy and ethanol—“spirit of wine” in the lingo of the day—Beatty was setting himself against popular wisdom. As a scientist, he knew Nelson’s body had the best chance of surviving the journey if he used the strongest proof liquor on board. But if it didn’t work—and there was no guarantee it would—standard rum was the politically safer choice.

Before he could be proven right or wrong, the ship had to limp its way back to England—grieving, wounded, jury rigged. And Beatty’s best impromptu efforts could only slow the decomposition of Nelson’s corpse, not arrest the process entirely. The body was slowly rotting. Two weeks into the journey, gaseous pressures burst the lid of the cask, startling one of the watchmen so much he thought Nelson had returned to life and was trying to climb out.

Nelson’s tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral, London. (Photo: Marcus Holland-Moritz/flickr)

Meanwhile, London was gearing up for the most lavish funeral celebration imaginable. Every coastal town in southern England was on alert to prep multi-gun salutes, militia parades, and black crepe street hangings “to turn out at a moment’s warning” if and when the Victory landed nearby. There was popular support to erect a huge Nelson monument under the central dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral. (They settled for a fancy tomb and a smaller statue by the wall.) On December 13, the Times ran an editorial imploring the public not to march a wax likeness of Nelson through town, “pageantry which borders upon childishness.” No rumor was too insignificant to print, and no monument too improbably large. The entire nation, regardless of class or occupation, was riveted.

When the Victory finally made port, it was inundated with a stream of visitors. If anyone on board had doubted the intensity of the public’s interest, it could no longer be in question. To prepare the body to lie in state in Greenwich, Beatty removed Nelson’s somewhat deteriorated pickled remains from the cask, wrapped them in clean linen, and transferred them to a lead coffin, again filled with brandy, as well as camphor and myrrh.

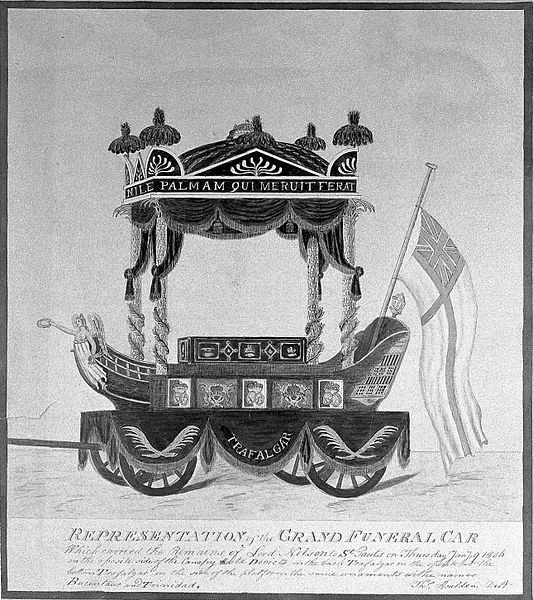

A depiction of Nelson’s “Grand Funeral Car”. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Mid-transfer, Beatty took the opportunity to conduct an autopsy, during which he recovered the musket bullet and a piece of gold epaulet—proof Nelson had been struck in the shoulder before the bullet lodged in his spine. Beatty wrote up his findings for the Admiralty and Nelson’s brother, but his primary objective wasn’t fact finding: he needed to empty out Nelson’s abdominal soft tissues, which were decomposing at a faster rate than everything else. Although Beatty would later claim the corpse was in perfect condition, both he and the chaplain wrote letters to their higher ups suggesting the face was by then a little too gruesome for public viewing.

After one final body shift, to a wooden coffin—Beatty cautious to make sure Nelson’s skin didn’t fall off in front of everybody—and a closed-casket farewell tour, London held a funeral which cost around $1.2 million, inflation adjusted. Nelson was buried. His corpse had spent 80 unrefrigerated days above ground. It was over.

The gossip wasn’t.

Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson painted by Lemuel Francis Abbott in 1799. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommon

Beatty was now famous, partly by his own doing. Why didn’t you use rum instead of brandy, people wondered, sometimes to Beatty’s face. Countless printed accounts said Beatty did use rum, because of course he did: it’s what you use. Popular slang popped up; navy rum was now “Nelson’s Blood.” Surreptitious tippling was “tapping the Admiral,” and legends abounded that the cask had been drunk down to nothing during the journey. (It hadn’t.)

In 1807, Beatty fought back with a bestselling book, Authentic Narrative of the Death of Lord Nelson, which let readers know in an authoritative third-person voice that all of his decisions had been exceptionally clever, and by the way brandy was the better choice. He returns to this point at least four times:

…a very general but erroneous opinion was found to prevail on the Victory’s arrival in England, that rum preserves the dead body from decay much longer and more perfectly than any other spirit, and ought therefore to have been used: but the fact is quite the reverse, for there are several kinds of spirit much better for that purpose than rum; and as their appropriateness in this respect arises from their degree of strength, on which alone their antiseptic quality depends, brandy is superior. Spirit of wine, however, is certainly by far the best, when it can be procured.”

A poster heralding the Battle of Trafalgar, and the “most renowned, most gallant and ever to be lamented hero Admiral Lord Viscoun Nelson”. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons

This worked and it didn’t. The Authentic Narrative became the go-to source for historians interested in Nelson’s final moments, and Beatty died wealthy—a king’s physician, and a knight. However, the Nelson-rum connection remains tenacious, with several liquor companies selling bottles of spiced rum named after the Admiral pickled in brandy. There are still pubs all across England called The Lord Nelson.

As for the killer musket ball, Captain Hardy (of “Kiss me, Hardy” fame) let Beatty keep it as a good luck charm. He used it as a watch fob for the rest of his life. When he died in 1842, his family gave it to Queen Victoria. It’s in the grand vestibule of Windsor Castle.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook