The Secret Messages Hiding Inside 17th Century Engagement Rings

They make the modern diamond ring look rather boring.

A gimmel ring at the British Museum. (Photo: Geni/GFDL CC-BY-SA)

When shopping for an engagement ring, the standard advice is to consider the four C’s: cut, color, clarity, and carat. In 17th-century Europe, however, the four C’s were a little different. Back then, those on the lookout for the perfect engagement ring had to consider consent, corporeality, concealed messages, and clasped hands.

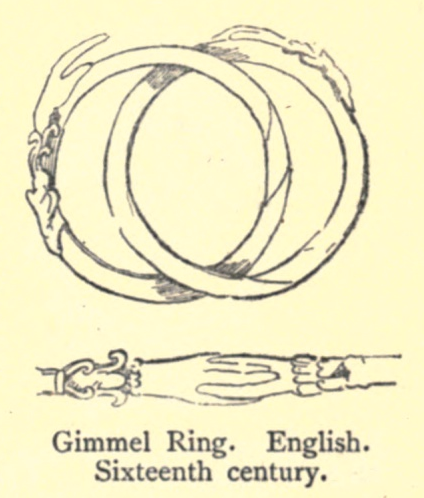

Gimmel rings, which rose to popularity during the Middle Ages, then enjoyed a heyday in the 1600s, consist of two interlocking hoops that, when connected, form one big fancy ring. Traditionally, the members of a newly betrothed couple would receive one hoop each. At the wedding ceremony, the two rings would be joined.

The name of this interlocking jewelry comes from the Latin gemellus, meaning “twin.” Sometimes the component rings were identical, and formed a symbol of unity when joined. A popular design was the clasped hands motif—each ring had one hand, and, when interlocked, the hands held one another. Other rings were not identical, but complementary, such as a design featuring a heart on one component ring, and a pair of hands on the other. When joined, the hands fell over the heart, protecting it from harm.

A ring with a clasped hands design. (Image: Public Domain)

The gimmel ring below, held at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, is a German creation from 1631. One side of the split bezel features a ruby, the other a diamond. When the combined ring is broken apart, you get a diamond ring inscribed with “QUOD DEUS CONIUNXIT” and a ruby ring with the words “HOMO NON SEPARET.” Quod deus coniunxit homo non separet: Whom God has joined together, let no man tear asunder.

The most striking feature of the 1631 ring is its inclusion of a memento mori—a reminder of death amid all the love and unity. A cavity beneath the diamond ring’s bezel holds a tiny, curled up baby, while an identical hollow on the ruby ring is home to a smiling skeleton. Together they are birth and death; beginning and end. Just a reminder that marriage doesn’t make you immortal.

Once a couple had entered matrimony, the conjoined rings were usually worn by the wife. Sometimes, says the 1912 guide Chats on Old Jewellery and Trinkets, one half would ”be given by persons going on a journey to those left behind, to be a kind of token to establish the identity of a messenger.”

This token-of-identity function was also useful in a marriage context. In the notes on a 17th-century gimmel ring, a British Museum curator points out that until England and Wales introduced the 1753 Marriage Act, a marriage didn’t require a formal ceremony to be valid. Mutual consent was enough, and there were “certain signs and symbols that could indicate consent.”

With its dual components, each held by one half of the couple, the gimmel ring was the perfect way to convey that both parties were game for a legally wedded life.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook