The Smugglers Who Hid Booze in the Home of Saudi Arabia’s Top Religious Official

The tale of the most audacious bootlegging ring in Saudi Arabian history.

In Saudi Arabia, Islamic law is sternly enforced—which means, of course, that alcohol is strictly forbidden. But as with any forbidden substance anywhere in the world, that means little behind closed doors, where alcohol flows freely for those willing and able to pay. And like any country (or state) where popular substances are illegal, Saudi Arabia teems with dealers and smugglers profiting from low availability and high demand.

But in a land where even the consumption of alcohol is punishable by prison sentences and the humiliation of public floggings, where do you store your stockpiles of bootlegged liquor away from the prying eyes of the religious and legal authorities?

Why not right under their noses?

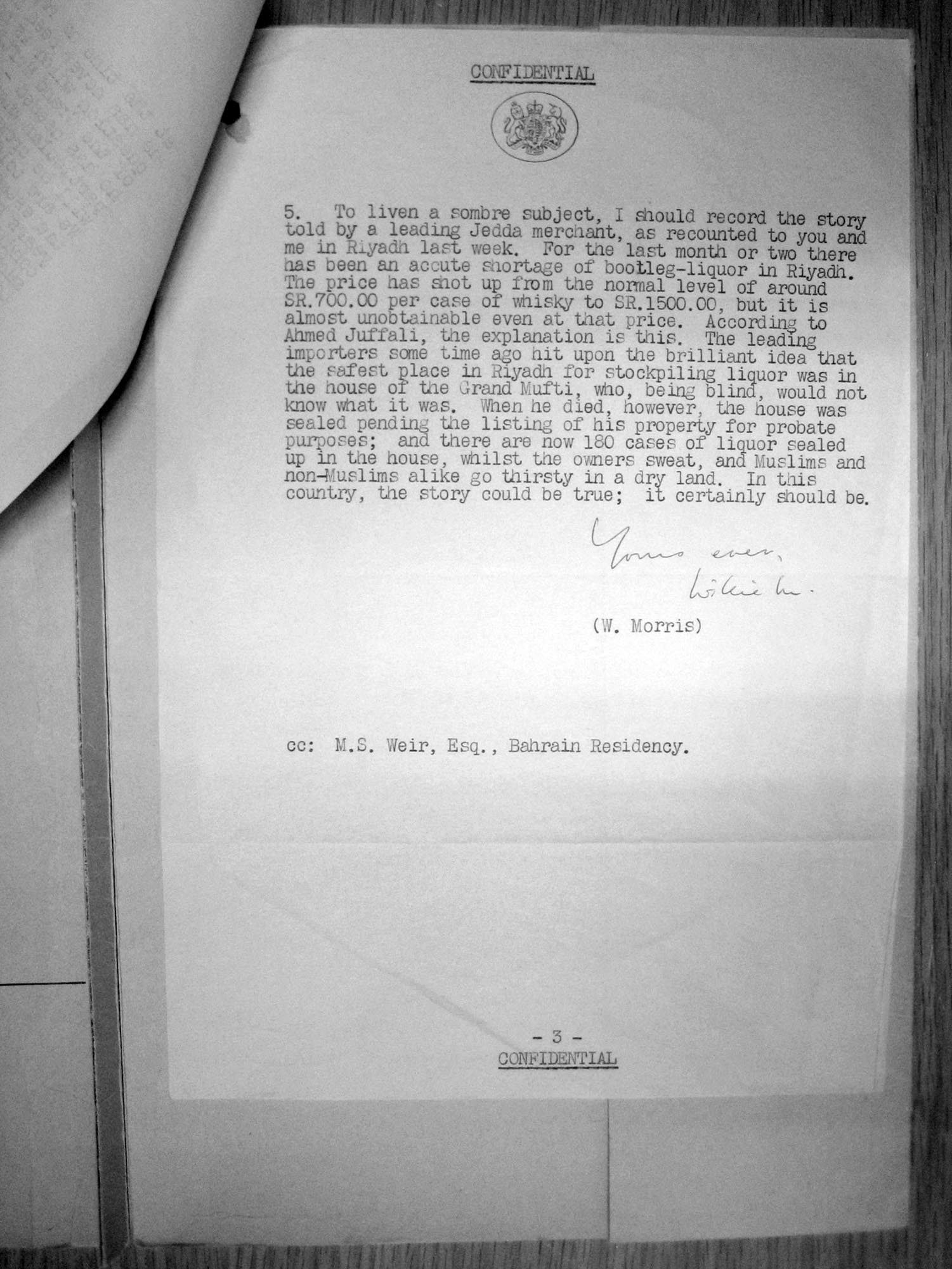

According to a letter sent by Sir Willie Morris, the British Ambassador to Saudi Arabia in 1970, this is exactly what one gang of entrepreneurial alcohol smugglers attempted to do.

Muhammad ibn Ibrahim was the first Grand Mufti of modern Saudi Arabia. This meant he was the state’s highest legal and religious authority tasked with issuing opinions (fatwas) on any and all legal and social issues, including the consumption of alcohol and other banned substances.

A descendent of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab—the 18th-century religious scholar who helped provide the framework for the modern Saudi state—Muhammad ibn Ibrahim was far from a popular man when he died in 1969 at the age of 80, according to Morris’ letter. This was partly due to his conservative religious rulings but also due to rumored abuses of power, which included lobbying the King to lift restrictions on rent so he could make more profit on his “considerable properties.”

“Perhaps he was not so bad as his reputation but he was certainly bigoted, reactionary and mean,” Morris wrote after ibn Ibrahim’s death. “I doubt whether many people here were remembering him in their prayers.”

They weren’t remembering him in their toasts, either. Shortly after the Grand Mufti’s death, Riyadh suffered a severe shortage of bootleg liquor, and—as any casual student of economics could predict—the cost shot through the roof. The price of a case of whiskey reportedly doubled, from 700 Saudi Riyals to 1500 (approximately $400 to $2,500, adjusted for inflation). Even at that price, Morris adds, “it was almost unobtainable.”

The two events were not unrelated. According to a top Jeddah-based merchant cited in Morris’ letter, one gang of alcohol smugglers had been using the Grand Mufti’s home to store their product, reasoning that Muhammad ibn Ibrahim, having gone blind in his old age, wouldn’t know what the boxes contained even if he were to stumble upon them.

And who would think to look for bootlegged alcohol in the home of the most important religious figure in the country anyway, the man responsible for upholding the nation’s Islamic laws and principles?

Their plans hit a wall when ibn Ibrahim died. His house was sealed while the property was listed for the purpose of proving his will and, along with the Grand Mufti’s personal items, 180 cases of liquor were trapped inside “whilst,” Morris wrote, “the owners sweat and Muslims and non-Muslims alike go thirsty in a dry land.”

It’s difficult to confirm any details about this opportunistic group of bootleggers – or if the story was ever anything more than rumors and urban legend. But throughout Saudi Arabia’s modern history, tales have circulated of the different ways people have found to get around the country’s strict anti-drinking laws.

Beginning in 2015, Saudi customs officials began taking to social media to publicize some of the failed, albeit highly creative, attempts of alcohol smugglers. One man was found to have taped 14 bottles of liquor to his legs, hidden beneath his free-flowing thawb (a traditional form of loose, white robe worn by men throughout the Arabian Gulf) in an attempt to smuggle the bottles over the King Fahd Causeway that connects Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.

In another more creative, albeit ultimately failed, attempt, smugglers individually wrapped 48,000 cans of Heineken in fake Pepsi labels to try and pass the beer off as harmless soft drinks. They were foiled by shoddy workmanship (the labels easily peeled) and an eye for detail among the customs officials.

ملصقات “مشروب بيبسي” على 48 ألف علبة بيرة بالكحول كشف محاولة تهريبها جمرك البطحاءhttps://t.co/BwpTaeQs1n pic.twitter.com/gpf9p7ZK1Z

— الجمارك السعودية (@KsaCustoms) November 11, 2015

From the twitter account of Saudi Arabia’s customs department, an attempt to smuggle in beer by disguising it as Pepsi.

جمرك جسر الملك فهد يُحبط محاولة تهريب كمية من الخمور مخبأة أسفل الثوب الذي يرتديه المهربhttps://t.co/9clje1YiRM pic.twitter.com/D0XDKbMTnm

— الجمارك السعودية (@KsaCustoms) January 24, 2016

An attempt to smuggle Johnny Walker Red Label.

Due to the high risk involved and the difficulty of moving product in high numbers, name-brand liquor comes at a cost. One diplomatic cable from 2009 released by Wikileaks put the price of a black-market bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label at $800 due to a shortage in supply. (In the United States, the whiskey would cost from $40 to $50). It’s no wonder many in the country resort to brewing their own.

As in Prohibition-era United States, this has led to the rise of modern-day speakeasies—especially behind the walls of the expatriate enclaves, where authorities mostly turn a blind-eye to illicit activity. Unlike the Prohibition-era U.S., though, which brings to mind celebrity mafiosi and blood-drenched streets, there is little evidence of high-level gangsters in Saudi Arabia operating complex networks of suppliers, smugglers, and dealers, infiltrating the police and border agency at their highest levels, or settling business differences with irrefusable offers.

At the turn of the millennium, however, things did turn briefly violent between rival factions of Saudi alcohol providers, at least according to some.

Four bombings carried out over three months in the country were linked to expatriates who, according to Saudi authorities, used radio-controlled bombs to target the cars of their competition. One British man, Christopher Rodway, died and five others were injured in the attacks. Five British expatriates, a Canadian, and a Belgian were deemed responsible and confessed to the crimes on national television. Abel al-Jubeir, the foreign affairs adviser to the Crown Prince, claimed the attackers and victims were members of “rival gangs who were involved in smuggling alcohol,” who had turned to violence to settle scores.

The accused deny the charges and have since been released. Many observers believe they were forced to confess to hide the reality: that the bombings were carried out by anti-Western extremists who were opposed to Saudi ties to the U.K. and U.S.

As for the gang behind the Grand Mufti’s stash, nobody can be sure what happened to them or their stockpile. Muhammad ibn Ibrahim’s family continues to occupy the most important religious and legal seat in the country and smugglers and bootleggers are finding new ways to to quench the thirst of the Saudi desert, each more ingenious than the last. But with the exception of the rum-runners and authorities involved, it’s hard to know if this particular tale is anything more than an urban legend.

Still, as Morris wrote: “In this country, the story could be true; it certainly should be.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook