The Socialite Who Stopped at Nothing to Hunt Down Ancient Music

A photograph from 1935 of a dance orchestra in Point Barrow, Alaska, with drumheads made from whale stomachs. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Depending on who you ask, Laura Boulton was either a pioneering ethnomusicologist who made a substantial contribution to her field in the middle of the 20th century by recording hundreds of hours of songs from cultures around the world, or she was something of a tomb raider who “collected” and profited off of tribal cultural property.

Getting to the bottom of Boulton’s legacy is something that matters a lot to Aaron Fox. As Director of the Columbia University Center for Ethnomusicology, and curator of Boulton’s collection, Fox has been leading the effort to repatriate the songs that Boulton recorded, which have been owned by the Library at Columbia University since the early 1960s, back to the communities where they were originally created.

However, the recordings have a complex ownership history, making the mystery of Boulton’s legacy as difficult to decipher as the question of who these songs belong to, and where they should be kept. “How you view Laura Boulton is in some ways the Rubiks cube for how you view who has the rights to own these recordings,” says Fox, who is usually wearing cowboy boots and jeans, an atypical look for an East Coast academic.

“You could see her as she would have liked to have been remembered, a music hunter, or a song catcher, who was nobly documenting and collecting on behalf of science. Or you could see her as 20th century trope, a Dale Carnegie type, an uncompromising self-promoter and huckster who went into villages and said, ‘Bring me the singers!’ and, ‘Let’s wow the natives with our modern technology!’ And then made a living selling her exotic stories on the lecture circuit.”

Boulton was born in 1899 to a middle-class family in Conneaut, Ohio, and later went on to study music at Denison University. But her musical adventure began in earnest when she married Rudyard Boulton, an ornithologist and lecturer at the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, who was doing fieldwork thousands of miles away in Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, and what was formerly Tanganyika, under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History.

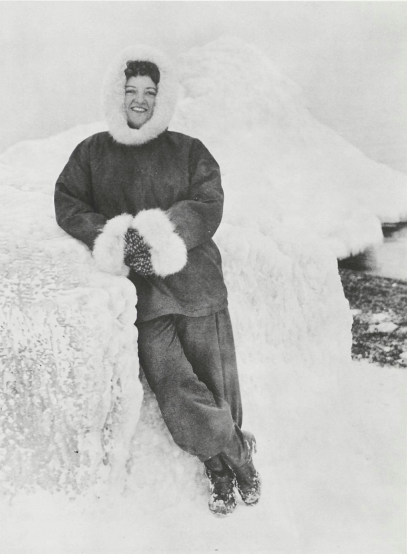

Laura Boulton on a trip to the Arctic. (Photo: Columbia Library Columns Journal)

Laura Boulton on a trip to the Arctic. (Photo: Columbia Library Columns Journal)

A kind of self-styled Teddy Roosevelt, Rudyard gave his socialite wife a cylinder recorder to occupy her time during a three-month trip they made in 1929. While he was off collecting artifacts, photographing birds, and hunting big game, she ventured into a mountain rainforest camp, and made her first recordings. From that moment on, she was hooked.

Boulton spent the next 30 years conducting musical expeditions in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Arctic and America, where she describes her mission as nothing short of total: “To capture, absorb, and bring back the world‘s music; not the music of the concert hall or the opera house, but the music of the people…” she writes in her autobiography, Music Hunter.

A prolific writer and keeper of notes, she also amassed descriptions of her travels and observations, including accounts of “personal gun-boys” in Africa, introducing Mbundu elders in Angola to Bach, and riding the Eastern Arctic seas on her way to encounter the “Eskimo,” whose songs she called “the most primitive in her collection,” and therefore “unusually interesting.” She casts her subjects as shy, exotic people, who had never before seen recording machines, and lived in a distant past.

By the 1960s, Boulton had collected some 30,000 recordings from the Northwest Coast, the Southwestern United States, and Mexico, as well as Afro-American, European folk, Byzantine, Orthodox, and Ethiopian liturgical music. She eventually sold a portion of this collection to Columbia University, where it became the bedrock of its PhD program in ethnomusicology.

For years, this collection also stood as a monument to Boulton’s achievements—not many women in her day were able to travel as widely as she did, nor contribute so much to musical scholarship—and to a certain way of thinking about culture. Rooted in 19th-century German social thought, it was a way that saw cultural difference in biological terms. If her writings are any indication, Boulton believed she was salvaging cultures and races that were vanishing because they were not evolved enough to survive in the modern world.

It is precisely this legacy that Fox, and the Columbia University Center for Ethnomusicology, are attempting to unravel. Using an approach called community-partnered repatriation, they are returning some of these songs to their original communities. And even though the publication rights of the recordings continue to be legally owned by Columbia, it’s giving the descendants the power to decide how the rights should be assigned, where the recordings should be kept, and how they should be preserved.

Most repatriation projects ignite bitter debates because they threaten to undermine an institution’s holdings, or cast its past in an ugly, racist light. But to Fox’s mind, this co-curatorial approach is the best way to transform Boulton’s collection into an ethical scholarly resource, one that is researched and informed by the people who created and performed the songs in the first place.

“It is not the point to say Laura Boulton ‘stole’ anything, although that is one valid interpretation,” Fox says. “The point is to question the entire relationship between music scholarship and the academy more generally with the oppression and genocide of indigenous peoples.”

So far, the project has focused largely on Native American and Alaska Native communities, leading Fox and his various research partners back to the Inupiat community, in Barrow, Alaska, where Boulton first encountered the “Eskimo” songs in 1946, and to the Hopi in Arizona.

“We find when we talk in the abstract, ‘We have this intellectual property and we want to bring it back,’ people say, ‘Oh yeah, this is our cultural property, we will take it, and then it just sits on the shelf,’” says Trevor Reed, a member of the Hopi tribe who is directing the Hopi project for Fox in preparation for a related law degree. “So much elder knowledge has been lost, but there’s something about being in the presence of these voices that makes people think, ‘Wait we could utilize these songs in ways that would help people remember these practices, ceremonies, ideas, and different language components.”

Not surprisingly, there is also plenty of evidence that the people that Boulton recorded were not nearly as primitive as she thought. In his blog, Reed describes how some tribal members took Boulton for a fool, as when Hopi leaders performed Zuni songs and dances for her, knowing that she, a white lady from Ohio, wouldn’t know the difference.

“Most informants were smart enough not to sing the sacred songs to white people,” Fox says. “So the entire premise that Boulton was working under, that she was salvaging disappearing, primitive cultures, was entirely wrong. It also refused to recognize the modern political agency of indigenous people.”

As Fox was saying this, he was driving through Arkansas on his way back from Oklahoma, where he had met with elders from the Ponca tribe about repatriating a batch of powwow songs that were performed as part of the sacramental taking of peyote in the Native American Church.

He hopes that such efforts can build on the sovereignty movement of the 1950s and 1960s, when tribal activists began insisting on recovering the cultural patrimony that had been stolen from them.

“Why do you think Trevor Reed is going to law school?” Fox asks. “Because the next generation of indigenous activists are going to do with music what the last generation did with human remains.” He adds, “The most important facts about these recordings is that, in most cases, the songs are not lost.”

This is part of a bimonthly series about early female explorers. Previous installments can be found here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook