America’s First Ramadan Break-Fast Was Hosted by Thomas Jefferson

The United States’ first iftar took place at the home of the third President.

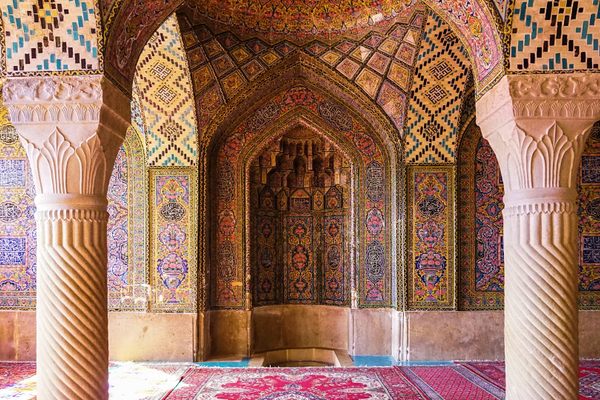

In 1805, the month of Ramadan fell in December. Far from his friends, family and home, one Tunisian man was attempting to observe it in Washington, D.C. This was the statesman Sidi Soliman Mellimelli, who was spending six months in the United States, on a diplomatic mission.

Observing this holy month and its daily fasts in such a foreign environment must have been a challenge. Newspaper commentators at the time thought of him contemptuously, variously “depicting him as a sex-crazed barbarian, or associating Islam with licentiousness,” writes Jason Zeledon. But in Thomas Jefferson, he had an unexpected ally. Despite facing criticism for his hospitality from Federalists in Connecticut and Vermont, Jefferson looked after his Muslim visitor graciously, going so far as to rearrange a dinner party around Mellimelli’s fast. In doing so, America’s third president became the country’s first ever host of an iftar meal.

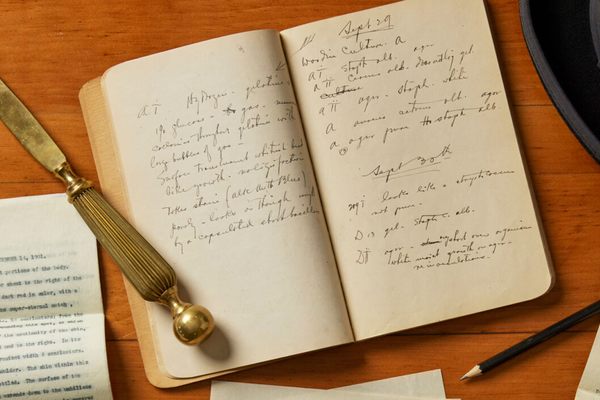

On December 7, Jefferson’s secretary visited Mellimelli to invite him to a 3:30 p.m. dinner with the President. When he arrived, Mellimelli was praying on his mat. “Rising from the ground, he addressed the Secretary in the same manner as if he had just come in from another room,” senator William Plumer reported. “He replied he could not eat this month until after sunset.”

That could very easily have been that. Instead, Jefferson postponed the meal by around 90 minutes to “precisely at sunset.” (Modern calculations suggest this was likely just before 5 p.m.) John Quincy Adams, who also attended the dinner, noted that this move was due to “it being in the midst of Ramadan, during which the Turks fast when the sun is above the horizon.”

That night, Mellimelli was a little late—he may have decided to say his evening prayers at home, before attending the dinner—but sat down and broke his fast with them. They smoked together, shared copious dishes, and talked through Mellimelli’s interpreter.

It was, by no stretch, a traditional iftar, nor what Mellimelli would have been used to, without sweet dates to start the meal or the Tunisian dishes he was familiar with. But this gesture of hospitality must have seemed an outstretched hand at what was perhaps a very lonely time—a recognition that Jefferson and his peers respected and valued Mellimelli’s religious practice, and would do whatever they could to accommodate him, and it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook