For Sale: Sir Thomas More’s Utopian Alphabet

The humanist scholar fudged a language into existence.

There’s a rhyme and reason to most made-up languages. Tenses and conjugations, turns of phrase and various voices—sometimes constructed languages, or conlangs, are even more complicated than long-extant lingos. Yet others, even when made to represent lofty ideas, are quite crude, with language rules akin to Pig Latin.

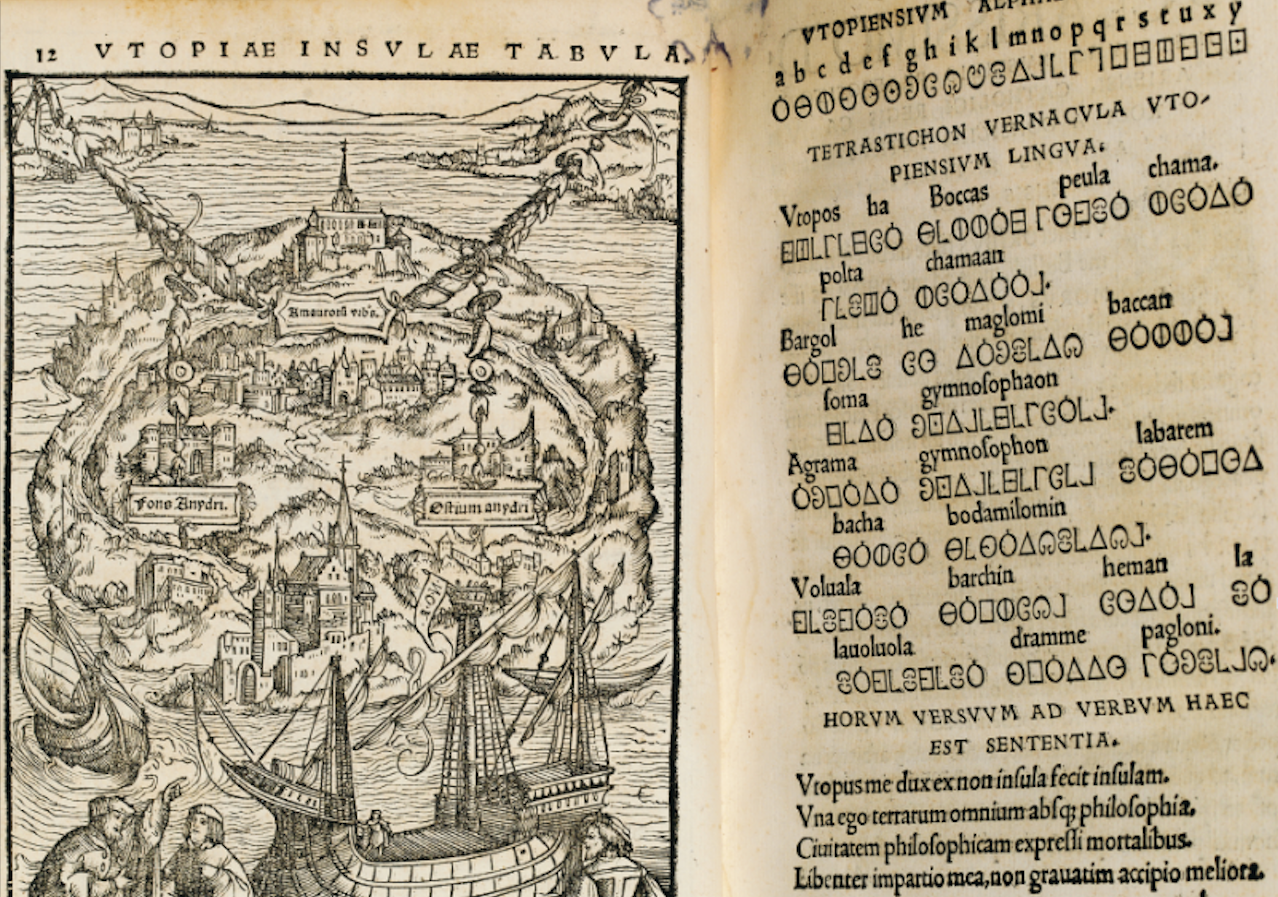

That was the case for a language invented by the 16th-century Englishman Sir Thomas More, who satirically envisioned an ideal nation with an insufficient knowledge of linguistics. More printed a map of his fictitious “perfect world,” with a quatrain in “Utopian,” in some early editions of his landmark work of fiction from 1516, Utopia.

Now a rare 1518 copy of the book, including the illusory world’s conlang, is for sale and will be presented this week among other very old books at New York City’s International Antiquarian Book Fair.

“[Utopia] is an example of that rare thing—a book that has never been out of print since its first publication,” writes Derek McDonnell, founding director of the Sydney-based bookshop Hordern House, via email. “This is the third edition of the text, but the most important of the early editions, as it has the beautiful illustrations and decorations by the two Holbeins [the German painters Ambrosius Holbein and Hans Holbein the Younger].”

Like the satirically perfect nation-state More imagined, the book Utopia was deeply flawed in the eyes of its author, and went through many different editions, sometimes excluding older bits while incorporating new information.

The work wasn’t entirely More’s, as his friend and publisher Desiderius Erasmus added some of his own musings. The unique Utopian alphabet, printed opposite a map of the made-up world, was either the brainchild of More himself or of his friend Pieter Gillis, another humanist printer, who claimed to be responsible for the cryptic language’s inclusion.

Nor was it the first conlang. That distinction goes to the Lingua Ignota, or “unknown language,” of the famous 12th-century polymath Hildegard of Bingen. But while Hildegard used her script in real life, More’s Utopian was intended only to introduce readers (it appears at the front of the book) to an alien place where religious tolerance and universal education were par for the course. Imagine that.

The characters in the Utopian language walk the line between Greek and geometric runes. There is no casing, just large circles, squares, triangles and lines, with various accents attached. It would be gobbledygook if not for its accompanying Latin translation, which speaks to the creation of Utopia and its singularity as a philosophical—and aspirational—place.

“The alphabet reflects a general humanist preoccupation with classical Greek culture,” says Per Sivefors, a literary scholar at Linnaeus University in Sweden who specializes in early modern writing. “A word like gymnosophaon is clearly made up to sound Greek.”

“Beyond that,” he says, “I believe More and his humanist circle enjoyed using the available technology to explore a fundamental paradox at the heart of the work. The very title of course means ‘nowhere’ [More coined the word “utopia” from the Greek outopos], yet at the same time, the various visual devices, including … the woodcut maps that were in the editions of 1516 and 1518, somehow compel us to see this as a ‘real’ place populated by real people with a real language.”

Perhaps that’s what makes the land of Utopia so compelling: We know a lot about its geography. The island was located off the coast of South America, More writes, and shaped like a crescent moon about 500 miles around. Like Atlantis or Jurassic Park, the more it feels like a real place—complete with tangible cultural artifacts like a map and a language—the more achievable it seems.

Perhaps More could’ve done with a more Utopian setting himself. His life ended, after all, at the sharp end of an executioner’s axe, after the senior statesman refused to endorse King Henry VIII’s divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Perhaps the rarest edition of Utopia (only six are known), the classic for sale here will boast a price tag of $81,000. A hefty sum for some, but a small price to pay, some would say, for an early musing on what the world could be.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook