How the Real Madame Tussaud Built a Business Out of Beheadings

Marie Grosholtz sure loved to make death masks of freshly executed criminals.

Few people knew the unapologetic sensationalism of Victorian popular culture better than Marie Grosholtz, better known as Madame Tussaud of wax-museum fame. Born to a family line dotted with public executioners, and apprenticed to her mother’s employer, an anatomist who sculpted in wax, Marie was not exactly the sort of girl who dreamed of white lace and piano lessons: instead, she honed her skills making death masks from guillotined heads during the French Revolution.

Marie was born in 1761. Her mother, a widow, was housekeeper to the famous waxmaker and anatomist Philippe Curtius, who all but adopted Marie (rumors abounded: was Curtius her uncle, her father, or a convenient cover for parentage by some unknown noble?). Curtius considered the girl a prize pupil, and in his wax salon, Marie encountered many of Paris’ prominent citizens. Her first sculpture was a likeness of Voltaire.

In the 18th century waxworks became popular as a public, paid attraction; and women—including London’s famous Mrs. Salmon, and Patience Wright in Philadelphia—were surprisingly prominent in the trade. Perhaps this was because wax was seen as a “lesser” medium for sculpting, or because male academics and artists satisfied themselves it was an amateur pursuit; but whatever the reason, Marie ran with it, bringing along her artistry, an iron stomach, social savvy and a liberal definition of educational entertainment.

The French Revolution created a new demand for wax figures. As Pamela Pilbeam details in her book Madame Tussaud and the History of Waxworks, the sculptures—typically wax heads mounted on costumed mannequin bodies—became a sort of real-time political commentary for Parisians in salons like those Curtius operated. And while Curtius was out participating in the city’s political and military life, it often fell to Marie to make death masks of the Revolution’s recently decapitated victims.

The work required equal comfort in palaces and in prisons, and a certain ease with the grotesque: in her memoirs, Tussaud claimed that she sat “on the steps of the exhibition, with the bloody heads on her knees, taking the impressions of their features.”

Success in waxworks involved not only artistic skill and patience, but an ear to the ground and fast feet: when Charlotte Corday murdered the radical Jean-Paul Marat in his bathtub, Marie got to the scene so fast, the killer was still being processed by law enforcement as she started work on Marat’s death mask.

In 1802, 40-year-old Marie was saddled with a lazy, spendthrift husband, two children and the faltering business Curtius had left her on his death, and she decided to seek her fortune abroad. She left her youngest child with her mother and aunt, packed up her four-year-old son and a duffel bag of disembodied aristocratic wax heads, and left for England to achieve a “well-filled purse,” according to Kate Berridge in Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax.

Marie wanted to provide for her sons; she knew that her spendthrift husband would get any money she had if she returned to France; and the Napoleonic Wars made it difficult for her to travel anyhow. So she doubled down on her hustle: Marie found her footing, bought out her contract with Paul Philipstal, a Curtius colleague with whom she had tentatively partnered on arrival in England, and toured for more than 20 years throughout England and Scotland, establishing her traveling show as a cultural fixture. She was known to seize quickly upon every trend and fashion, making new models to explore what Pilbeam called “the snobbish glamour of royalty as well as the thrill of being au fait with the latest gruesome murder or assassination.” Moreover, she had authenticity on her side: anyone could make a diorama, but only Marie Tussaud could claim she had taken her casts from the very individuals portrayed.

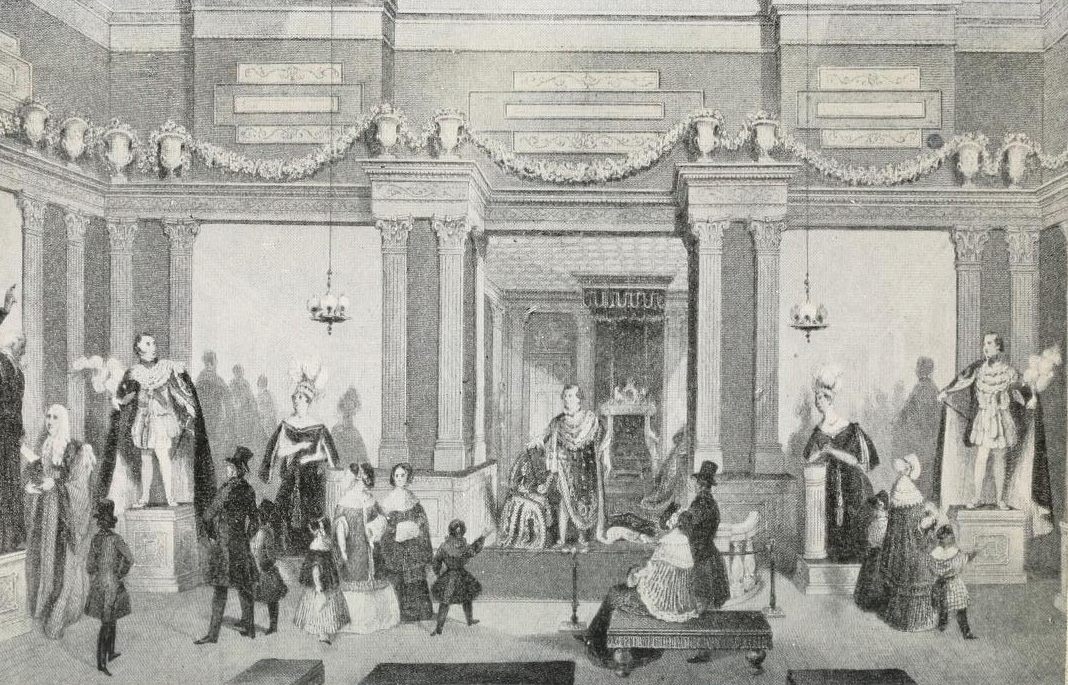

As she got older Marie capitalized on the chance to rein in her travel and tap into the growing “promenade market” of families with discretionary income. She settled into a standing location in London’s fashionable Baker Street in the middle 1830s, when she was 74 and still greeting guests personally. Tussaud’s Baker Street gallery featured a 5,000-square-foot grand salon, covered in ornate drapery and offering comfortable seating where visitors could take in the sculpture (helpfully flattered by large mirrors on the walls, generously reflecting the figures from every angle).

Madame Marie knew that the public, then as now, would go nuts for two things—royal fever and horror shows—and she gladly provided immersion in both. Insinuating herself with the upper class, Tussaud grew her popularity to the point where she was able not only to model Europe’s elite, but to purchase King George IV’s coronation robes and Napoleon’s own carriage, all the better to ornament displays in the “Golden Chamber.” In the early 1840s, Tussaud put together a royal display with Albert sliding the wedding ring onto Queen Victoria’s finger; and commissioned (with the Queen’s permission) a precise copy of her wedding gown, at a cost of a thousand pounds.

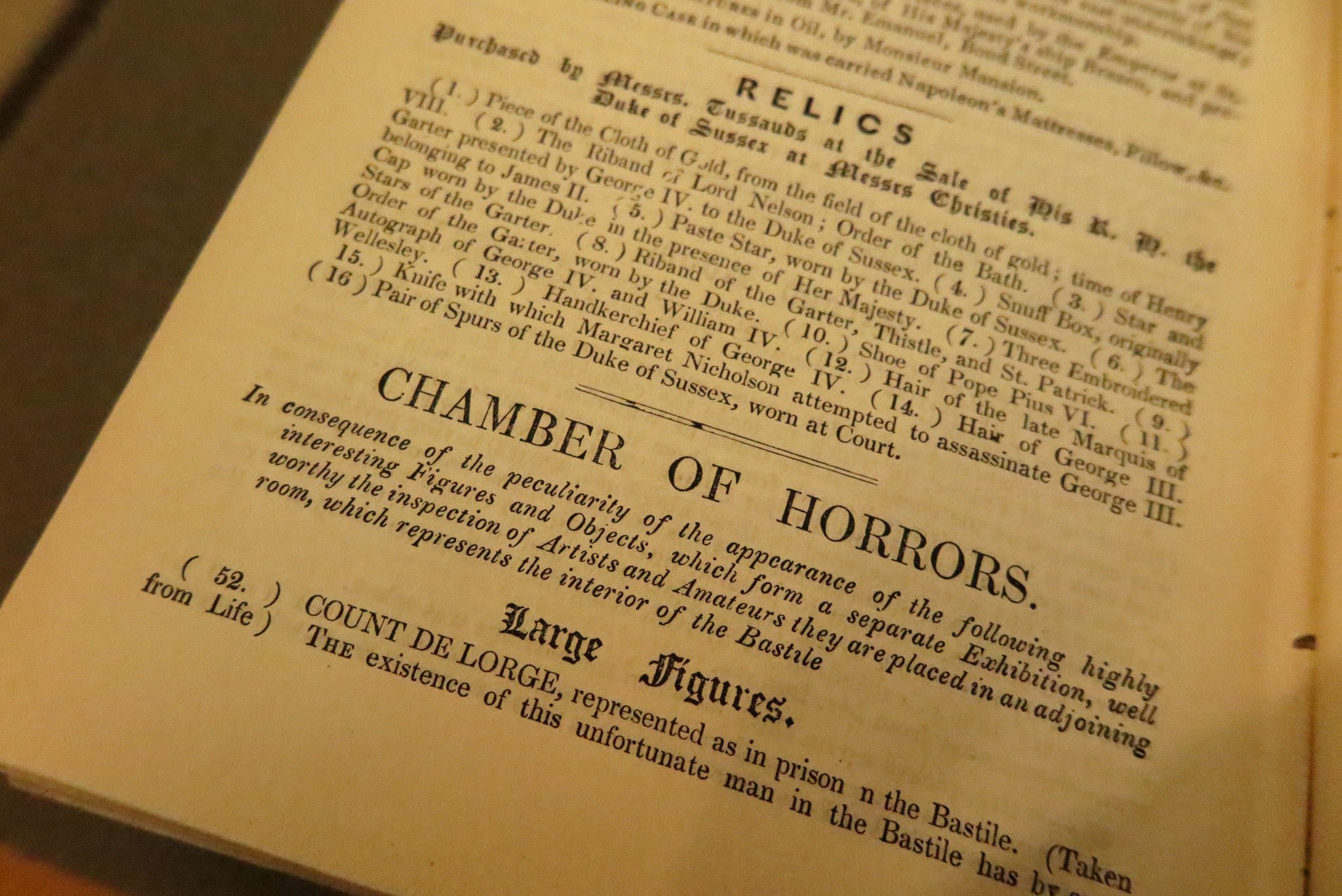

The “Chamber of Horrors,” often euphemistically referred to as the “Adjoining” or “Other” room for decorum’s sake, featured grisly recreations of murder scenes so infamous that criminals headed for execution would sometimes donate their own clothing to the gallery in the interest of veracity.

The Chamber of Horrors paid tribute to the Revolution with a working scale-model guillotine, and the heads of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and Robespierre—the latter grimly squashed in, to reflect the botched suicide attempt in which Robespierre allegedly shot off half of his own jaw. (A catalog of the gallery helpfully distinguishes “large figures” from “heads.”)

Famous figures in the forbidding salon included an array of British murderers cast from life at their trials, among them James Rush, executed for the triple murder of his landlord and family; and Maria and George Manning, a couple arrested and executed before 50,000 people for the 1849 killing of Maria’s lover.

The body-snatchers William Burke and William Hare were a popular tableau: when a lodger in Hare’s house died, the men decided to sell his body to willing Edinburgh surgeons faced with a cadaver shortage. It worked out so well (and, unlike grave-robbing, no sweaty digging involved) that Burke and Hare killed 16 more people to repeat the transaction, bringing them in sacks to the hospital for no-questions-asked sale. Marie cast Burke’s head three hours after his execution in 1829. Hare turned King’s evidence and escaped the gallows, but was modeled from life by Tussaud’s sons, who had by that time joined her in business.

Presiding over a gallery full of wax royals, dead revolutionaries, and serial murderers, Marie would brook no criticism, instead proclaiming what a public service she was offering:

“Madame Tussaud, in offering this little Work to the Public, has endeavoured to blend utility and amusement. The following pages contain a general outline of the history of each character represented in the exhibition; which will not only increase the pleasure to be derived from a mere view of the figures, but will also convey to the minds of young persons much biographical knowledge—a branch of education universally allowed to be of the highest importance.”

Marie Tussaud was a hustler, and did her part, as her contemporary P.T. Barnum did in the U.S., to create what we recognize as the modern concept of celebrity—renown not being something you achieve after death with a sober legacy, but something you cultivate in life by slaking the public thirst. She died in 1850 with credit for England’s most popular tourist attraction, and even the usually grumpy satirical magazine Punch had to admit: “In these days no one can be considered properly popular unless he is admitted into the company of Madame Tussaud’s celebrities in Baker Street. The only way in which a powerful and lasting impression can be made on the public mind is through the medium of wax.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook