In 1914, Feminists Fought for the Right to Forget Childbirth

They had associations and rallies advocating for “twilight sleep.”

When Charlotte Carmody went to speak about twilight sleep, she brought her “painless baby” with her. In churches and in department stores across the United States, in front of crowds of women who had been rallied by the Twilight Sleep Association, she told her story.

After reading a 1914 magazine article about the possibility of painless childbirth, Carmody had made a pilgrimage across the Atlantic Ocean, to a clinic in Freiburg, Germany, for her own delivery. When she went into labor, the German doctors gave her a combination of drugs; the next moment she remembered was waking up more than 12 hours later.

“Perhaps the baby will come tomorrow,” she thought to herself. It was only after a moment that she realized: “I felt lighter, and sat up easily, and my figure had changed.”

Minutes later, a nurse handed over her son. She named him Charlemagne, although at first she didn’t believe he was hers: She didn’t remember his birth. “The twilight sleep” had swallowed the experience up and blanked it from her mind.

In later years, twilight sleep, in which women were put into a drug-induced trance, would come to exemplify America’s “knock ‘em out, drag ‘em out” era of childbirth, when women were given little choice about being medicated into a stupor during labor. But in 1914 and 1915, twilight sleep was a cause célèbre among American feminists, who formed twilight sleep associations and tried to spread the gospel. Like today’s home-birth movement, the movement promoting twilight sleep called for women to take control of their birth experiences and speak up against doctors who would deny them this choice.

Carmody, an early adopter of twilight sleep, was one of its fiercest advocates. “If you women want twilight sleep you will have to fight for it,” she told women rallying for the cause, “for the mass of doctors are opposed to it.”

But while the feminists running the twilight sleep movement were trying to gain control of their bodies, the method they advocated was turned against them and used to rob laboring women of agency.

The push for twilight sleep started with a McClure’s Magazine article published in June 1914 by Marguerite Tracy and Constance Leupp, who had traveled to Freiburg and come back with glowing reviews of “a new and painless method of childbirth.” This method was safe and successful, they reported, and women from all over the world—from India, Russia, South Africa, and North and South America—were coming to the “odd old town” to experience twilight sleep. One person who had delivered a baby at the clinic declared “she would never again have the blessing of a baby without the attendant blessing of the Twilight Sleep,” the journalists wrote.

Tracy and Leupp described twilight sleep as “a very fine balance in the states of consciousness,” which required “special knowledge of the use of drugs that cause it.” Once a woman had gone into labor, she was given a combination of morphine to dull the pain and scopolamine to dull her memory of the experience. (Today, scopolamine is sometimes called the “zombie drug” because its users become susceptible to suggestion but retain no memory of their actions.)

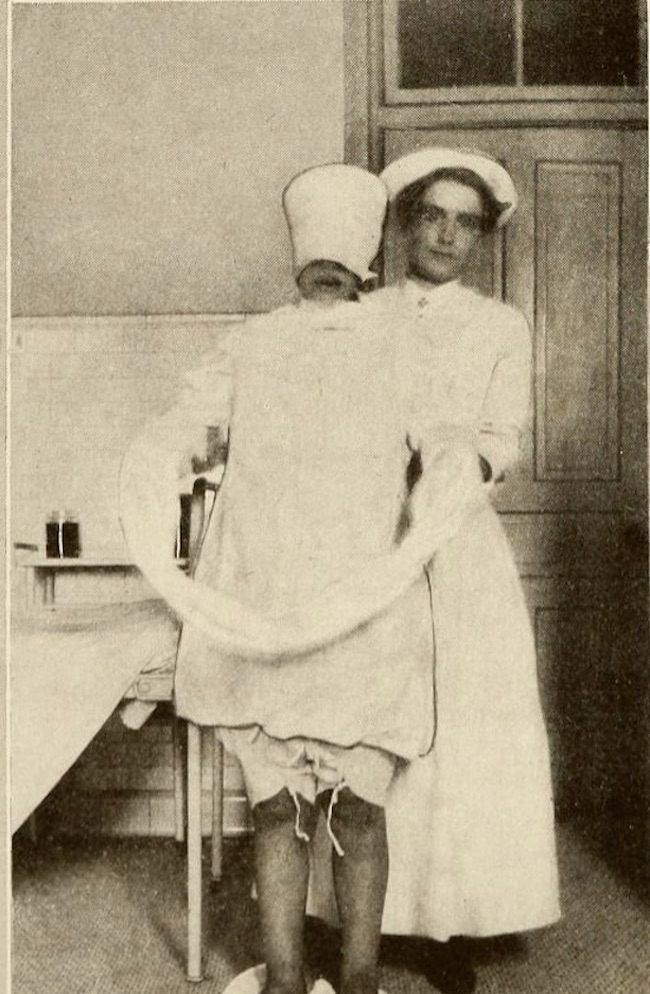

These drugs had been used in the past as anesthetics, but few doctors had adopted them with enthusiasm. But the German clinic, the McClure’s article reported, had reached a technical breakthrough with scopolamine, which allowed the doctors to administer it with more precision and therefore with more success. Women who they treated with these drugs would retain muscle control and would follow orders from doctors, but would remember none of it.

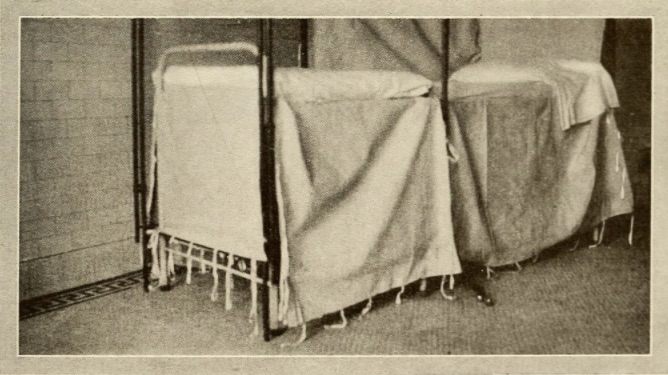

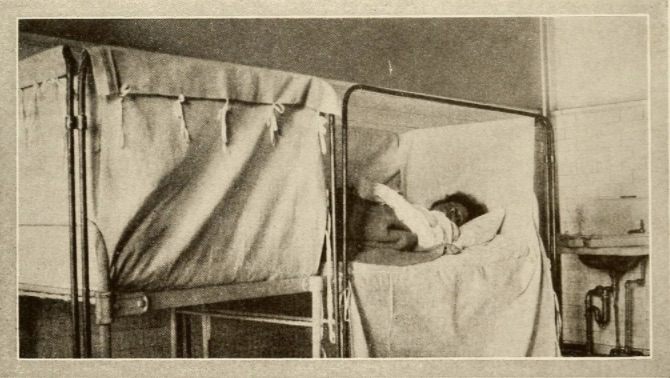

There were some strange conditions that went along with the use of these drugs. Because the women’s state of suspension was precarious, women in twilight sleep were kept in padded, crib-like beds, with eye masks blocking out the light and cotton balls in their ears blocking out sound. Sometimes they were fitted into straight-jacket-like shirts that limited the movement of their arms. When the birth was over, women also often experienced a moment of dissociation, as Carmody did: Had they really had a baby? Was the baby they’d been handed really theirs?

But to Tracy and Leupp, the benefits of this method were obvious. At the time, there was a growing concern, roughly analogous to today’s worry about the overuse of C-sections, that doctors were too quick to use forceps, which could increase risk and prolong women’s recovery time. The Freiburg clinic rarely used forceps in deliveries. The clearest selling point to the journalists, though, was women’s experience: They awoke from Twilight Sleep without a memory of the pain of childbirth and were soon out of bed, getting to know their new child.

Carmody was the first woman to travel to Freiburg to give birth after the McClure’s article was published, and she came back with glowing reviews. But she barely beat the rush of American women to Freiburg. Tracy and Leupp’s article, McClure’s later reported, had attracted more attention than any other the magazine had ever published.

Advocates of twilight sleep didn’t want American women to have to travel to Germany to obtain this treatment, though. They started demanding that doctors and hospitals in America give women this option, and they formed the National Twilight Sleep Association to further their cause.

Led by Mrs. C. Temple Emmet, a member of the wealthy Astor family and the first American ever to have a baby at Freiburg, the association quickly formed plans for expansion by sending lecturers around the country and organizing branch associations. Not all of its leaders were from the wealthiest ranks of Americans; the association’s board included an elementary school teacher, a dental nurse, and the wife of a miner. At Twilight Sleep Talks women would extol the virtues of “painless childbirth.”

“I was so happy,” one women declared. “The night of my confinement will always be a night dropped out of my life,” says another. The association celebrated when a “tenement house mother” gave a twilight sleep speech on the corner of her street.

The twilight sleep movement was immediately controversial, though. While feminist women pushed for access to the technique, doctors fought back. They “refused to be ‘stampeded by these misguided ladies,’” historian Judith Walzer Leavitt wrote, in her account of the movement. Doctors wrote in the popular and academic press about the dangers of twilight sleep and argued that one popular article shouldn’t guide medical practice. But the practice also had advocates in the medical community, and soon American doctors were also traveling to Freiburg to train in twilight sleep techniques.

But, as innovators today might say, twilight sleep didn’t scale well. Even in the original McClure’s article, Tracy and Leupp wrote that the Freiburg method was almost impossible to practice in large hospitals, where space and the attention of doctors was at a premium. As twilight sleep was practiced at Freiburg, a woman ideally had her own room, to minimize the chance she’d be disoriented, and the doctor paid close attention to her progress through the whole course of her labor. At Freiburg, the clinic was only able to accomplish this level of care by tripling their delivery room staff, thanks to the support of the Grand Duke of Baden. When doctors and hospitals in America started adopting this technique, they usually were not able devote that same attention to individual women, and the outcomes suffered.

There was also a gruesome aspect to twilight sleep. Although women did not remember having pain during childbirth, they were still experiencing pain. That’s part of the reason their beds were padded and the women’s arms constrained—they would writhe and yell during labor. The doctors at the time understood this: “There is as much [pain] as in the ordinary childbirth,” one doctor told The New York Times. “The only difference is that the patient does not remember having the sensation of pain.”

Women who took the drugs did sometimes have memories of their labor and the attendant agony. One twilight sleep patient remembered telling the doctor, “I am having a very bad pain.”

“You are having a very bad pain,” he replied. In her memory, the experience was impersonal and far away. But for non-drugged observers, seeing the women’s pain could be horrific. One twilight sleep hospital on Riverside Drive was almost shut down by noise complaints from neighbors, who could hear the laboring women screaming.

For the women who advocated for twilight sleep, though, blacking this out of their memory was considered desirable. “It was an attempt to gain control over the birthing process,” wrote Leavitt, the historian. “Because many of the twilight sleep leaders were active feminists, they spoke in the idiom of the women’s movement.” While to later generations, twilight sleep was a horrifying treatment, in which zombified women were divorced from the experience of giving birth, to this generation, it was a new form of freedom, a way to erase the work and potential trauma of labor.

The twilight sleep movement was short-lived. The McClure’s article was published just before the start of World War I, and soon German technology and ideas were viewed with suspicion. More devastating, though, was the death of Charlotte Carmody, in 1915, while giving birth to her next child, in a hospital in Brooklyn that had adopted twilight sleep. She died of a hemorrhage, and her husband and doctor were both clear that twilight sleep techniques were not to blame. But her death cast a pall on the movement; her own neighbor started an Anti-Twilight Sleep Association. The department store rallies stopped, and the associations soon disbanded.

Twilight sleep, though, stuck around in its own zombified form. Doctors found it convenient to drug women and restrict access to the delivery room, and for decades women were given little choice about whether they’d be knocked out during labor. Scopolamine remained in use until the 1960s, when a new round of journalism about the practice exposed its more gruesome side, including the burns women would have on their wrists from being tied down. What had started as a dream for women, in which the pain of childbirth was wiped away upon waking, had become a nightmare.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook