Why We Couldn’t Describe a Flavor We Taste Every Day

The human tongue detected it long before it could say it.

What if suddenly there were five cardinal directions, Snow White had the company of eight dwarves, or there were thirteen months in the year? What if a number that seemed eternally fixed became augmented by a quality or quantity that had been hiding in plain sight all along?

Sweet, bitter, salty, sour—and umami

Something like that happened in the culinary sciences not too long ago. For most of history, humans knew and named no more than four taste qualities: sweet, bitter, salty, and sour. But the human tongue distinguishes a fifth one, which remained unknown and unnamed until Kikunae Ikeda, a chemistry professor at the Imperial University of Tokyo, identified it in 1908.

Ikeda was intrigued by the dominant taste of dashi, a Japanese soup stock, which according to him was unlike any of the four basic tastes. He took the stock’s main ingredient, a seaweed named Laminaria japonica, managed to isolate its principal taste substance, and named it “umami” (from umai, “delicious” in Japanese).

So, what does umami taste like? It has been described as meaty and savory, but it’s a complex and subtle taste, even in high concentrations. In fact, umami is more of a helper flavor, enhancing the saltiness or sweetness of other foods, which explains why it has remained under the radar for so long.

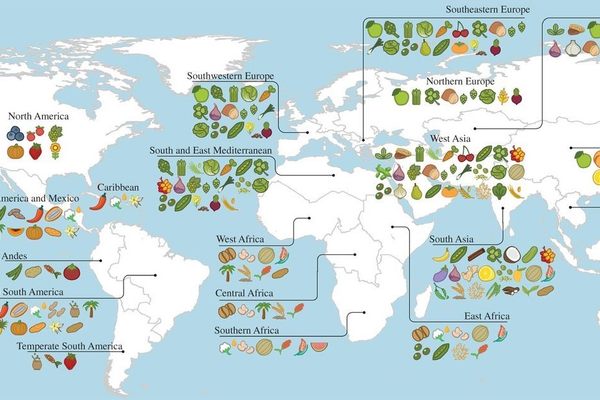

Umami comes from molecules found in meat (inosinate), plants (guanylate), or both (free glutamate). Some processes like aging and fermenting create free glutamate, bringing out the umami flavor. (Think: cured meats or cheeses.) But umami is also strongly present in mushrooms, seafood, and tomatoes. The latter points to why ketchup is such a popular condiment: its umami-ness acts as a flavor enhancer.

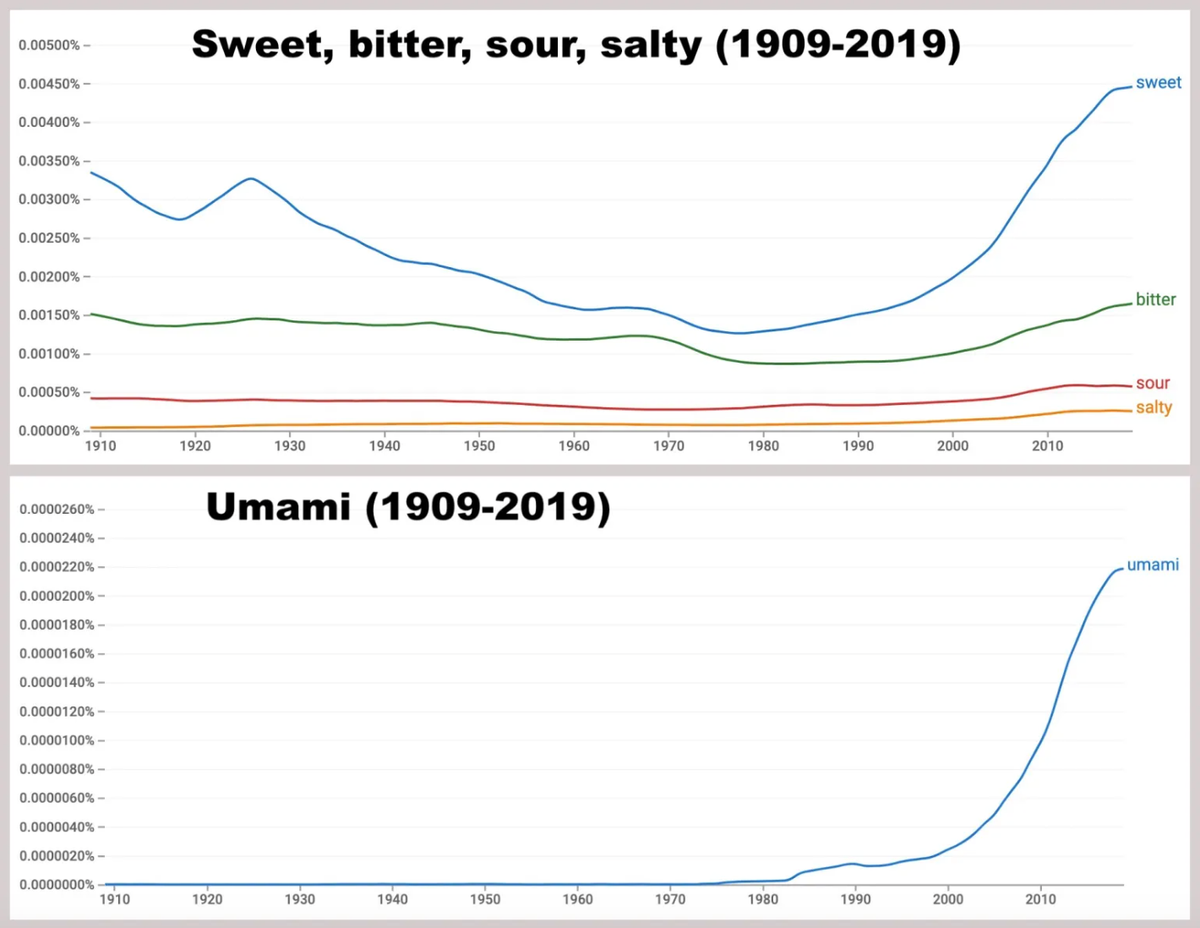

Interest took off only after 1980

Although umami was discovered in the early 20th century, it wasn’t until its later decades that the concept made inroads outside Japan. In the West, scientific interest in umami took off only after 1980. (See the graph.)

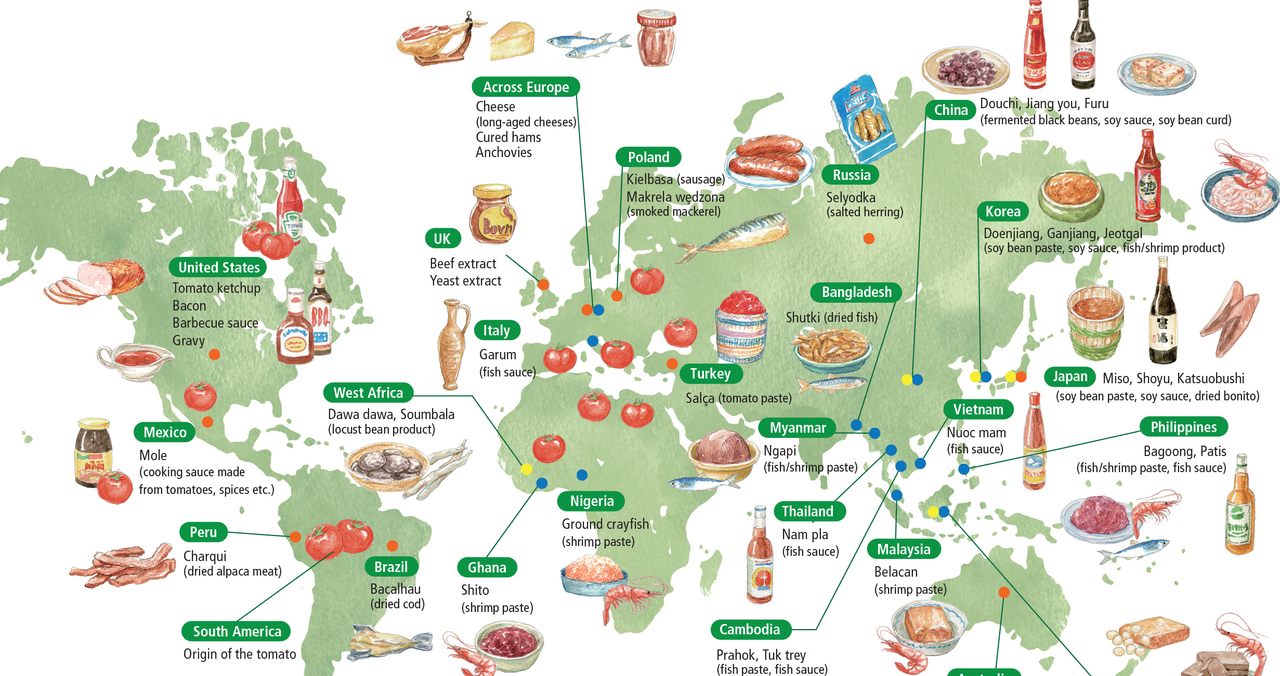

But as the map shows, umami has a global presence and a long history. Take for instance garum, a fermented fish sauce that was ragingly popular throughout the Roman Empire. One of the most intriguing “known unknowns” from antiquity is the exact composition of this Roman condiment, a distant ancestor to both Worcestershire sauce and ketchup.

Other more contemporary umami-rich foodstuffs across Europe include selyodka (or Russian salted herring), Poland’s kielbasa sausage, and yeast extracts like Marmite, which has been dividing opinion in the UK since 1902.

Anyone for dried alpaca meat?

In Africa, umami flavors find expression in foods like dawa dawa, a West African locust bean product, or shito, a shrimp paste popular in Ghana. Other fish-based umami foods can be found across Asia, such as shutki, a dried fish dish popular in Bangladesh, or prahok and tuktey, a fish paste and fish sauce from Cambodia.

Tomatoes are found the world over, but this umami-esque vegetable finds its origin in South America, as does charqui, dried alpaca meat from Peru. Higher up in the Americas, there’s Mexico’s mole sauce as well as bacon, barbecue sauce, and gravy in the U.S.

As it turns out, umami is no unknown stranger at our table, but an old and frequent guest. We’ll remember that, next time we ask to pass the ketchup.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook