Why a Computer History Museum Owns a Legendary Teapot

For computer-graphics researchers, it’s both a tool and a meme.

The Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California is home to many artifacts from Silicon Valley history. Amidst the ephemera of the Information Age, though, a humble white teapot sits on display.

Although it’s decidedly analog, the teapot is something of a sacred relic: It’s the original Utah teapot. Perhaps you’ve seen it before. It had a cameo in the first installment of the Toy Story tetralogy. It could be glimpsed, for years, atop a snaking pipe in a classic Windows screensaver. Sculptures of it can be found in parks from Texas to Poland.

The Utah teapot earned this place of honor by becoming indispensable to the development of the digital graphics that are a cornerstone of movies and video games today. Long before it belonged to the Museum, it was simply the teapot owned by British computer scientist Martin Newell. In the mid-1970s, Newell was a PhD student at the University of Utah, a leader in computer graphics research. In 1972, their Graphics Lab was the first to scan and render a real object: a VW Beetle.

During his student years, Newell faced a problem. He needed a new 3D model, but many existing mathematical models were too simplistic to test the techniques he was working with. According to several interviews, his wife, Sandra, suggested that he use their tea set, which included a white teapot. Inspired, Newell sketched out the dimensions of the teapot on graph paper, then entered its coordinates on a Tektronix storage tube, an early computer graphics terminal.

As the science magazine Nautilus notes, a teapot is an ideal canvas for 3D design. Teapots tend to be smooth and textureless, so even a simple render didn’t look too artificial. With its curvy shape, jutting handle, and spout, a teapot can also cast shadows on itself—making it the perfect self-contained object to test the creation of three-dimensional images.

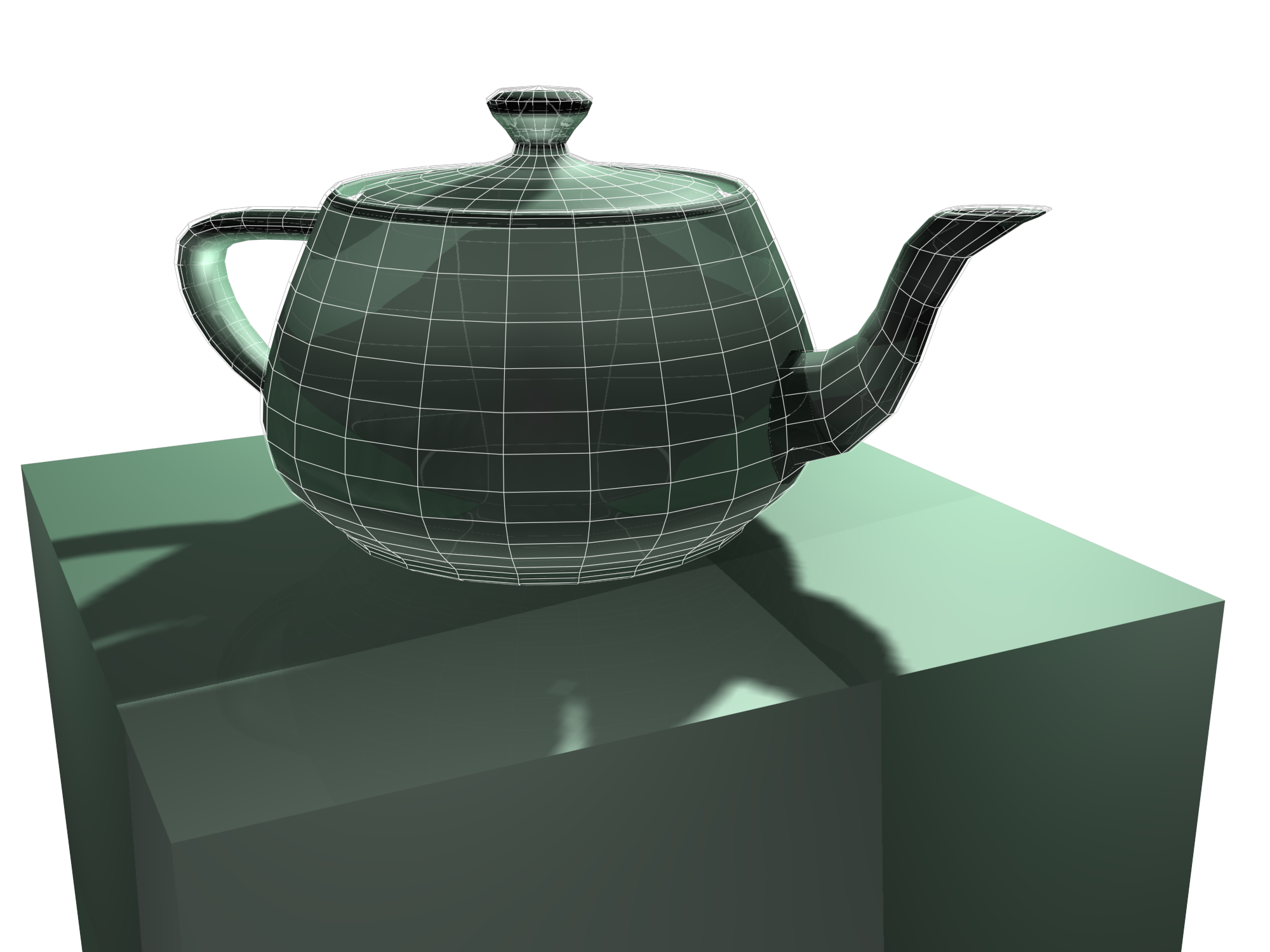

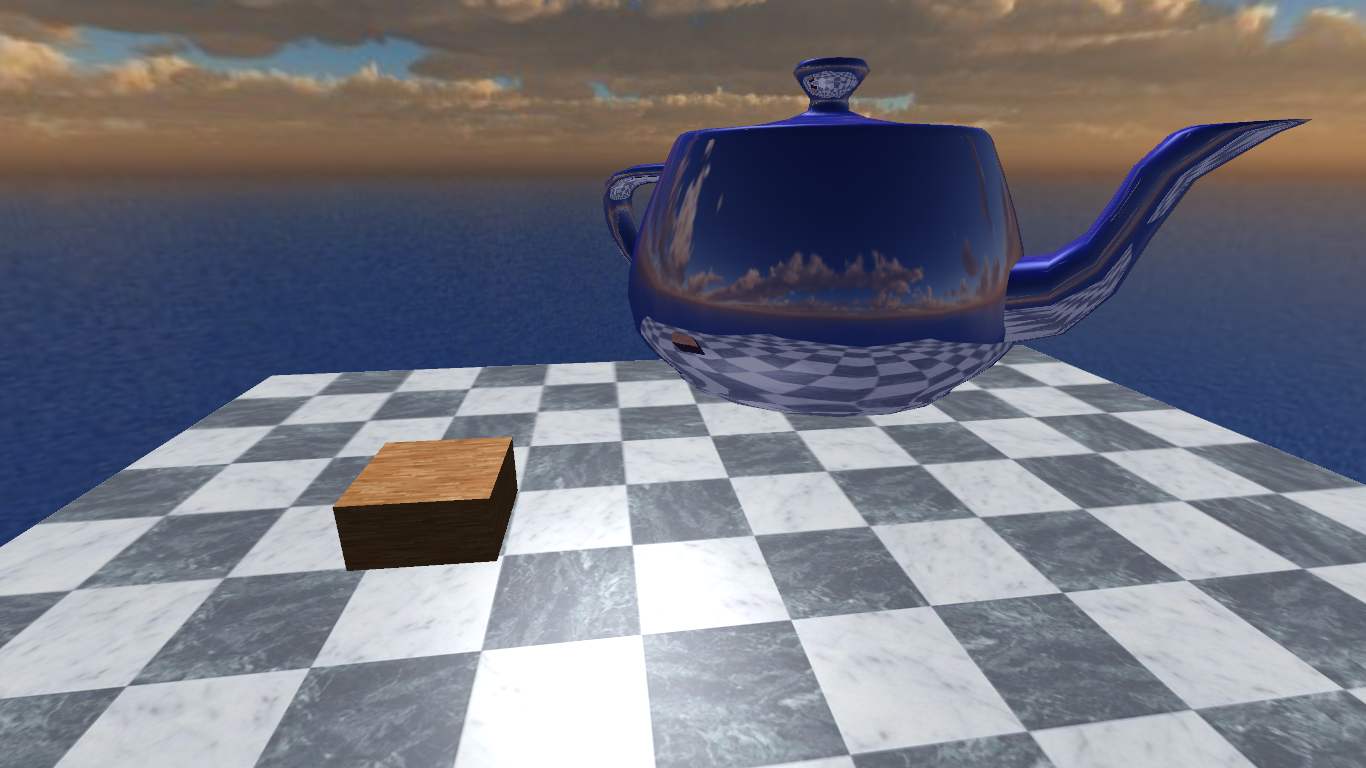

According to a University of Utah newsletter, the teapot became “one of the first widely available and photogenic curved-surface 3D models.” The data set Newell released for the computer-science community soon took on a life of its own. Soon, the standard rendition wasn’t even an exact representation of his Melitta teapot—a fellow researcher flattened the model by 33 percent. Since 3D models were fairly complex to make, computer-graphics researchers embraced the teapot with open arms. Over the years, the graphics community churned out computer-generated teapot images of every color, shape, and size. Due to its simple but distinct silhouette, the slightly squashed teapot model became a “crash test dummy” for 3D graphics learning, research, and experimentation.

It wasn’t long before the teapot turned into something of a meme. One 1987 paper jokingly proposed the addition of a sixth Platonic solid: the “Teapotahedron.” Pixar has handed out tiny, walking teapots to promote its RenderMan software, and even released an animated short featuring them. For animators, graphic designers, and artists, the teapot became both a classic tool and a beloved emblem. (On social media, pictures of real-life replicas are often met with joking wonder for their realism.)

As for Newell himself, he went on to an illustrious career in 3D imaging software. In light of his teapot’s digital immortality, he told the Salt Lake Tribune that he wished he had modeled it more carefully the first time around. Regardless, he donated his original teapot to the Computer History Museum. For years, the teapot’s legacy lived on in Utah, too, as the University of Utah held regular teapot-rendering competitions until 2017. Some of the eerily realistic scenes show how far 3D graphics have come from graph paper and a conversation over tea.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook