The Surprising Challenges of Making Things Vegan

It took Guinness, for one, years.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Meat is in the news a lot these days, it seems.

One study claims that animal fat might lower your cholesterol level, while a completely different one suggests meat affects your gut bacteria or causes blood clots.

And there are always stories about meat being where it shouldn’t be—notably, when the startup Clear Foods analyzed a bunch of hot dogs and found that many veggie dogs had remnants of meat on them due to the production process—enough to make any vegan lose his-or-her you-know-what.

And earlier this month, Guinness finally finished its years-long process of getting the fish out of its beer. When this news first gained notice a couple of years ago, a number of folks had a specific reaction: “Wait, they used fish bladders to make Guinness?”

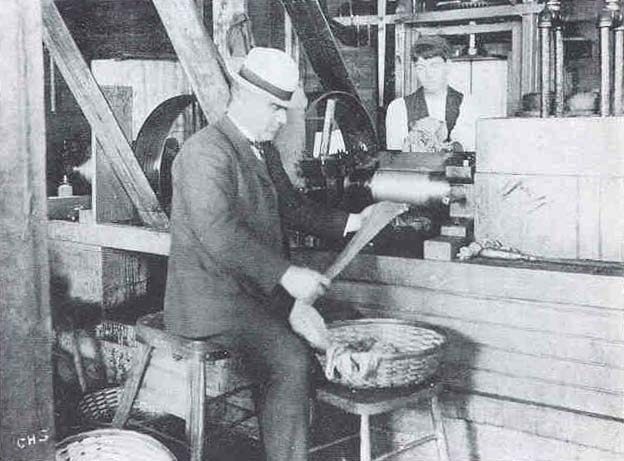

They know, they know, and the folks at the Guinness factory in Dublin have been working on cutting back their use of isinglass, the fish bladder long used to filter its iconic Irish beers.

“All brewers want to use the latest and the best technology, we’ve been researching for a decade about how we can reduce the amount lost in the filtration process so we were excited that this might work,” Guinness master brewer Stephen Kilcullen told The Times of London. “It’s great though that it means people who haven’t had a pint in a while can have one now.”

The announcement that the company was moving away from using isinglass in 2015 mostly had the effect of shocking lazy vegetarians concerned about things such as ethics, but even when Guinness was still using it, the amount was minute.

“The isinglass is retained in the floor of the vat but it is possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer,” the company explained in 2013. You can read more about Isinglass over at Smithsonian magazine.

Of course, Guinness is far from the only thing that vegans have had to worry about over the years.

For example, many vegetarians don’t take the full plunge towards veganism because they feel like they’d miss cheese too much. Problem is, some kinds of cheese happen to be made with a certain part of the cow that can’t be acquired without killing said cow.

The material, rennet, is procured from the lining of a cow’s fourth stomach, and is often used as a way to encourage cheese to curdle. Thanks to the declining cost of artificial or plant-based ways of doing the same thing, major food-makers have slowly moved away from relying so heavily on a material that must be acquired by killing a cow—and the list is growing.

However, there are a few kinds of cheese out there that require rennet to reach their full potential. One of those cheeses is Parmesan (formally known as Parmigiano Reggiano), one of the most popular kind of hard cheese there is.

Like a number of other traditional foods originally made in Europe, it has a protected designation of origin, meaning that it can only technically be called Parmesan if it’s made in a certain part of Italy, using a traditional production process. And sorry to tell you, eggplant Parmesan fans, rennet is part of that traditional production process.

Even without keeping the vegetarians in mind, this can create unusual complications for those that have diets that vary from the norm. For example, that traditional production process makes it difficult to make a kosher variation on Parmesan, because it has to go through two separate processes to ensure that it follows traditional standards as well as religious ones. It was so complicated, in fact, that it wasn’t until 2015 that a kosher variation on Parmesan debuted—complete with Star of David on the cheese block.

But if you’re vegetarian and hankering for some of the hard stuff, make sure you’re looking for “vegetarian Parmesan” or Parmesan-style cheese on store shelves. You’re not getting the real thing, but you’ll at least be able to live with yourself the next day.

The concerns with unexpectedly non-vegan options aren’t just limited to foods, either. Take the outer layers of paintball capsules, which are generally made of gelatin, a form of collagen generally derived from animal bones. (If you like Jell-O, geltabs, or marshmallows, you’re also a gelatin user.)

Tattoo ink, traditionally made of bone char, falls into the same category, and animal products are often used in maintaining that tattoo. However, there are some vegan-friendly alternatives out there, so you can still get an ugly tattoo if you would so like.

More surprisingly, guitars are made from animal parts in some cases, especially in the case of acoustic guitars. The nut and saddle of the guitar, two parts that hold the strings in place, are often made from bone, often not limited to one kind of animal. All of which is actually an improvement from the days when instruments were made using ivory.

And if you’re wearing Converse All-Stars, you may be skipping the leather, but you may not be out of the woods with your canvas shoes. Converse has traditionally shied away from calling its footwear “vegan.” The reason? Simply put, there’s a chance that the glue they use may be of animal origin, though they can’t be sure. Sounds reassuring, doesn’t it? The issue Chucks and their animal-derived glue has long been a matter of online debate. (The debate hasn’t stopped PETA from recommending Chucks to people.)

Of all the surprisingly non-vegan options out there, the most surprising might be fabric softener—which contains animal fat. No, really. Wired reported in 2008 that Downy uses dehydrogenated tallow dimethyl ammonium chloride, a material derived from the rendered fat of cattle, sheep, and horses, to keep your clothes silky smooth.

Or take condoms, another object known for not necessarily being vegan, though one that’s also made some strides in recent years, even if some folks, like the author Aine Collier—who literally wrote the book on condoms—remain skeptical.

“It wasn’t about the quality of the condom. Many were absolute crap,” she once told NPR of the phenomenon. “But people were buying them with the eye. They loved the packaging, because it fit the lifestyle they were trying to lead. And I think that’s exactly what this fair trade, biodegradable, green, vegan condom sales thing is all about. It’s just marketing.”

All of this is to say that veganism is challenging and hard to get perfect even in the best of circumstances, meaning that when it comes to manufacturing food or other products, we’re probably never going to get it 100 percent right. We’re already too far down the rabbit hole—a rabbit hole probably filled with many rabbits that have been turned into random chemicals for human consumption.

So maybe Guinness going vegan isn’t that big of a deal in the scheme of things, though consider the plight of folks like Paul Vogel, a founder of the Vegan Society of Ireland. He hasn’t been able to drink a pint of Guinness for nearly two decades. He recently got another chance, after he became one of the first people to drink a vegan pint of Guinness.

“It’s nice. I remember what it tasted like because it’s so distinctive. It’s creamy but has that bite,” Vogel told The Times of London. “I remember what it tasted like because it’s so distinctive. It’s creamy but has that bite.”

Still, Vogel later admitted that he’s probably going to stick with wine.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook