Virginia Woolf and the Complexities of Cottage Loaf

The famous feminist’s love for baking helps us understand her relationship with food, class, and mental illness.

What we most often remember from Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay A Room of One’s Own are her thoughts on real estate: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Yet Woolf also recommends something that’s less commonly cited, but no less important—a good meal. She writes, “One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.”

As a member of the modernist Bloomsbury Group—a collection of leading thinkers and artists of the early 20th century—Woolf certainly dined well, enjoying long lunches filled with philosophical debate and salade parisienne. While she employed cooks, Woolf came to enjoy baking later in life. Her specialty was a traditional British double-layered cottage loaf. “She could make beautiful bread,” recalled cook Louie Mayer, who worked for Virginia and her husband, Leonard, during the last years of Virginia’s life.

But Woolf’s journey into the kitchen was complex. She also harbored disdain for domestic labor and the women who performed it. “She initially, like the children of the class she belonged to, would not enter the kitchen,” says Francesca Orestano, a professor of English literature at the University of Milan, who has researched Woolf’s relationship to cooking. According to Alison Light, whose book Mrs. Woolf and the Servants chronicles Virginia’s relationship to domestic labor, this contradiction—between wanting to liberate herself from gender and class hierarchies, while perpetuating them—characterized much of Woolf’s life and work. Light says Woolf’s interest in cooking likely sprang from a desire to become independent—from patriarchy, from illness, and from a reliance on domestic workers. “That’s partly why I think she’s so joyful and exuberant when she learns to cook simple dishes.”

This joy is apparent in Woolf’s cottage loaf. “Cooked lunch today and made a loaf of really expert bread,” she wrote in a letter. In a diary entry, she celebrated a baking triumph: “My bread is really expert!” Thanks to the recollections of Louie Mayer, we have a record of Woolf’s baking process, though not a full recipe.

“In a way there’s nothing special about it—it’s just white bread dough,” says Neil Buttery, a British food history writer. What is distinctive, however, is the loaf’s shape, consisting of a smaller round loaf stacked on top of a larger one, likely designed to maximize baking space in traditional shelfless British brick ovens.

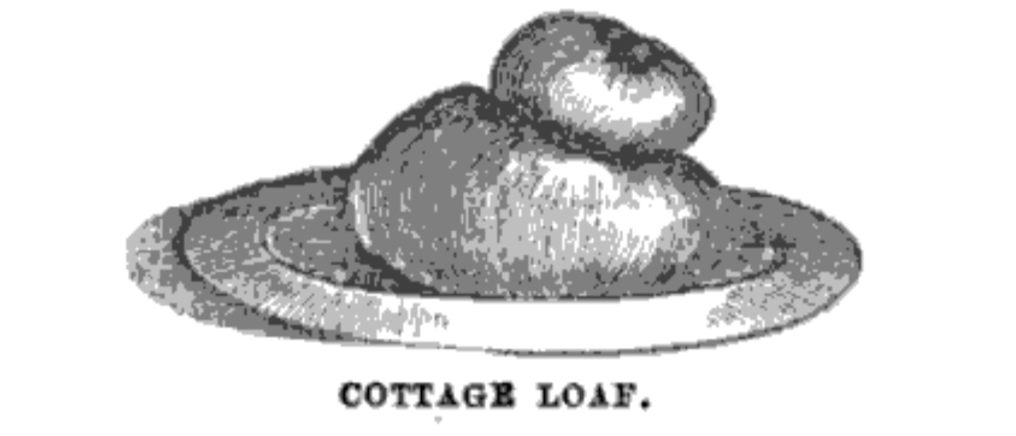

Cottage loaf first showed up in cookbooks around the middle of the 1800s—which, to Buttery, suggests that it was popular at least 20 years earlier. Mrs. Beeton, a popular Victorian cookbook author, prints an image of the loaf in her 1861 Book of Household Management. But she doesn’t include specific instructions on how to shape it, suggesting that such knowledge was assumed. Today, the loaf can be difficult to find in British bakeries and is the subject of significant nostalgia. Indeed, by the time Woolf started baking cottage loaf in the 1920s, the increasing adaptation of oil and gas stoves may have already started rendering it passé.

In contrast to her writing, for which she often pushed herself to the point of breakdown—Woolf’s baking was a source of simple pride. “I have only one passion in life—cooking,” she wrote in a 1929 letter to her lover Vita Sackville-West. “I assure you it is better than writing these more than idiotic books.”

Although she came to love baking, it’s quite possible Virginia never watched anyone make bread as a child. Born in 1882 as Virginia Stephen, she grew up in a rambling, six-story Victorian house with a large family. Her mother, Julia Stephen, who died when Virginia was 13, embodied the Victorian ideal of the “angel in the house.” Julia didn’t cook herself. Instead, she did charity work and managed a retinue of servants.

Basement kitchens represented wealthy Victorians’ desire to physically and socially quarantine the working class. “The basement was the inferno of the house, where the servants—the so-called denizens of the kitchen—toiled,” says Orestano. Upper-class people hated the smell of cooking, attempting to isolate themselves from this sign of the visceral labor that powered their luxurious lives. “You keep the servants and the ‘help’ separate; you don’t want them in your space,” Light says. “The smell of the cooking is kind of like the smell of them: it’s too close, it has to be tidied away.”

As an adult, Woolf devoted pages of her letters and diaries to vitriol about her cooks. She called her long-time cook Nellie Boxall a “mongrel” with a “timid spiteful servant mind.” She was often nasty to Nelly, with whom she had constant, dramatic fights, both women threatening to sever the relationship only to later make up. Of course, the vast imbalance of power between employer and domestic worker meant these were never equal fights.

Woolf struggled to fully acknowledge working-class women’s humanity in her fiction, too. In the sketch “The Cook,” Woolf attempted to paint an empathetic portrait of a domestic worker—but, in Light’s estimation, succeeded only in repeating maudlin upper-class stereotypes. “She wanted to look honestly at the things that often repelled her—including working-class women, who she wrote about in the most venomous, horrible way,” Light says.

When Virginia married writer Leonard Woolf in 1912, she could barely boil an egg. Barbara Bagenal, a friend who worked at Leonard and Virginia’s printing press, described a visit to their home in the late 1910s. “Virginia said that she did not know what we could have for supper because the woman who came in to cook for them was ill,” she wrote in a remembrance after Virginia’s death. When Bagenal said she could make scrambled eggs, “Virginia was amazed and said, ‘Can you really cook scrambled eggs?’”

While she couldn’t make food, however, Virginia could certainly enjoy it. In their early twenties, Virginia and her sister, Vanessa, moved away from snobbish Hyde Park and set up house in bohemian Bloomsbury. They fell in with their older brothers’ friends, the nascent Bloomsbury Group.

The Bloomsbury aesthetic was a sensuous rejoinder to maudlin Victorian morals. Many of them were queer, with what we today would call open marriages. Virginia, for example, had multiple romances with other women, a fact Leonard was okay with. And they loved to eat. “Despite a profound ignorance of all aspects of food preparation, the members of the Bloomsbury Group were the ‘foodies’ of their day,” writes Jans Ondaatje Rolls, author of The Bloomsbury Cookbook. The group favored French recipes, like chicken liver pâté and boeuf en daube, a Provençal beef stew that makes a luscious appearance in Woolf’s 1927 To the Lighthouse. Bloomsbury artists paid for the cooks they employed to take French culinary classes, and supported French cook Marcel Boulestin in the creation of his eponymous London restaurant, a version of which remains open.

The Bloomsbury Group’s expensive, cosmopolitan tastes were largely enabled by the racist economic exploitation of the British Empire. Virginia’s mother was born to a ruling class British family in India; Leonard started his career as a colonial administrator in what is now Sri Lanka. Colonial attitudes bled into Virginia’s writing, including her diaries, where, “She’s usually absolutely vile about other races, other ethnicities” besides white Christians, says Light. In fact, the Bloomsbury group partly gained their fame from an act of racism when, in 1910, Virginia and others dressed up in blackface and, claiming to be the “emperor of Abyssinia” and his retinue, talked their way onto a British naval ship.

Meanwhile, even as the Bloomsbury Group lingered over their epic “painting lunches,” Woolf struggled with food. Since at least the age of 13, when she had a breakdown following the death of her mother, Woolf experienced mental illness. Doctors called that illness many unlikely things—heart disease, rheumatism, even influenza—but “neurasthenia,” a generic Victorian-era “disease of the nerves,” was the diagnosis that stuck.

We can’t know the precise origins and diagnosis of Woolf’s mental illness. We do know, however, that she suffered from bouts of intense depression, often coinciding with the completion of a book; that she sometimes embraced what she called her “madness,” believing it to be tied to creativity; and that she often hated her condition, and attempted suicide on multiple occasions. We know that as a child, Woolf was sexually abused by her half-brothers, a trauma that she spoke out about and that many of her critics—and even biographers—dismissed.

And we know that Woolf’s mental health struggles were often tied to food. Barbara Bagenal remembered a lunch in the late 1910s when Woolf suddenly “began to flip the meat from her plate onto the table-cloth, obviously not knowing what she was doing.” Sometimes, Virginia refused to eat anything at all. Leonard and other friends “sat for hours on each side of her bed patiently persuading her to eat. They managed to spoon-feed her a little at a time, but sometimes she would hit the spoon away,” Bagenal wrote. “The most difficult and distressing problem was to get Virginia to eat,” Leonard Woolf wrote later. “If left to herself, she would gradually have starved to death.”

Virginia was never diagnosed with an eating disorder, but Emma Woolf, for one—Virginia’s great-niece, and an author who has written about her own eating disorder and that of her great-aunt—says she recognizes it as anorexia. In response to her struggles with food, Virginia’s relatives sent her to “rest homes” in the countryside, where she was forced to gain weight and forbidden from reading and writing.

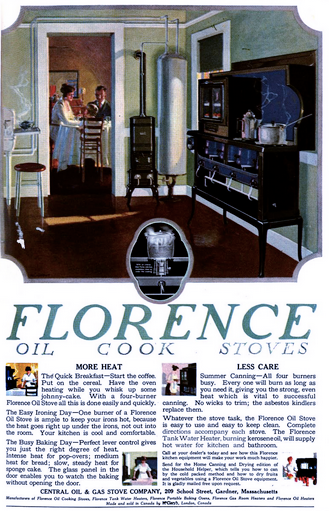

Sometime in the 1920s, Virginia’s relationship to cooking changed. Believing it to be good for her health, “Leonard encouraged her to do a certain amount of domestic work, such as cooking,” wrote the couple’s friend Alix Strachey. Both Orestano and Light argue that learning to cook was part of Woolf’s life-long quest for independence. “I think it’s part of a process of growing out of the strictures of her class,” Orestano says. The rise in oil and electric stoves, which replaced laborious coal- and wood-fired stoves, also made kitchen work more palatable for women who didn’t want to get their hands dirty. When the Woolfs acquired an oil stove, Virginia was ecstatic. “I have just bought a superb oil stove. I can cook anything,” she raved in a 1929 letter to Vita.

By the time Louie Mayer started working for the Woolfs in 1934, Virginia was so skilled at making cottage loaf, she could teach Mayer. “I was surprised how complicated the process was and how accurately Mrs Woolf carried it out,” Mayer later wrote. “It took me many weeks to be as good as Mrs Woolf at making bread, but I went to great lengths practising and in the end, I think, I beat her at it.” It’s possible Mayer was playing up Virginia’s skill in a display of class deference—it’s frustrating, after all, for a woman who’s just learned to cook to think she can teach a woman who had cooked for a living for years. Regardless, Woolf’s simple sense of accomplishment was a far-cry from the Victorian prohibition on domestic labor with which she’d grown up.

Around that time, Woolf’s letters to her lover Vita brimmed with culinary pleasure. “I’d like 3 days doing nothing but eat and sleep at Long Barn more than anything. An occasional kiss on waking and between meals,” Virginia wrote to Vita in June 1927 (Long Barn was Vita and her husband’s estate).

It’s a painful irony that, after having achieved some semblance of peace with food, Virginia Woolf died in 1941, during a period of rationing. World War II was raging, and the Nazi bombardment of London had convinced many that Nazi invasion was imminent. Leonard and Virginia, who were in a “black book” list of British dissidents the Nazis planned to murder (Leonard was Jewish; he and Virginia were both publicly antifascist), agreed that if England fell, they would both commit suicide. Food was so scarce that Virginia, who once had to be pushed to eat, fantasized about it. “Food became an obsession,” she wrote in her diary at the time. “I make up imaginary meals.”

Woolf died by suicide on March 28, 1941. The Nazis had not invaded. Instead, she wrote Leonard a note attributing her suicide to her lifelong struggle with what she called “madness.” She left behind a body of groundbreaking feminist thought. Yet Virginia’s legacy is simultaneously marred by her inability to connect her own liberation to that of working-class women and women colonized by the British Empire.

Food and cooking created a space that challenged that gap, a space in which Woolf was forced to learn from the women she overlooked. As much as Louie Mayer talks up her employer’s skills with cottage loaf, for example, it’s likely that Woolf learned to make the loaf from domestic workers in the first place. Meanwhile, prowess in the kitchen allowed Nellie Boxall, the cook whose epic fights with Virginia filled Woolf’s diary, to gain public recognition: After finally taking up work with a new family, she was featured alongside her beef recipe in a 1936 oil stove advertisement. Woolf may have been the famous writer—but these working-class women, too, were artists. “Food allows you to become an author,” says Orestano. “Food gives you authority.”

It’s fitting, then, that ultimately the most complete recipe we have of Woolf’s isn’t a luxurious boeuf en daube, but a cottage loaf. In a life filled with so much contradiction, there must have been something straightforward and satisfying about baking that simple loaf of bread. After all, even if she often didn’t heed her own insight, Woolf knew that what prevents marginalized artists from achieving recognition isn’t a lack of genius but a lack of nourishment. Virginia Woolf knew the importance of having one’s own shelter—and one’s own daily bread.

If you or a loved one are experiencing thoughts of suicide, support is available. You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 by phone or chat.

Virginia Woolf’s Cottage Loaf

Adapted from Neil Buttery’s recipe. I also consulted Louie Mayer’s remembrance of Woolf’s technique in Recollections of Virginia Woolf By Her Contemporaries and Elizabeth David’s interview with Mayer in the 1977 English Yeast and Bread Cookery.

3 cups bread or all-purpose flour

1 ¾ teaspoon salt

⅓ ounce or 3 teaspoon instant yeast

1 ⅓ cups warm water

1 ¾ tablespoon softened butter or oil

1. Mix the flour, salt, and the yeast in a large bowl. Make a well in the center of the flour and pour the warm water and butter into it. Mix until a loose dough begins to form and then bring the dough together with your hands.

2. On a lightly floured or oiled work surface, knead the dough until it feels tight and springy under your hands, about 10 minutes. You can also knead it with a dough hook on a mixer, about five minutes.

3. Roll the dough into a tight ball, put it in an oiled bowl, cover it, and leave it to rise until it doubles in volume. This can take between one and three hours depending on the temperature in your home. Generally, warmer temperatures make dough rise faster; Louie Mayer left her dough to rise on an overhead dish rack.

4. When ready, punch out the air and cut away a third of the dough. On a lightly-floured work surface, form a ball with the dough by pulling the sides down then tucking your hands under it, twisting slightly to make a tight ball. Repeat with the other piece of dough.

5. Sit the small loaf directly on top of the large one. Then, flour the first three fingers of one hand and plunge them through the dough until they hit your tabletop. Repeat one more time and your two pieces should be fused together. You can also make a few slashes with a serrated knife, about a quarter of an inch deep, around the top and bottom loaves for a classic cottage loaf look.

6. Put the loaf on a baking tray and cover it with an upturned bag or bowl. Leave it to rise again until it’s twice the size, but still springy to the touch. Elizabeth David recommends 10 minutes, and says it’s better for the cottage loaf to be slightly under-risen, rather than over-risen, in order to maintain its shape. If you see that your loaf has begun to lean precariously to one side, give it a little nudge and get it straight in the oven. Heat the oven to 420 degrees Fahrenheit.

7. Place the loaf in the oven. Louie Mayer—and therefore, perhaps, Virginia Woolf—put the loaf directly into a cool oven. The gradual increase in heat allows for another rise and helps the loaf form a nice crust. Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, or until the loaf has formed a golden-brown crust and smells delicious. Don’t worry if your top loaf leans to the side like a jaunty hat—that’s how cottage loaves often look, including in Mrs. Beeton’s 1861 cottage loaf illustration.

Gastro Obscura Notes

- In her cookbook, British bread expert Elizabeth David suggests adding one part whole wheat flour to three parts white flour.

- In Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management of 1861, one of the earliest known references to cottage loaf in print, Mrs. Beeton suggests using a mixture of water and milk as the liquid for the loaf. According to Buttery, this yields a softer loaf.

- Some recipes include fat (butter or oil), while others do not. Buttery says this is optional and that the addition of fat helps the bread keep longer.

- According to Louie Mayer, after Virginia Woolf made her cottage bread dough, she “returned three or four times during the morning to knead it again.” Buttery says this is likely due to the protein and gluten content of the flour. Flours with a lower protein content, like today’s all-purpose flour, develop less gluten; flours with a higher protein flour, like today’s bread flour, develop more gluten. Buttery says contemporary bread bakers using all-purpose flour may want to incorporate Woolf’s extra rises and kneads in order to further develop the gluten. I used all-purpose flour and only kneaded once, as per the recipe above, to very tasty, though admittedly slightly cakey, results.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook