The U.S. Government Once Nuked a Bunch of File Cabinets

Operation Teapot’s “Project 35.5” tested record-keeping under extreme circumstances.

On January 25, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the Doomsday Clock—a metaphorical tool that measure threats to humanity—is now closer to midnight than it’s ever been, saying that “major nuclear actors are on the cusp of a new arms race.” On Saturday, January 13, the citizens of Hawaii went through a 38-minute panic attack when authorities accidentally sent a missile alert to the entire state. Sales of anti-radiation pills are spiking. It’s safe to say that America has nuclear disaster on the mind.

With such thoughts come questions, many of which are quite existential, and thus difficult to answer. But luckily for worried souls, there’s one practical thing the government figured out decades ago: in the event of a nuclear attack, what’s the best way to store your files?

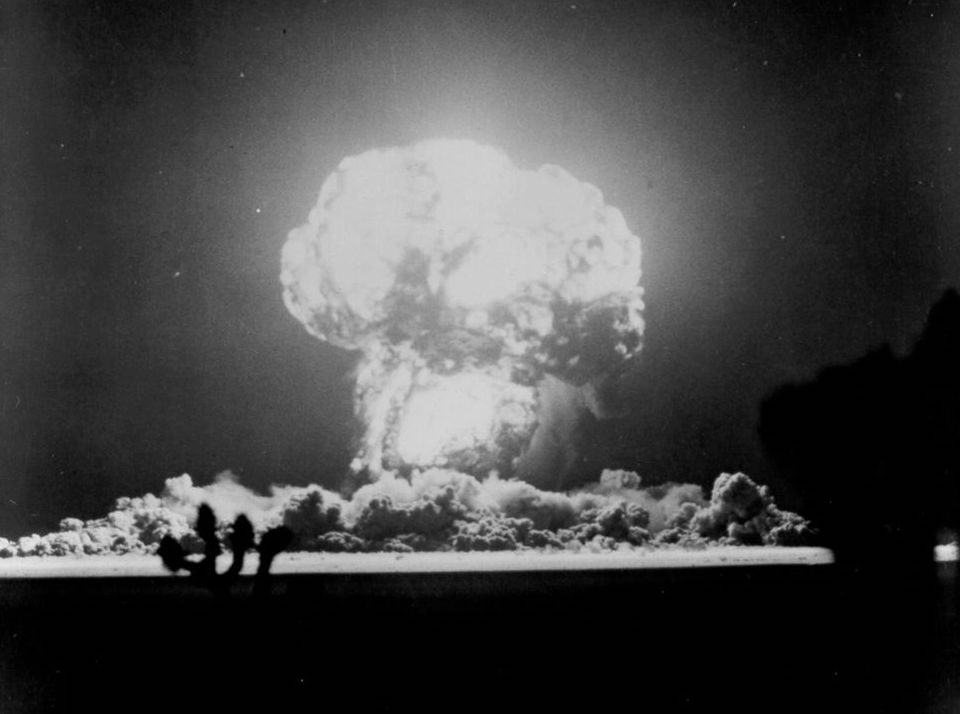

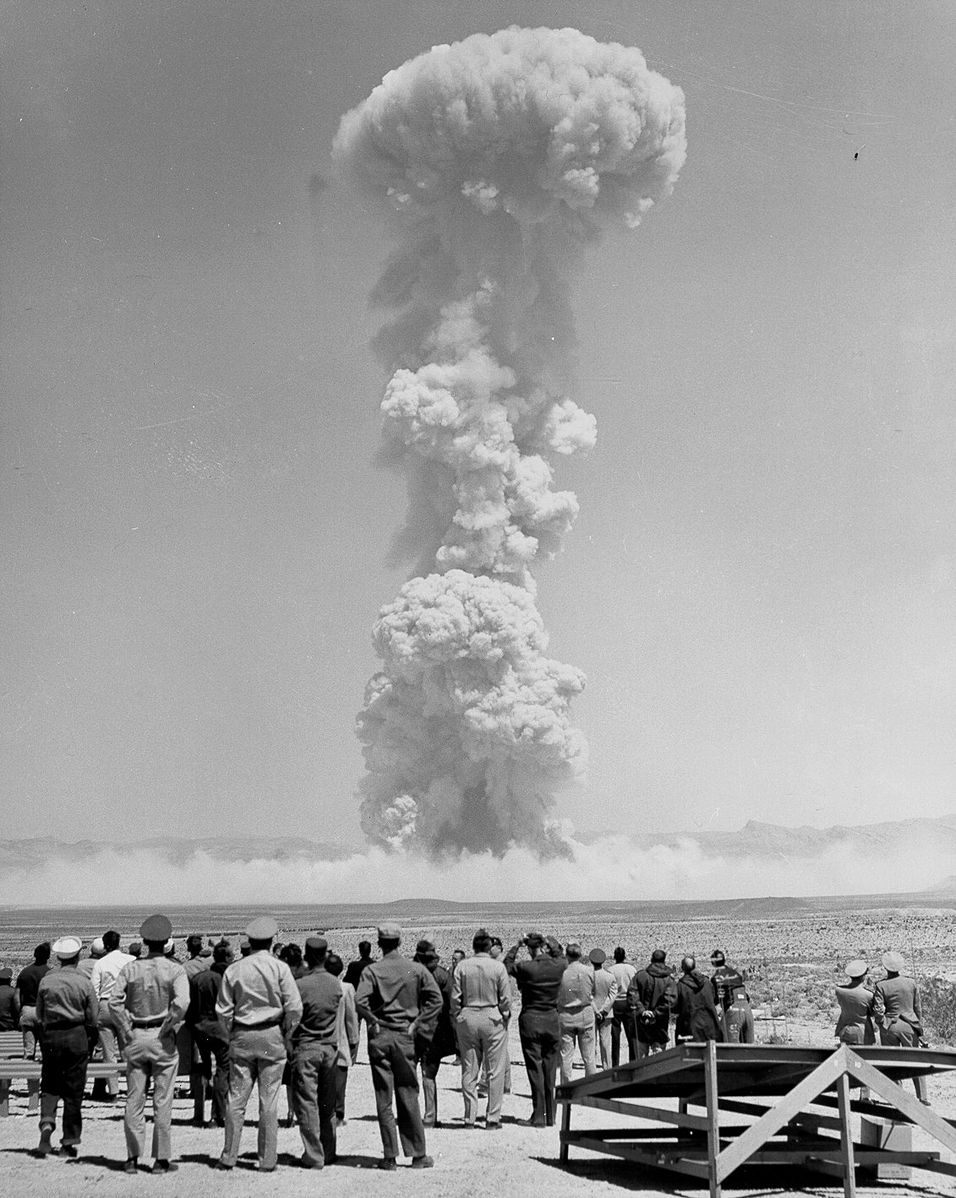

Let’s back up. In 1955, the Department of Defense began Operation Teapot, one of dozens of nuclear experiments that have been performed at the Nevada Test Site since the late 1940s. Operation Teapot consisted of 14 separate explosions, each of which provided the DoD with the opportunity to assess various outcomes of interest.

A test called “Wasp,” for example, was meant to show what would happen if a nuclear device detonated at low altitude. For another, called “ESS,” an 8000-pound bomb was exploded underground, to see how large of a crater it would make. (Many of the tests had quotidian names, like “Bee” and “Zucchini,” which are illustrated on an incongruously playful diploma given to participants.)

When it came time for the second-to-last test, called Apple-2, the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) got involved. The United States was in the grip of the Cold War, and the possibility of an attack on American soil seemed—then, as now—frighteningly real. In the words of journalist June Collins, their mission, called Operation Cue, was meant to “test the effects of an atomic blast upon the things we use in our everyday lives.”

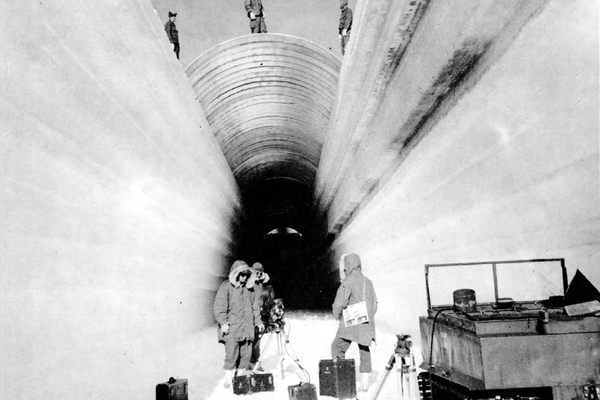

To this end, the FCDA set up a fake village in the test’s vicinity. It built houses out of different materials, populated them with mannequins dressed in different types of fabric, and put cans of food around to see just how irradiated they would get. The FCDA also paved fake streets, set up a radio station and a telephone system, and scattered the so-called “Survival Town” with automobiles and fire trucks.

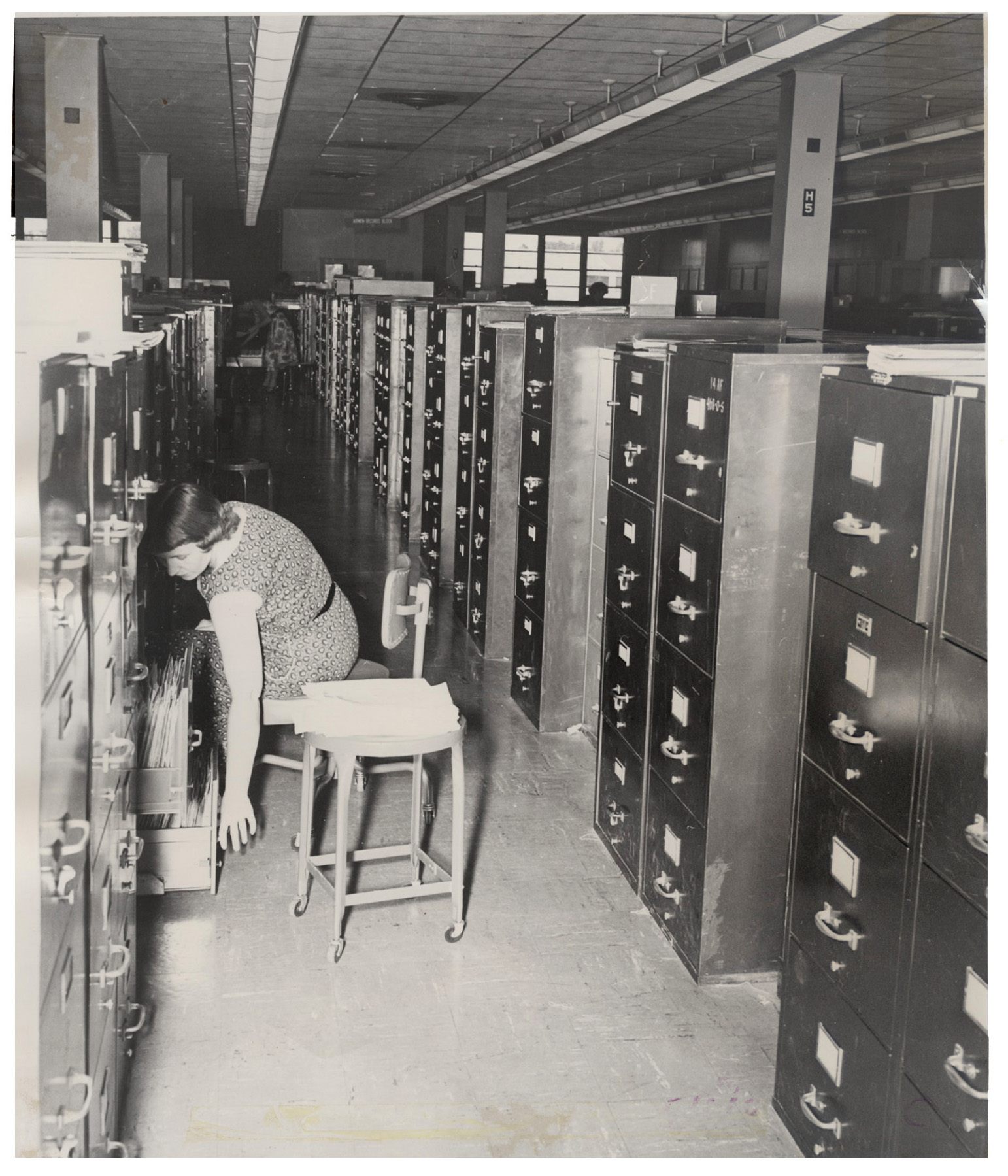

But they didn’t stop there. While they were at it, they figured, they might as well nuke some file cabinets, too. For Project 35.5, “Effects of a Nuclear Explosion on Records and Records Storage Equipment,” the FCDA teamed up with the National Records Management Council, several companies that made safes, and a superintendent from Western Union. They filled various storage vessels with various types of media, scattered them at various distances from Apple-2’s Ground Zero, and waited to see what would happen when the bomb dropped.

The project’s official report—which was first released in June of 1958, and was uploaded by nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein on his blog, Restricted Data, in 2011—explains the rationale. “Business records are the memory of an organization,” it reads. “Preservation of important business records in a disaster can help ensure survival of managerial direction and continuity of enterprise.”

“If essential records are available after a catastrophe, management has the information required to resume operations with minimum delay.” In other words, though meetings may be cancelled in the event of Armageddon, the show as a whole must go on.

The report also lays out the process, which was quite thorough. The guinea pigs included “a complete variety of records storage equipment,” such as file cabinets, steel shelving, corrugated cardboard boxes, and different classes of safe. Inside were materials ranging from photographic film to paper letters to telegraph tape. These were then put in assigned locations, some inside or next to structures, and some completely exposed. For one subtest, the group put samples of four different types of paper—“new rag, old rag, soda sulfite, and purified sulfite”—in various Survival Town basements and garages.

Apple-2 went off early in the morning on May 5, 1955. As soon as the radiation had dissipated, the team went in to check on its records. Close-range, open-air results were not encouraging: Seven out of the eight storage vessels placed nearest to Ground Zero did not survive. “Although small pieces of metal were scattered about the test site, the remains could not be identified,” the report reads. “The contents of these seven units were not found.”

Five safes placed slightly farther away were also useless. Some reached an internal temperature of over 490 degrees Fahrenheit, which burned their contents to smithereens. Others simply exploded. One left “motion picture film … strewn across the desert floor.” File cabinets at similar ranges “were so badly scorched and damaged as to be rendered unusable.”

Money chests fared far better. One, originally placed just a fifth of a mile from Ground Zero, was found about 350 feet from its original location, burned and with a broken lock. It had done its job, the report says: “The contents, which were in excellent condition, included a gold watch case, paper, United States postage stamps, loose microfilm, and microfilm in a sealed can.” In general, those storage vessels shielded by buildings survived intact, especially when they were in basements—although these, as the report points out, were then vulnerable to “debris, fire and water.”

Based on these results, the FCDA determined that “records housed within the type of equipment tested would survive if protected by some type of structure.” As most people and enterprises don’t keep their file cabinets out of doors anyway, you might consider this test proof that the status quo is pretty solid. Decades later, records storage professionals still turn to the test for guidance: as the industry publication Information Management put it in a 2008 article, “the final report for Operation Teapot outlined a classic vital records program.”

This success seems a bit beside the point. As Wellerstein put it on his blog, “How survival of ‘managerial direction and continuity of enterprise’ was supposed to take place when all of your managers and employees and customers were dead, I’m not sure.” Still, if you find yourself shopping for potassium iodide, maybe consider investing in a money chest, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook