What Is Walden Pond?

Its cultural meaning may be calcified—but off the page, it’s changing fast.

On a typical summer day at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts, swimmers pull themselves from shore to shore, safety floats in tow. Planes buzz by overhead. A few times an hour, silver and purple commuter trains rocket through the trees, on their way to or from the center of Boston. Even the back shore, far from the beach house, is crowded. A man flays a fly-fishing rod back and forth, seemingly oblivious to the couple canoodling behind him. “I can see you guys,” he reassures them after a few dozen whips.

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau published Walden: Or, Life in the Woods, an account of the two years he spent living in a one-room cabin on the shores of Walden Pond. The book has since cemented itself in the American consciousness—as well as on many American school reading lists—and the words “Walden Pond” now conjure, in the imaginations of many people who have never been there, stillness, self-sufficiency, and untouched natural majesty. Even as people have reassessed the book and its author for living less independently than he claimed, the pond itself has largely escaped such scrutiny.

But the real Walden is different from this Walden of the mind. The actual body of water has lived through centuries of change and use. These days, it’s often full of people, our sporting equipment, our trash, and our excretions. The historic pond reflects us relentlessly, and the image often shifts. So I spoke to a photographer, a scientists, and a computer game developer, and asked them: What is Walden today?

The Photographer

As of press time, Walden Pond has 176 reviews on Yelp. Many of these are positive. People call the pond “majestic,” “serene,” “bucolic,” “inspiring,” and “internationally acclaimed.” They give high marks to the the visitor’s center, the bathrooms, and the beach house, all of which are the work of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), which has managed the site since it became a State Reservation in 1975. (They also like the statue of Henry D. himself, who is posed with his left arm outstretched and his hand open, as if pleading with people about something, perhaps to leave him alone.)

Others find themselves less impressed. Reviewers have docked stars for “rude people,” the slant of the beach, the parking fees, and the firm anti-pet policy (“I think HDT would have let me bring my dog”). “I get the historical importance of this place but I have to say I was a bit underwhelmed,” wrote one visitor who came earlier in 2018.

“Walden—it’s its own cultural meme,” says S.B. Walker, the photographer behind the 2017 book Walden. “Everybody has an idea. When people go there, there’s almost a little bit of disappointment, I think.”

Every year, Walden Pond hosts hundreds of thousands of people. Most—half a million, some years—come in summer. A scroll through the pond’s official Twitter account reveals that the whole place ended up “closed for capacity” for 11 days this past July, often before noon. “No walk-ins or drop-offs,” the Tweets warn. (Savvy locals ignore all of this and go in through a back trail marked “Not a Public Entrance,” often risking a ticket by parking at nearby Concord High School.)

Walk around Walden on a hot day, and you’ll certainly find transcendentalists and English teachers. “People will go there to do spiritual or quasi-spiritual activities,” Walker says. “People come to do yoga, and other things that are mindful”—to live deliberately, at least for a little while, before they have to dash out to beat rush hour. Once I saw someone dressed in purple velvet, shooting a video for her philosophy Youtube channel about the place of nature in contemporary life.

But other motivations (and outfits) are more prevalent. “The majority of people are there to cool off during the summer,” says Walker. “They’re there to swim.”

Walker grew up just southeast of Concord, in a similarly small town called Lincoln. He got into Thoreau in college—his gateway drug was a deep cut, an 1862 Atlantic essay called “Wild Apples”—and when he returned from a stint abroad in Greece, he found himself wandering around Walden, remembering his own childhood and thinking about transcendentalism.

He was interested in the clash between what people expected from Walden and what they got—and whether this was really a clash at all, or just a choice of how to pay attention. “Even when [Thoreau] was there, the railroad ran 20 feet from the pond,” he says. “People were cutting wood in the forest, and cutting ice out of the pond in the winter. It’s only been in his telling of it that somehow, it comes across as more remote than it is.”

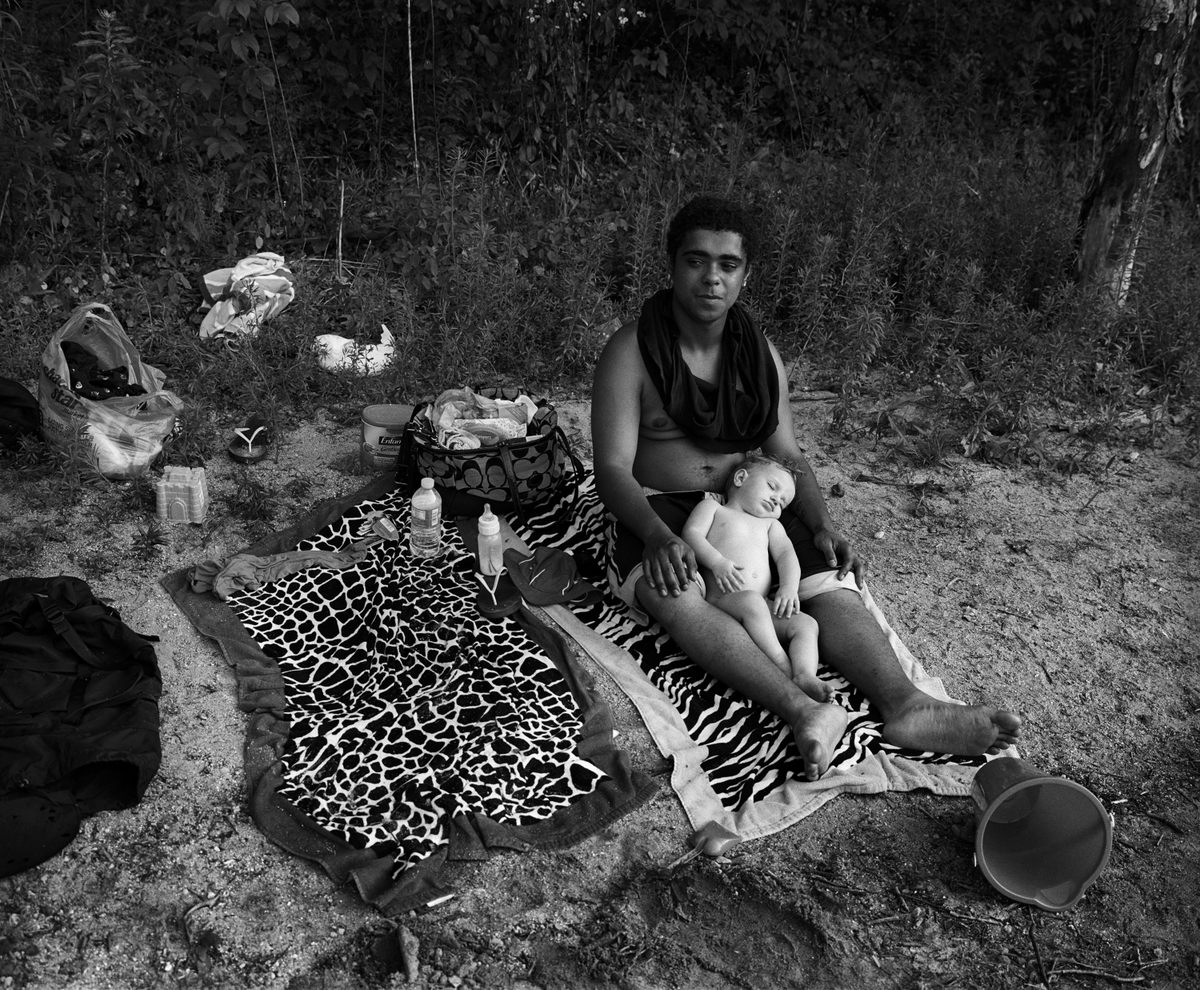

In 2009, Walker decided to start taking photographs. For the next four years, he visited often, getting to know the regulars and collecting small, illustrative moments. “So much of Walden’s place in America’s moral geography has to do with how we relate to our surroundings,” he says. In his own Walden, Walker captures the various forms that such relating actually takes today. A Target bag floats on the surface of the lake. Kids play on the railroad tracks, which are just a few yards from one of the pond’s edges. A man in a beach chair reads about toe fungus.

Written out, it sounds a bit bleak. But each shot is suffused with a sense of eerie magic—of the possibilities, aesthetic and emotional, of these new relations. People’s belongings are strewn through the underbrush and almost meld with the landscape. In 2010, after heavy rains flooded the beaches, Walker captured a couple kneeling on a submerged bench. A downed ice cream cone, photographed in early fall, brings to mind a winter shot of cracks spiderwebbing across the ice.

“There were a lot of times when I’d walk around the whole pond and I wouldn’t take a single picture,” he says. “Then there were days when there were real sparks… real patterns were emerging.” In Walker’s telling, this possibility, rather than solitude or self-sufficiency, is one of Thoreau’s main lessons: “If you are open and perceptive, there’s just an incredible mystery behind every little thing.” In other words, if you’re looking for two Waldens—the crowded, flooding, too-sloped one that exists in the world, and the untouched one that exists in peoples’ minds—“they’re both there.”

The Scientist

Curt Stager, too, sees several Waldens at once. A professor of natural science at Paul Smith’s College in New York, Stager reads the past lives of lakes through sediment cores—long, cylindrical samples of what lies at the bottom of them. He often studies bodies of water around the Adirondacks, assessing how climate change has affected them over the past millennium or so.

But a few years ago he branched out—“I needed a comparison site,” he explains—and he and his students spent a summer coring in Concord. When I ask him why, of all the gin joints, he chose Walden Pond to focus on, he answers tautologically. “Because it’s Walden Pond!” he says. “What’s the one lake in New England that you’d want to study?”

Like most lakes, Walden Pond has a long geological past and a shorter, somewhat more dramatic anthropogenic one. (“We always think of Thoreau, but that’s only 150 years ago,” says Stager. “That’s a hundredth of the history.”) It’s a glacial kettle lake, and was first formed about 15,000 years ago, after a massive ice sheet called the Laurentide retreated from New England and left a bit of itself behind, embedded in the bedrock.

That iceberg “slowly melted down into a gritty pit like ice cream in a cone,” as Stager put it in his recent book, Still Waters: The Secret World of Lakes. “Eventually, only the cone remained, exposing the surface of the local groundwater table.” Walden’s water—which stretches 102 feet down in one basin, making it the deepest natural lake in Massachusetts—now comes about half from groundwater and half from snow and rain.

In an article for Nautilus, Stager imagines how people might have used the pond millennia ago. Three thousand years ago, “people of the late Archaic to early ‘Woodland’ cultures used some of the earliest clay pots while they camped and cooked beside the lake,” he writes. A thousand years ago, Native Americans were seasonally burning forest underbrush and planting maize. Pollen from other core samples reveals that they might have started planting rumex, an edible herb, around the pond in the 16th or 17th centuries.

Then, in 1635, the British came. As Stager and his coauthors summarize in a recent paper, over the next few centuries, as they colonized Concord, the lands around the lake began to change more rapidly. Trees were logged, drowned by high water levels, and burned in forest fires—often thanks to sparks cast off by steam engines, which started chugging through after the Fitchburg Railroad was built in 1844.

By the time Thoreau moved in a decade later, the lake and its surrounds were far from pristine. In Walden, although Thoreau famously describes himself as living “a mile from any neighbor,” he also talks about hearing the trains go by, borrowing an ax from a man who lived in a nearby shantytown, and smelling a dead horse left in a cellar hole.

After Thoreau’s time there, the surrounding towns continued to grow, bringing new visitors who wanted to do new things. Again, Walden Pond absorbed the impacts, sometimes literally. In the early 1930s, Stager et. al. write, “a new footpath to Thoreau’s cabin site … caused large amounts of soil to wash into the lake.” Swimming beaches and their accompanying infrastructure were created and torn down several times. In the 1950s, Concord established a 35-acre town dump a few hundred yards away; in 1968, the state dosed the water with rotenone, killing the pond’s fish in order to refill it with more “sporting” varieties, like rainbow trout.

All these shifts left their mark, but one was bigger than others. When Stager and his team pulled up their cores, “we found a big change in the ecology of the lake starting in the 1930s,” he says—a tipping point that mirrors previous studies. This timing doesn’t match up with rising temperatures, increased precipitation, or decreased winter ice cover, all of which occurred closer to the 1960s. Rather, Stager says, “that’s when the use of the pond [itself] was increasing a lot.”

Starting around that time, Stager and his team found four telltale species of diatom, single-celled algae that thrive in phosphorus-heavy environments. While digging through slightly older research, they found a U.S. Geological Survey study that pinpointed the source of this phosphorus: It’s pee. Human pee, to be more specific. Currently, “about half the summer phosphorus is from swimmers,” Stager says, diplomatically.

Understanding Walden’s past also helps Stager predict its future, and all this urine could mean we’re in for a problem. The more phosphorus in the water, the more microorganisms can thrive there. The more microorganisms, the cloudier the lake. This murk could also cut off light to the mats of green algae at the bottom, which Stager describes as “underwater meadows,” and which are also crucial to maintaining water quality. If we lose the meadows, the paper warns, we risk hitting “an ecological tipping point that could severely and permanently reduce the clarity of the lake and degrade its recreational value.”

Meanwhile, the stakes are rising with the temperature. Climate change is coming for Walden Pond, as it is for all of us. (Another Walden-adjacent scientist, Richard Primack, has been using observations from Thoreau’s journals to pinpoint just how quickly that’s occuring.) “It’s going to get warmer there,” says Stager. “That tends to make lakes more vulnerable to algae blooms.” It might also get either wetter or drier, he adds, “both of which could do it, too.”

Hotter temperatures also mean more swimmers, which means more pee, more phosphorus, and more murk. Stager and his colleagues ended their paper with a strong recommendation: “construction of a separate swimming pool facility nearby to relieve pressure on the lake.”

Originally, Stager told the Boston Globe that banning swimming at Walden altogether would be even better. Then, during a meeting with the Thoreau Society, he learned that the state can’t do that. “So I recommended that they just restrict where they do it, so it’s just where the swimming beach is—and the bathrooms—and not allow swimming elsewhere,” he says.

“When I mentioned that, other people got all upset because they’re competitive swimmers. They love to swim across the lake.” What about putting bathrooms on the other side of the lake? “The DCR people rolled their eyes, yeah right! How are we going to service those on the remote road?”

“Everybody cares about it,” Stager concludes. It’s just difficult to figure out what to do. But it’s imperative, he believes, to do something. “The big picture is learning how to see ourselves as part of nature …. It’s not that the lake is in trouble because we’ve touched it, and our touch is evil or a pollutant. It’s just that we have the option of determining or controlling what our influence on the lake is. Why in the world wouldn’t we want to have a positive influence?”

At the moment, all is not lost. Stager’s analysis indicates that, compared to 20 years ago, things are pretty much holding steady. “The take-home message is, the DCR has done a great job of stabilizing the lake,” says Stager. “But everybody’s going to have to work harder in a warming future to keep it the way it is—to avoid the risk of loving it to death.”

The Game Designer

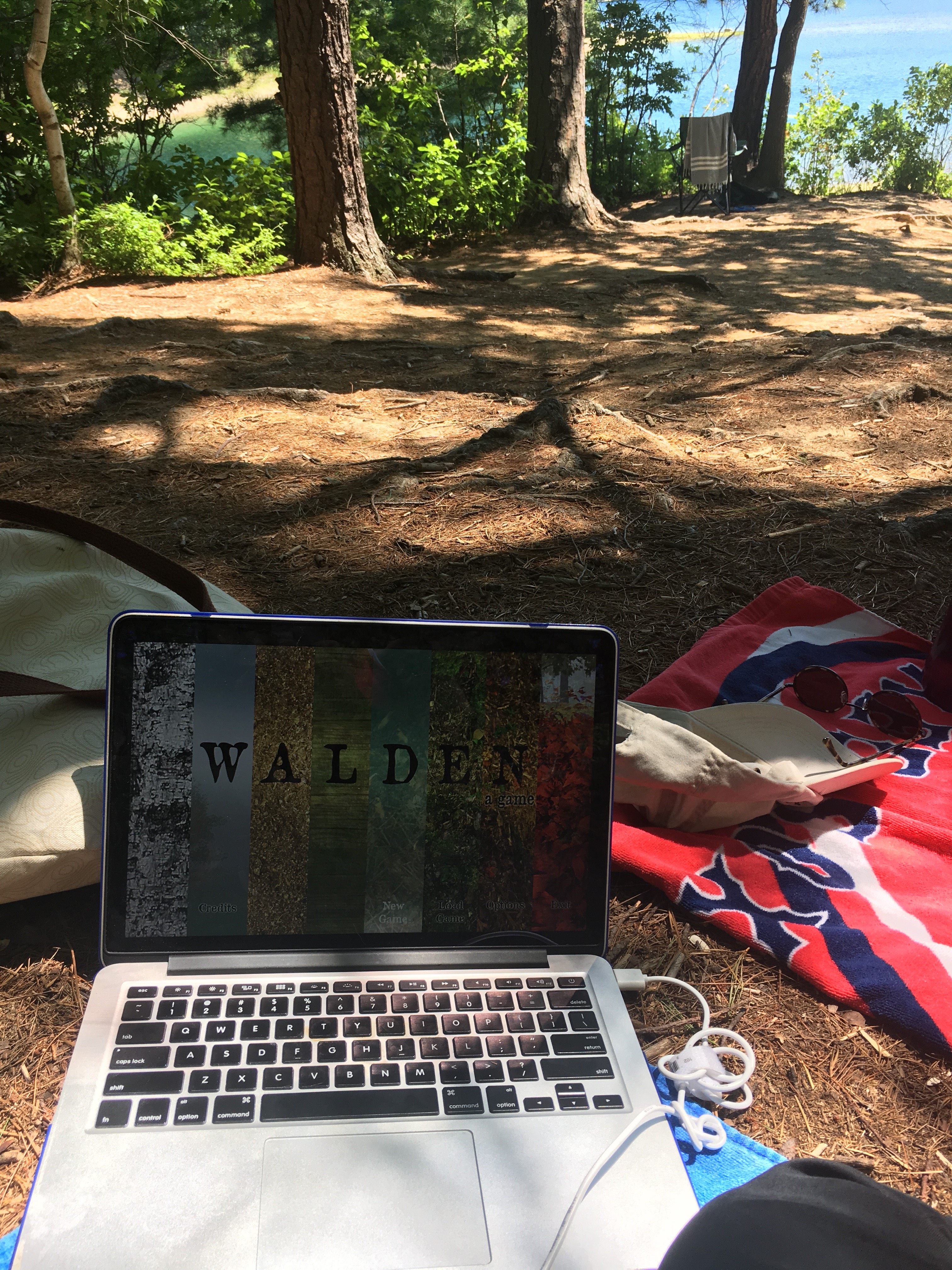

There is one worry-free way to go to Walden, kind of. Last year, after a decade of work, a group of game developers at the University of Southern California’s Game Innovation Lab, released Walden, a game. It’s a transcendentalist RPG, set on and around the pond. You don’t have to deal with the crowds, and you don’t have to moralize about your own bodily functions. Your dog can even watch over your shoulder if he wants.

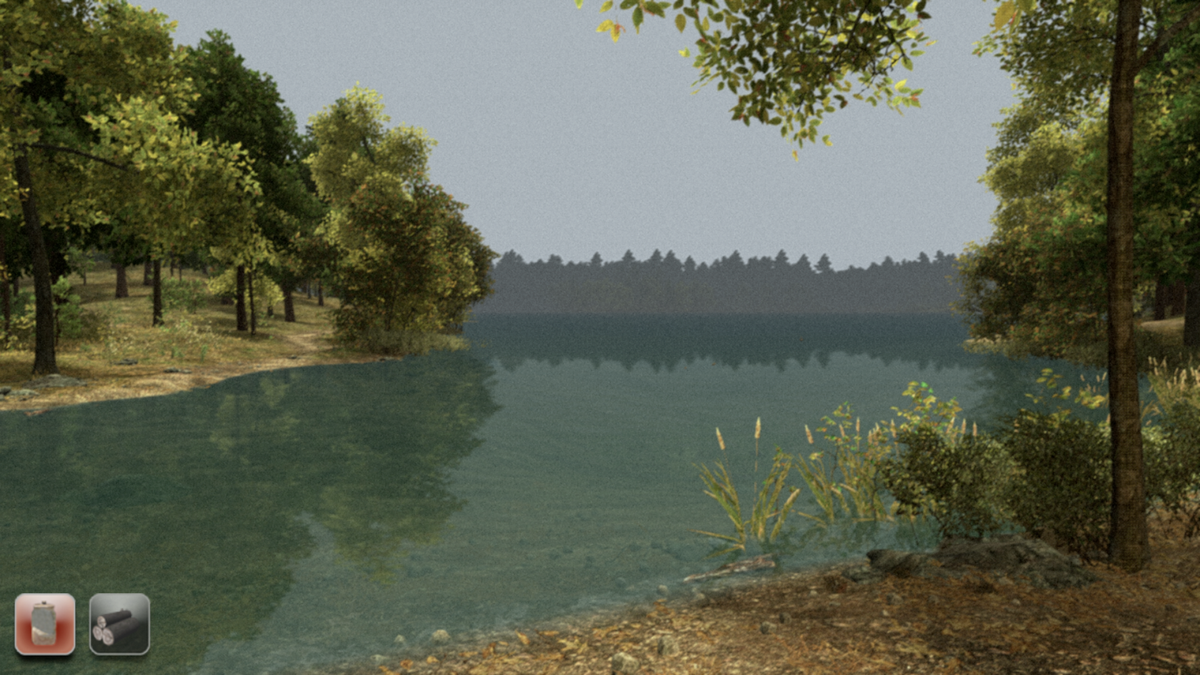

In the game, you are Thoreau, living your Walden life from the summer of 1845 to the spring of 1846. Your days are filled with tasks both practical and transcendental: you have to find food and chop firewood, but you also have to constantly top off your “inspiration,” which you can get from watching animals, hanging out alone, or reading Homer. Although you play as Thoreau, and often hear his words read aloud, you don’t see him—just his hand when it reaches out to gather blueberries, or pick up an arrowhead off the path. The real stars are Walden Pond and Walden Woods, which have been meticulously, virtually reconstructed.

“Several times people came into the lab, and without even knowing we were making a game about Walden, would say things like ‘Hey, is that Walden Pond?’” says Tracy Fullerton, the head of the lab and the game’s lead developer. “When locals are able to recognize the landscape just like that, you know you’ve nailed it.”

While putting the game together, Fullerton visited the real pond frequently. She consulted with historians and scholars, as well as with Thoreau’s writings, to get a good sense of the layout and of the ecosystem’s other inhabitants. She took photos of the woods and water at all different times of the year, so that the team could get across, pixel by pixel, what she calls “that sense of granular change in all of the trees and plants.” Her sound designer even recorded the game’s ambient noise—crows, mourning doves, footsteps crunching through leaves—at the site itself.

The game caused some ripples when it came out—Smithsonian Magazine described it as “the world’s most improbable video game”—but to Fullerton, this misses the point. “I think it’s fairly ironic that one form of media is considered more incongruous than another when expressing ideas about nature,” she says. “Walden, the book, is a mediated account of Thoreau’s experiences in nature, in much the same way that Walden the game is a mediated account of the book itself … the game is just another form of media describing the pond.”

Playing also reminded me that the cathartic aspects of Walden have always been inextricable from more practical concerns. In the case of the game, these concerns are less cultural or scientific than personal: Fullerton has written that she made the game to inspire players to “find a balance between survival and the sublime.”

During my game-playing, this was tough to achieve. What with the planting of beans, the visits to family in Concord, and the constant search for Emerson’s lost books, there wasn’t enough time some days to go down to the virtual shore. When a warning screen popped up—“Soon Walden Woods will change to reflect the passing of seasons”—I laughed out loud. I wish I got a pop-up like that when summer was ending, to remind me to properly enjoy myself, to shut my laptop, and to spend more time at whatever Walden we have.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook