New Research Suggests Solar Storms Don’t Lead Whales Astray

Whatever is causing whales to strand themselves on shore, it’s likely a more complicated cocktail of factors.

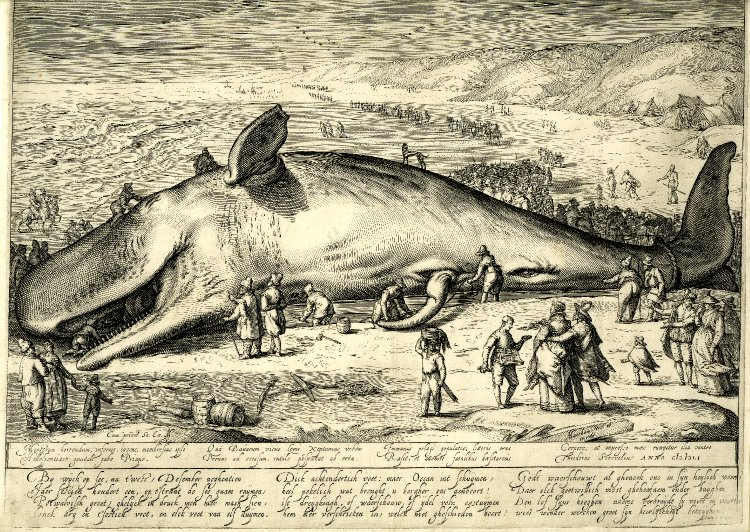

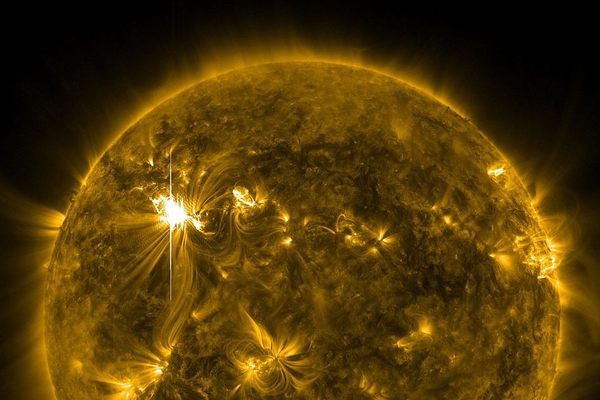

For hundreds of years, people have been documenting whales and dolphins stranded on shore, but no one has ever understood why it happens. One of the most intriguing explanations is that space weather—magnetic storms initiated in the Sun, that sweep across the solar system to Earth—might be messing with cetaceans’ navigational tools and causing them to lose their way.

Earlier this year, the physicist Klaus Heinrich Vanselow made a compelling case that, in the North Sea, at least, sperm whale strandings could be associated with solar storms. Now, though, new research suggests that space weather is not the cause of strandings more generally.

NASA began this research in partnership with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, and the original aim was to explore the possible connection between solar storms and whale strandings. They paired NASA’s space weather data with IFAW’s database of cetacean strandings, but they were not able to find a causal connection between the two. According to Antti Pulkkinen, NASA’s lead researcher on this project, “there is no smoking gun indicating space weather is the primary driver.”

That doesn’t mean space weather plays no role in cetacean strandings. “For strandings on many places on Earth it might not be the primary cause,” Vanselow says in an e-mail. He still believes that in the North Sea, for instance, it may contribute more to strandings than in other parts of the world.

But this new research suggests that, as a rule, other factors must contribute and likely play a larger role. The team responsible for this new finding is now planning to expand its analysis to other sets of oceanographic data, in hopes of parsing out more possible causes—tides, winds, temperatures, changing migration habits, the chemical content of the water.

Most likely, there’s no one cause for animal beachings, but it’s possible that by understanding the contributing factors scientists could better predict when they might happen. Better forecasting would help groups like IFAW prepare to help guide whales away from beaches—or direct them back to the water if they get stuck.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook