Eat Like an English Peasant With This Medieval Cookbook

It makes peasant food pleasant.

King Henry I’s only legitimate son, William, drunkenly drowned in the English Channel in 1120, leaving the throne heirless. When Henry I died 15 years later, civil war erupted. The period known as The Anarchy witnessed mass torture, extortion, and rebellion across the countryside. Susan Jones, of the living history group Iron Shepherds, calls it “an interesting time for foodies.”

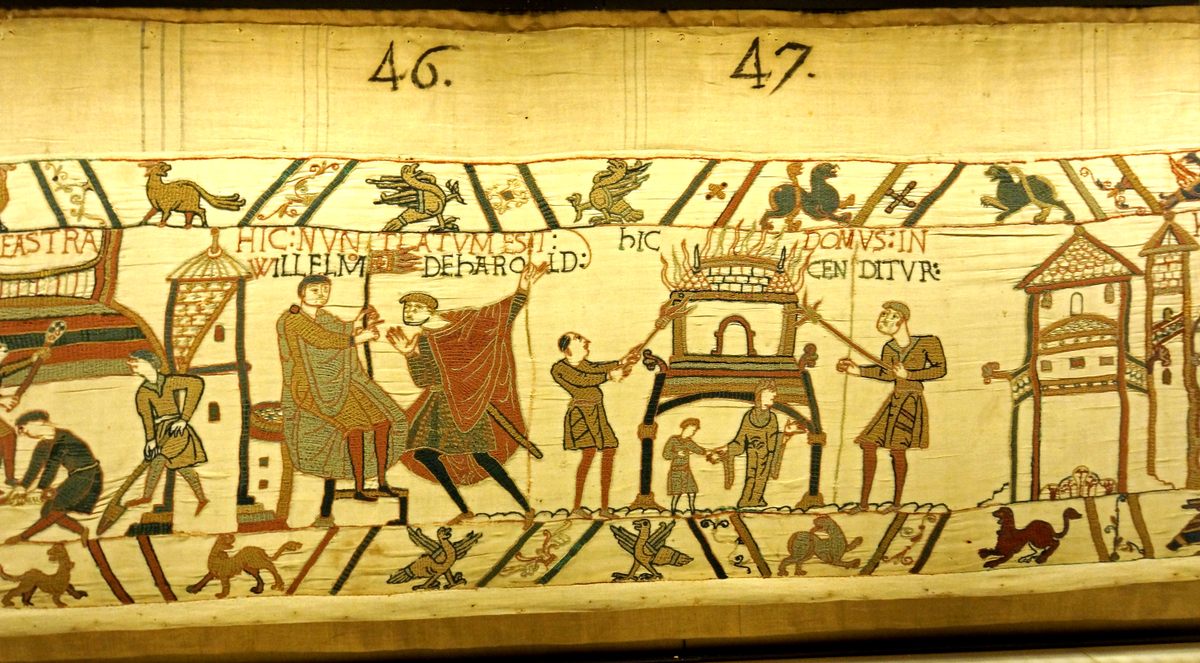

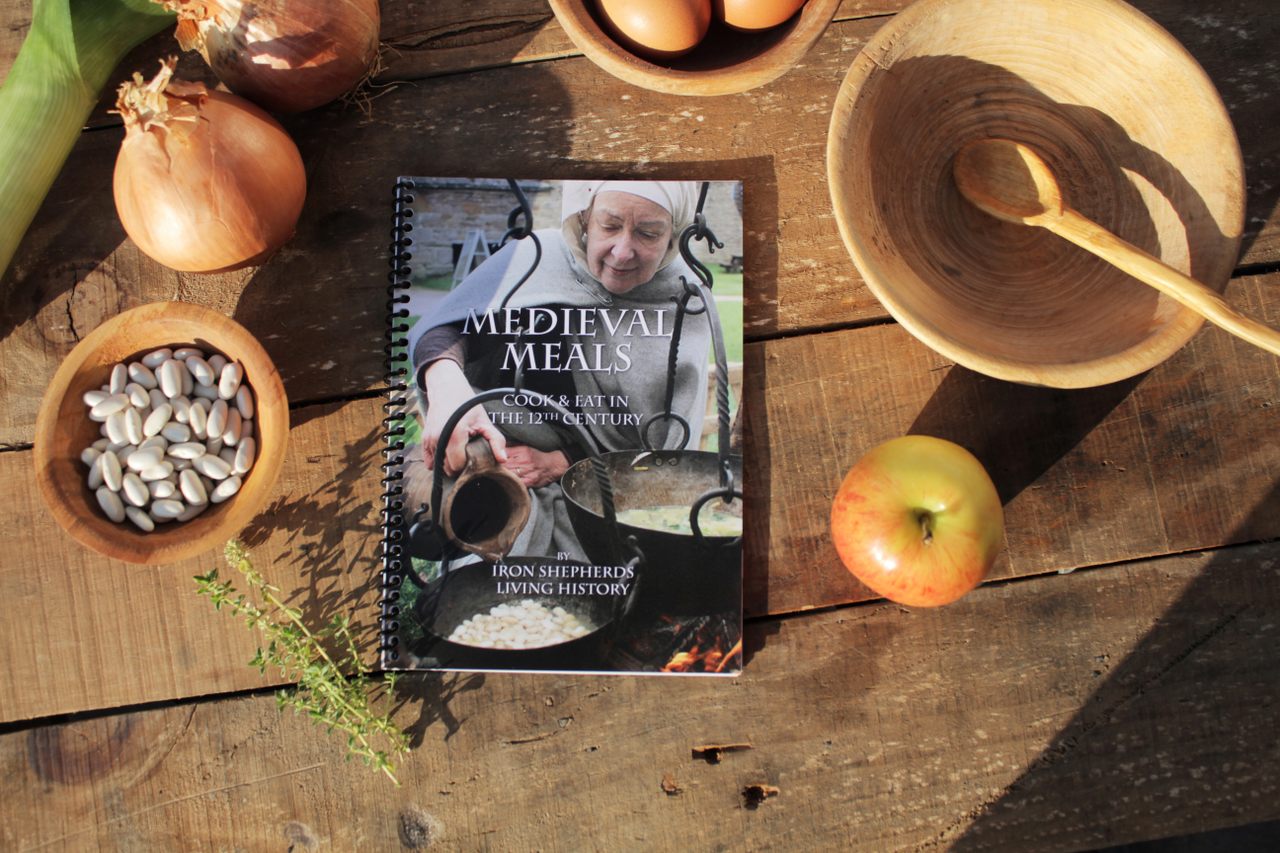

Iron Shepherds’ Medieval Meals: Cook & Eat in the 12th Century features some of the oldest written recipes in the Western world, according to Jones, who co-authored the book. The non-profit, volunteer group showcases how commoners lived, and ate, in their home county of Cumbria, in the North of England, while the country became embroiled in a bloody civil war shortly after the Norman Conquest. Chairman Stuart Appley adds that their region was, at the time, home to cultures ranging from the invading Flemish and Frenchmen to Celts and even Norse Vikings. Their thoroughly researched cookbook is a rare snapshot of the resilience of peasant kitchens during a transformative moment in England’s history.

As such, the dishes exclusively feature ingredients present in 12th-century kitchens. A recipe for barley bread calls for honey and ale, while a one-pot rabbit stew employs a simple mélange of herbs and leeks. As lead writer, Jones sourced most of the recipes from medieval art, literature, and manuscripts, as well as experimental cooking done with period ingredients over an open fire with suspended pots and spits. For Jones, however, it’s less about the food than the history behind it.

Cumbria’s unique situation during the chaotic century is the Iron Shepherds raison d’être. Preemptively handed over to Scotland (“no doubt a way to keep the Scots from causing problems while The Anarchy raged on,” says Appley), the region was spared much of the chaos. The lives of these fortunate few are celebrated by the group, whose displays of turning bowls on a pole lathe, knitting large fishing nets, and, of course, cooking, are a testament to early Cumbrians adapting to an England in transition.

Cumbria’s peasants, it turns out, ate much as we strive to today—though for vastly different reasons. Lack of access to an international array of foods meant the peasants’ diets consisted of plant-based, low-sugar meals of locally sourced, if not home-grown ingredients; the book’s simple “Roast Onions with Thyme” recipe is emblematic. Voluntary, intermittent fasting wasn’t uncommon either, says Jones, albeit in the name of religious self-discipline rather than detoxification. An excerpt from a contemporary work by Bishop Grosseteste indicates that table manners were to be observed (“Never eat bread with abandon till they have set down the dishes. People may think you are famished“). An aside on at-home cooking describes a “home-delivery system” that catered to the many families who, rather than couch-laden, had no kitchens whatsoever.

Elsewhere, Medieval Meals highlights the religious and culinary boundaries that shaped the peasants’ diets and made them so different from our own. A recipe for Monastic Beans with pork lard is a reference to the Rule of St. Benedict. With beans so easy to grow and hard to spoil, writes Appley, monks were prescribed a pound daily alongside a pound of bread—much to the recorded chagrin of many in the monastery. Peasants outside the clergy, whose days “started off with bread and ale,” fared little better. God’s animals were spared slaughter four days a week in reverence of Noah’s Ark, although Medieval Meals nods to a conveniently flexible, if not altogether bizarre, medieval interpretation of meat: “Fish didn’t count as meat … and beavers were eaten because of the superficial resemblance of the tail to fish.”

Anarchy aside, Jones points out that the 12th century in England was one of culinary evolution. Returning crusaders introduced exotic berries, citruses, and spices from the Middle East, evinced in the book’s recipe for Tardpolene, a baked fruit pastry of pears, cinnamon, and raspberries. The northward Norman expansion, says Jones, also brought the terms “beef” and “mutton” into the English language, while introducing early forks to the previously spoon-centric English table.

Hidden in this tumultuous century that the Iron Shepherds so diligently showcase is a resilient society surviving and thriving despite limited supplies and strict religious dietary dogma. Moving through the book from simpler breads and beans to richer stews and fruit-laden sweets, one gets the sense of a weight being lifted; of long-absent fathers returning home with strange spices and fruits; and of a people, against all odds, well-fed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook