Easter Island’s Monoliths Made the Crops Grow

By quarrying rock for the statues, the people of Rapa Nui fertilized the soil.

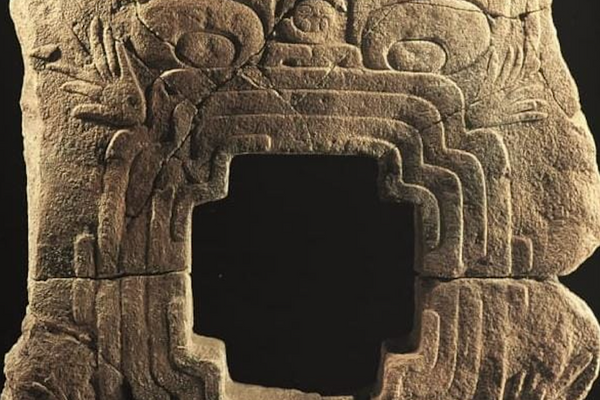

When Europeans first reached Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, on Easter Day, 1722, they were awed to find around 1,000 imposing stone moai, or monoliths, carved in the shape of human beings. The statues overlooked a barren landscape. While archaeological evidence shows that Rapa Nui was once lushly forested, by the time Europeans reached the island, it had been clear-cut, devastated by human overuse, ecological change, or a bloody civil war. The population, which had once likely numbered in the tens of thousands, had been reduced to 3,000 at most.

For the Dutch sailors, many of whom had travelled Polynesia extensively, the sculptures were astounding. Human sculptures are rare in Polynesian art, which more commonly depicts mythic and animal forms. In addition, Easter Island was incredibly remote—more than 1,200 miles away from other populated islands, and 2,100 miles away from Chile, to which it now belongs—and appeared barren. According to Joanne Van Tilburg, a UCLA archaeologist who has researched Easter Island for decades, the sailors regarded the sculptures as a mystery. “How and why did people produce these wonderful sculptures when it was crystal clear that the environment of the island had been completely altered?” she says.

The Dutch, of course, weren’t the first sailors to land at Rapa Nui. That honor goes to the Polynesian seafarers who settled the island by around 1200. While the island likely had significant vegetation, including forests, when they arrived, a 63-square-mile chunk of rock in the middle of vast ocean is an unlikely incubator of a complex society. But the Rapa Nui people initially thrived, producing Polynesia’s only writing system and the famous monoliths.

When Europeans visited Rapa Nui in the 1700s, however, the island’s population was already in decline, and its history getting hazy. The ship’s officers recorded their observations, but the most extensive documentation of the Islanders’ views of their own culture didn’t emerge until 1914, when an English anthropologist, Katherine Routledge, teamed up with a Rapa Nui man, Juana Rapano, to collect oral histories. By that time, after almost 200 years of Peruvian slave raids, missionary activity, and European disease, many memories of precolonial society—including knowledge of the island’s writing system, which died with the elites who mastered it— had been lost.

This has challenged archaeologists who study the monoliths. They have long theorized that the monoliths represented family lineage and prosperity, meanings they continue to carry for contemporary people. But they had little concrete proof.

A recent study by Van Tilburg and her archaeological team has helped fill in these gaps. By testing the soil of the area where moai rock was quarried, they found evidence that the statues not only symbolized prosperity, but that the very creation of the moai contributed to agricultural abundance.

Van Tilburg’s team has spent the past five years excavating Rano Raraku, a quarry in the island’s center whose rock accounts for 95 percent of the moai. The team was analyzing statues found in the area when geoarchaeologist Sarah Sherwood, more out of habit than anything else, tested the local soil. “When we got the chemistry results back, I did a double take,” Sherwood told UCLA’s Newsroom.

The team expected the quarry to just be a quarry. Instead, the analysis suggested that sweet potatoes and bananas had grown nearby, in soil rich in calcium and phosphorous. On an island with limited resources, where the rest of the soil had long since been depleted, the presence of such fertile soil was stunning.

The tested soil contained high concentrations of rich clay that forms when lapilli tuff, the local bedrock, is exposed to the elements. As miners carried rock out, Van Tilburg and her team now believe, mineral fragments mixed with local soil, acting as a kind of fertilizer that turned land around the quarry into rich agricultural fields. Rano Raraku wasn’t, as previously believed, just a quarry. It was a prosperous agricultural area, where the moai’s ritual power became realized by the very act of their creation.

These findings also change our understanding of Rapa Nui’s history, which is often described, as in Jared Diamond’s bestseller Collapse, as a cautionary tale of rapacious environmental degradation. While it’s true that a dramatic shift happened before the Dutch arrival, which the Europeans exacerbated, these findings show that Rapa Nui’s people developed innovative ways to produce food with limited resources. For the locals on Van Tilburg’s team, the findings point to continuity and resilience, despite cultural and demographic rupture. “It did point to the fact that life went on in a very positive way well past the point where it was suggested that the environment couldn’t support a population,” Van Tilburg says.

While the island’s people, environment, and culture have endured dramatic changes over the years, the monoliths—weatherworn but steadfast—continue to bring abundance to Rapa Nui. “For contemporary people they’re related to prosperity,” says Van Tilburg. “The prosperity, in this case, is defined as tourism.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook