How ‘Shoebox Lunches’ Made Black Travel Possible During Jim Crow

Humble shoeboxes allowed African Americans to dine with dignity.

Youtube videos of celebrity sneaker-head closets often showcase massive square footage, multiple colorways on display, and not a box in sight. Your average hypebeast might wear new kicks a handful of times, then rebox and sell them for spring break plane fare. But for the mid-century African-American traveler, shoeboxes were culinary currency. During the age of Jim Crow, a sturdy shoebox with a meal inside could mean avoiding conflict or death.

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act became the law of the land. One function of the bill was to eliminate overt racism while traveling. Yet even after the bill went into effect, many food establishments kept forcing black customers to order chocolate ice cream parfaits from frumpy side windows, while twisted-lip atmospheres in roadside stores deterred black vacationers from buying penny candy. Public accommodations, such as hotels, could no longer refuse lodging to African-Americans, but certain tactics could deny individuals a place to stay.

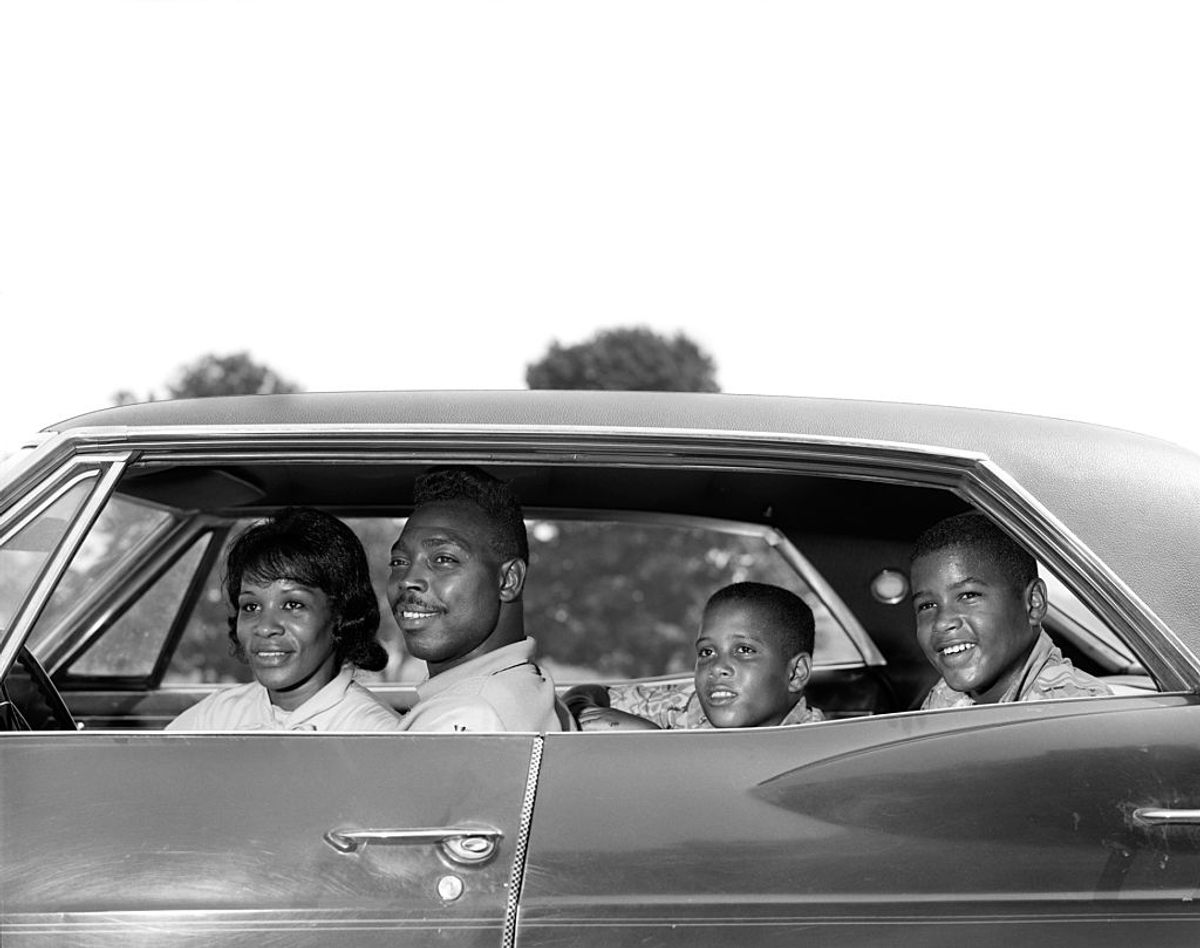

Pre-made meals not only reduced costs but served as your breakfast, if your route was void of sites listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book, a paper directory created by Victor Greene to guide black drivers and voyagers. “I remember my first travel experience to visit my grandmother. I was around four years old. We’d catch a train from Seattle, Washington, to Pine Bluff, Arkansas. We brought food on the train,” says Patricia Patton, a retired hospitality professional and entrepreneur. “In the 1960s, my family brought a car, and we’d drive from the Pacific Northwest to San Diego to visit family. The cooler would be packed with enough to eat for three days.”

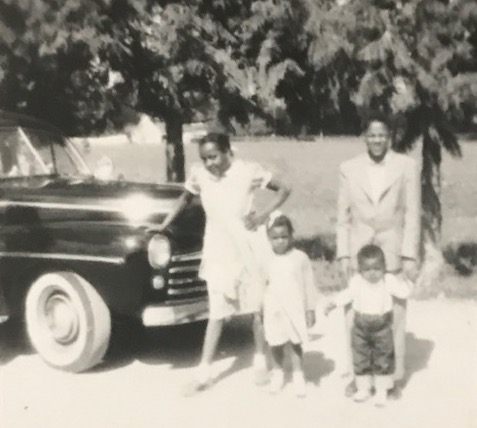

Many families started each trip by reminding kids of the rules—daylight bathroom pit stops only, and lunch served in the car. This extra caution was vital. “I was born in the late 1940s. I was not supposed to stare or look at people while traveling,” says Patton. “Often, my mother’s hand would tuck my forehead down, and no playfulness—we remained still to avoid any confrontation with white people.”

In Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America, author Candacy A. Taylor makes it clear that women were the powerhouses that made getting to and fro easier. A mother’s to-do list then was more than untangling iPad chargers and buying granola bars; it was icing down a cooler and twisting handkerchiefs containing pinches of salt and pepper. The matriarch’s job included repositioning the Stanley-type thermos, filled with water, from shifting on the floorboard.

When it was time to eat, Taylor notes, a “shoebox lunch” was set up, and most often, it was cold fried chicken pieces, thickly sliced country ham sandwiches, buttery pound cake chunks, and winter oranges or backyard peaches. The condiment-slathered sandwiches and an unbreakable platter for the perfectly piped deviled eggs would likely sit high up in the cooler to avoid spoilage.

Not everyone used an actual shoebox. Different vessels served the same purpose. Historical photos of the second Great Migration show black Americans in bus and train stations carrying metal lunch pails, slightly crumpled paper sacks, and packages tied with fabric or string. For individual leisure or business travel, the mode was always discretion, and dignity while consuming food was of utmost importance. A slice of layer cake doesn’t carry well and requires a utensil, but a wax paper-wrapped sweet potato pie slice doesn’t. Bologna sandwiches, fried pork chops, biscuits with homemade fig preserve, golden cornbread, teacakes, raisins, cheese, pickles, shelled pecans, peanuts, and apples are all portable foods that made an appearance on the laps of black passengers.

Though the era of the shoebox lunch has passed, they have become an emblem of resilience. One restaurant has even created replicas of the receptacle in tribute. Since 2017, the sleek, upscale soul food joint Beans & Cornbread in suburban Detroit has sold golden, perfectly seasoned chicken wings, cornbread, and your pick of two sides in a keepsake shoebox, with black history facts and illustrations lining the sides. Owner Patrick Coleman even sends the boxes to schools around the country as educational tools. “This year, we have shipped flat boxes to 34 states,” says Coleman.

Paired with hashtags such as #blacktravelmovement, hilarious Facebook threads on flying with miniature Hennessy bottles and Instagram stories documenting road trip eats are common. But many still pack food while traveling; it’s part nostalgia, part economics, and part logistics.

Omar Tate, a chef who writes about growing up in Philadelphia and unraveling his roots, left his steady culinary job in 2017 to retrace his southern lineage. His journey included several MegaBus legs. “The Savannah to Charleston bus ride is so beautiful, and most of the passengers are black,” he says. Coincidentally, his cousin recreated a shoebox lunch when packing him leftover chicken for his journey from North Carolina to Brooklyn. Not until he reflected did he realize this was a meaningful practice of the past. “I felt thankful for the freedom to experience traveling as a spiritual voyeur,” he says. “I felt protected every step of the way.”

This article was commissioned in partnership with the Museum of Food and Drink. MOFAD’s upcoming show African/American: Making the Nation’s Table is the first major exhibition on the culinary contributions of black Americans.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook