What Does the Title ‘Esquire’ Mean, Anyway?

And what does it have to do with lawyering?

The minor debate over First Lady Dr. Jill Biden’s title, which came up shortly after her husband’s election, may seem completely ridiculous and insulting, which it is, but it’s also the latest in a line of kerfuffles relating to how people in power in the United States present themselves. The extensive intricacies of British titling, and the power those titles conferred (and to a lesser extent, still confer), have left a lasting residue in some of the empire’s former colonies.

Those who think Dr. Biden should not use her earned title suggest she simply go by “Mrs.,” which signifies only that she is married, or “Madam,” which signifies only gender. The unstated goal of all this talk is a gross collection of sexism, elite gatekeeping, anti-elitism in general, and a simple partisan attack on the Biden administration. The idea of attacking someone in power by attacking a title is not a new phenomenon, and “Dr.” is not the only target.

One of the weirder movements in modern American political action attempted to attack a title so vigorously that it would have essentially collapsed the entire history of the American government. The movement didn’t succeed, because it was both factually wrong and wildly misguided, but it was wrong in a really interesting way. It relied on the title “Esquire,” which is one of the more common but most unusual ways a person can ask to be addressed.

That movement, born from the right-wing conspiracy forums of the early internet, purported that there was a “missing” Thirteenth Amendment that would have made the current Thirteenth (which abolished slavery) actually the Fourteenth. This phantom amendment, called the Titles of Nobility Amendment, was written in 1810. By law then, and now, the American government cannot bestow titles of nobility in the way that the English government once named new dukes or barons. The brief text of the amendment would have made these existing prohibitions even stronger: Any American who accepted a title of nobility or honor from a foreign government would be forbidden to hold office, and would be stripped of citizenship.

In 1983, a conspiracy theorist and researcher named David Dodge found an 1825 copy of the U.S. Constitution in the Belfast Library in Maine. The copy included that Thirteenth Amendment, and Dodge wrote several articles about it that made some rather assumptive leaps. Those leaps were: 1) The amendment had been legally enacted. 2) “Esquire” is a title of nobility. 3) “Esquire” also refers to lawyers. 4) The amendment rescinds the citizenship and the right to hold office from anyone with a title of nobility. Therefore, no lawyers have, since 1810, been allowed to serve in government or even hold citizenship. Therefore, given that over half of the country’s presidents and a huge percentage of its elected officials have been lawyers, everything you thought about this country’s history is a gigantic sham. At least that’s what Dodge argued.

It amounted to a huge attack on perceived elitism, and has been wielded repeatedly, though never effectively, as a weapon against Democrats. In 2010, the Republican party of Iowa attempted to include recognizing the missing Thirteenth Amendment as part of its platform, meant in this case to remove then–President Obama from office. Obama did pass the Illinois bar exam, making him a lawyer, and had also received a Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, which would, if you follow the odd logic to its totally illogical conclusion, have disqualified him for the office of president. There’s something of a libertarian and populist bent to it.

Jol A. Silversmith, a lawyer who works primarily with aviation law, took a side interest in this whole conspiracy business when he was in law school. “The right-wing groups are factually wrong, but did latch onto the fact that this was a very poorly documented amendment,” he says. Silversmith wrote a definitive article on it in the Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal in 1999, debunking just about everything in the conspiracy theory. For one thing, the amendment was never ratified by enough of the states to be enacted. It was printed in some legal texts as though it had been ratified, but Silversmith writes that, due to a chaotic government (dealing with both new states and new wars) and poor communication infrastructure, there were frequent misprintings and uncertainty about what exactly was and was not in the Constitution.

The other fascinating part of this whole saga is the assertion that “Esquire” is a term of nobility in the first place, and its one-to-one connection with the legal profession. When we talk about “titles of nobility,” the sort that the failed Thirteenth Amendment was trying to block, we’re talking about titles conferred on a person by a government, not by trade.

The term “Esquire” comes to the United States from medieval Europe, and more directly from the United Kingdom, a place absolutely mad for nobility and titles, though admittedly less now than it used to be. The governments of the countries that make up the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) have the power to confer a wide variety of titles on their subjects. And there’s a pretty wide variety of ways the United Kingdom and its imperial predecessors could bestow these signs of nobility. The peerage system creates an aristocratic network of families outside the royal family; those might, at different points in history, come with an obligation to supply military forces to the king, or with a seat in government. Titles in the peerage system include duke, marquess, earl, viscount, and baron. They are historically passed down to future generations, as fans of Bridgerton or Downton Abbey well know.

Go down a level and you get to those who have lesser titles granted by the government, generally referred to as “Sir” or “Dame.” There are the baronets, who are kind of a weird outlier, given that they’re referred to as “Sir” as well, but also pass that title to eldest sons. They’re the gibbons of the aristocracy—not really a great ape like the chimpanzee, but certainly not a monkey.

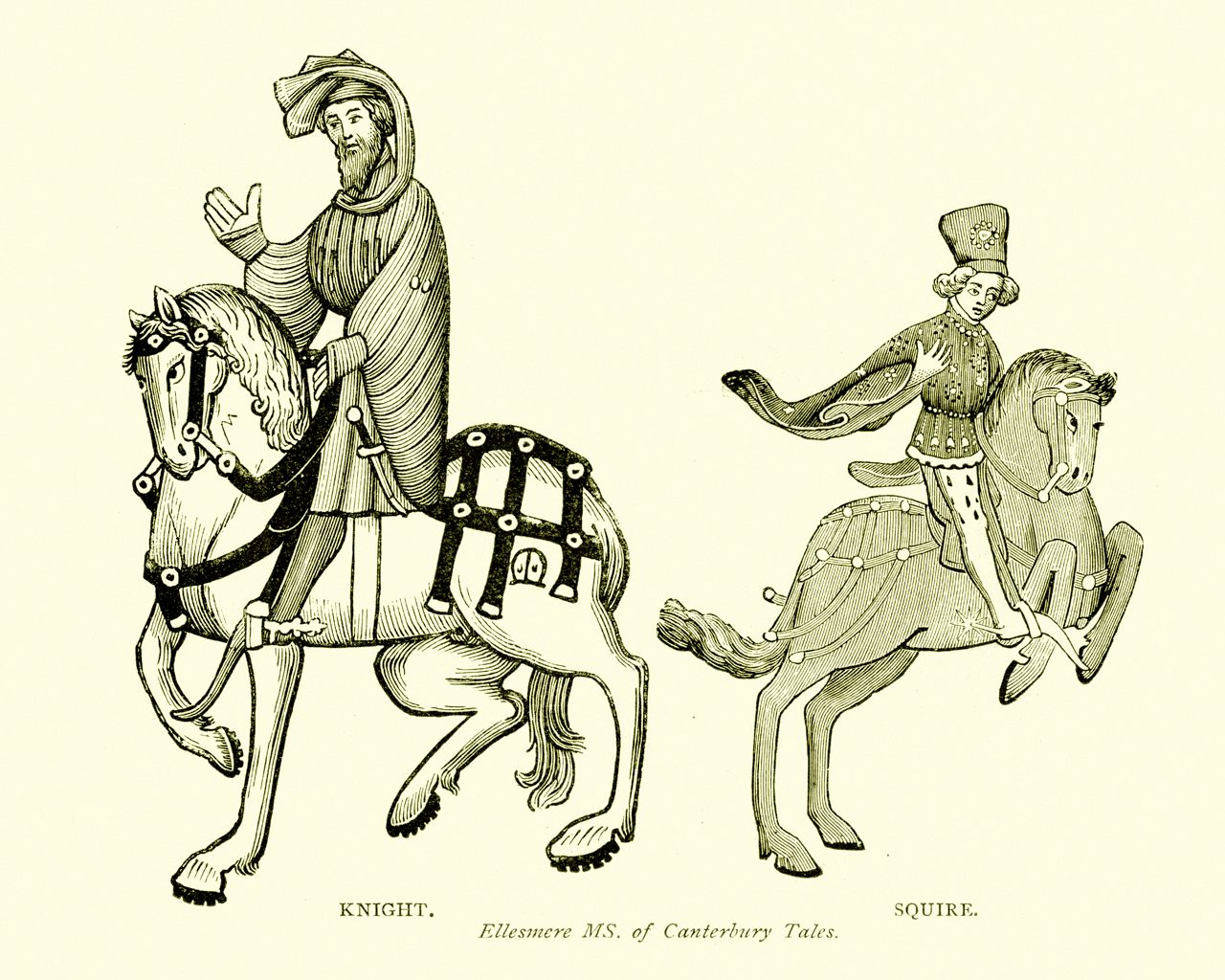

Another step down is the knights. Prior to around 1000, the word “knight,” or its equivalents such as knægt, kneht, and cniht, had no noble connotation; it just referred to a professional soldier. The best of those soldiers were sometimes given land or money by lords, and slowly they began to enter noble society. If a lord wanted to hire a bunch of mercenaries to defend or attack or invade, knights could provide that, at a cost. Eventually the social distinction between the two was fairly slim. Knights, after all, had to be wealthy and command their own soldiers.

During the Crusades, as roving bands of knights became a social problem, the Catholic Church embarked on a quest to set up some kind of social restraint through a chivalric code. It worked, kind of. Knights weren’t restrained, exactly, but some did acquire wealth and social status. During the 13th century, the role and position of knighthood really changed as the ideal of chivalry took hold. Knights became an elevated class of their own.

This is where esquires come into play. The word itself derives from Old French, and in turn from Latin, where it means something like “shield-holder.” In the 1200s and 1300s in England, a variety of languages were used, so such figures might be referred to as the Latin armiger (“arms-holder,”) or scutifer (“shield-bearer”), or the French escuier, which became “esquire.” These terms all refer to roughly similar people. This role was generally considered moderately prestigious for young men of some wealth, but at its core it was a service job. You carry a knight’s stuff, tend to his horses, that kind of thing. “Esquire” and “squire” were names for the same gig for a few hundred years.

In 1363, the esquire’s place as a respectable social rank was codified in the Sumptuary Laws, which were essentially a huge list of what different groups of people could and could not wear. That list included esquires as a social group, alongside gentlemen and anyone else below the level of knight who actually had money and land. This was the same time that the idea of a gentry emerged in England: People who are not noble, but certainly not peasants, either. They were people worthy of being ranked above somebody in the social hierarchy.

So esquire had come to suggest moderate respectability with a dash of prestigious servitude. By the 1500s, knighthood no longer necessarily had any connection to soldiering and had begun to be used simply as an honorific, a nice title a sovereign could hand out to pals. A similar process occurred for esquire, and divorced it from its roots. By 1586, a writer named John Ferne had already described the term as basically meaningless and kind of annoying, used by rich guys who wanted to seem noble-adjacent.

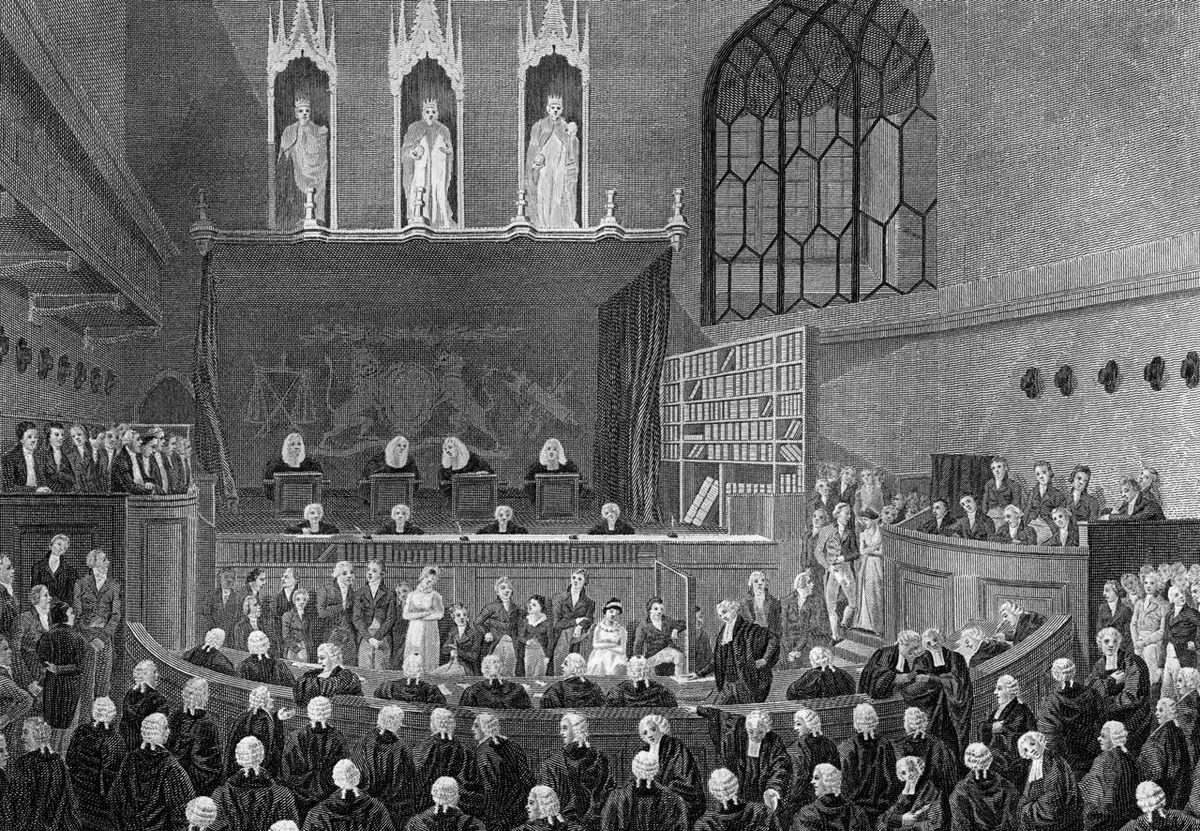

Successive writers tried to pin down what it actually meant, with no great success. Ferne, who was himself also a lawyer, noted that it was often used by those in the legal profession. Later definitions suggest someone adjacent to power, maybe the son of a knight or the younger son of a titled noble who would receive no other title of his own. But also, consistently, it included someone in a legal profession: a justice of the peace, a barrister, a sergeant-at-law. It was never recorded, explicitly, why this might be.

“Esquire” soon migrated across the Atlantic. Virginia’s Colonial Council, which held meetings just before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, used a variety of noble-sounding but not actually noble titles for its members, including “The Honourable” and, of course, “Esquire.” It also continued to be used for law-adjacent Americans; such as a justice-of-the-peace esquire from 1797.

Over the following two centuries, “Esquire” began to fade in the United Kingdom. In the 20th century, the country slowed and then stopped giving out hereditary titles; the last one granted was in 1990.* Social changes—immigration, new forms of wealth besides land ownership, fame and adulation going to entertainers and athletes instead of merely the obscenely wealthy—left the aristocracy intact, and rich as hell, but no longer at the forefront of social consciousness. “Esquire,” as it had become a term of straining toward nobility, became less useful.

In the United States, though, it persisted, specifically in its connection with the legal profession. This profession is largely state-regulated, and most states don’t really care about the use of the term by people in or out of the profession. Some states have penalized people for it, though. In California, Arizona, and the District of Columbia, local bar associations have penalized or advised against any non-lawyer (or suspended lawyer) from appending “Esquire” to their names, as it may erroneously signal the capacity to practice law.

American lawyers all could call themselves “Esquire,” inasmuch as anyone can, and for lawyers it wouldn’t be misleading. But not many do. “There’s not a huge amount of debate, but when it does come up, there’s a sense that this is a kind of archaic term, it’s somewhat embarrassing,” says Silversmith. “It’s something where, in my personal experience, I would never use it. It would be horrifically pretentious to do that.”

But lawyers, unlike doctors (medical or otherwise), have no other title-based way to signal what they do, or, to be somewhat uncharitable, that what they do is special, and therefore that who they are is important. Lawyers are simply not conferred a title when they pass the bar. “Esquire” steps in there, but the very fact that it is optional conveys a sense of self-marketing that many lawyers may find unbecoming. That sense, though, is perfectly in line with how the term has always been used.

Despite all these facts—that “Esquire” is not a title of nobility, that it does not necessarily refer to lawyers, and that the “missing” Thirteenth Amendment was never ratified in the first place—the anti-authoritarian cause still pops up from time to time. It is an early populist meme of the internet age, one that took root in message boards and forums, picking up some minor momentum despite being both impractical and wrong. Today, of course, when the power of these memes actually invaded the halls of American power, the arguments of the Thirteenthers seem almost quaint.

* Correction: This article originally stated that the last hereditary title was granted in 1984. Another title was given, to Sir Denis Thatcher, husband of Margaret Thatcher, in 1990.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook